In Nazi Germany, work was shaped and defined by the fascist fixation with order, hierarchy and service to the state. In a typical fascist society, the needs of the nation are paramount; there is little or no concern for the petty interests of individuals. Consequently, there is no support for concepts like trade unions or workers’ rights and freedoms. Any concern with these things would imply that the individual must be protected from the state, rather than contributing to it. This fascist attitude to work was also reflected in Nazi labour policies, workplace organisation and propaganda. Nazism was very much focused on surrendering individual interests to those of the party and the nation. As a consequence, the Nazi regime radically changed the organisation of labour within Germany, particularly in the fields of heavy industry and military production.

The NSDAP’s first major labour policy was to ban trade unions (May 2nd 1933). To establish control of German labour, Hitler also established the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (the DAF or German Labour Front). The DAF was, in effect, a government-run union. DAF membership was compulsory for employment in most occupations. DAF members belonged to one of 20 ‘worker ranks’ and paid weekly membership dues, ranging from 15 Pfenning to 3 Reichmarks. These membership dues made the DAF a significant source of revenue. In 1934 it collected 300 million Reichmarks; by 1936 this amount had doubled. The DAF was led by Dr Robert Ley, a chemist by trade, a World War I veteran and a fanatical NSDAP member. Ley made grandiose promises to DAF members, telling them in 1933: “I myself am the son of a poor peasant … I swear to you we will not only keep everything which exists, we will build up the rights and protection of the workers even further”. Ley did initiate a few positive reforms to workers’ rights, like cracking down on bosses who dismissed employees for trivial reasons. But as the Nazis looked to increase economic production in the mid-1930s, the DAF began to trade off and surrender workers’ rights to increase productivity. This was hardly surprising since the DAF was effectively a branch of the Nazi government, not a true trade union. As historian Michael Thomsett explains: “The German worker was no longer represented by anyone. The [DAF’s] real job was to control German labour, not work for its good.”

“Workers in the Third Reich lost most of their freedoms and rights… with their unions gone, workers had no say in wages and conditions of employment, which were now regulated by the state. Despite the economic recovery, real wages never rose to what they had been in 1928. Taxes were high; the cost of many consumer goods such as clothing and beer increased… on the other hand, workers were not cast into a condition of deprivation. To some extent, workers were pacified by what the Nazi state did provide.”

Joseph Bendersky, historian

The year 1935 brought more concerted attacks on the rights of German workers. These measures were condoned, and in some cases actually initiated by the DAF. From February each German employee was required to keep a workbook, listing his or her skills and previous occupations. If a worker quit their job, their employer was entitled to retain their workbook; this made obtaining a new job almost impossible. From June 1935 Nazi-run agencies took over the management of work assignments, deciding who was employed where. Wages were set by employers in collaboration with DAF officials; workers could no longer bargain or negotiate for higher wages. The most telling reform was the removal of limitations on working hours. By the start of World War II (1939) many Germans were working between 10-12 hours per day, six days a week.

There was some opposition to this attack on workers’ rights. In 1936 a document called the ‘People’s Manifesto’ called for the removal of the Nazis and the restoration of pre-Nazi rights. The People’s Manifesto was an illegal document but was still circulated in some workplaces. Large factories were also infiltrated by communist agents, who attempted to whip up opposition to the Nazi regime. One group, led by Robert Uhrig, published and circulated anti-Nazi material in industrial factories around Berlin. After the outbreak of World War II these groups collected information about Nazi industrial and military production and smuggled it out of Germany to the Allies. But by and large, most Germans did not complain much about Nazi labour policies or the DAF. Most of them recalled the horrors of the Great Depression and were grateful to be working at all.

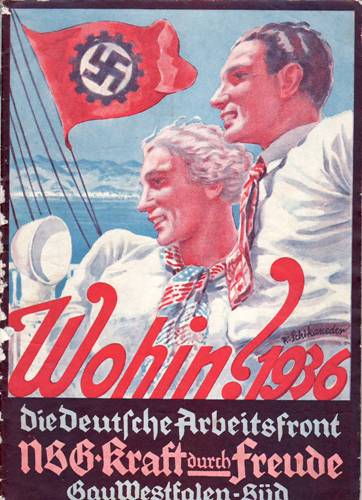

These propaganda devices extended into leisure time. In 1933 the DAF established Kraft durch Freude (‘Strength through Joy’), essentially a state-run holiday company. KDF encouraged hard work by offering cheap holidays and after-work activities. DAF leader Robert Ley ordered the construction of two new cruise liners to supply subsidised overseas holidays for German workers. A cruise to the Canary Islands, for example, would cost just 62 marks (around half the average monthly wage for unskilled factory workers). In reality, however, most of the places on these cruise ships were snapped up by NSDAP officials and members. Skiing holidays in the Bavarian Alps were offered for just 28 marks, while a fortnight-long holiday in Italy cost 155 marks. In 1938 alone, 180,000 Germans went on cruises to exotic locations like Madeira and the Norwegian fjords. Others were given free holidays within Germany. Kraft durch Freude also built sports facilities, paid for theatre visits and supported travelling musicians and entertainers. None of this came free: German workers paid for these benefits through their compulsory DAF deductions. But the image of German workers being given holidays and entertainment had significant propaganda value.

1. Nazi labour policy was largely based on fascist ideas. Fascism was concerned with order, hierarchy and the surrender of individual rights to national interests.

2. Trade unions were abolished by the Nazi regime in May 1933 and replaced by the German Labour Front or DAF, a gigantic state-run workers’ union headed by Dr Robert Ley.

3. In reality, the DAF did little to protect workers’ rights, wages or interests. Instead, as Nazi production quotas increased, the DAF allowed longer working hours and stricter controls on employment.

4. There was some opposition from workers and underground activists, who circulated anti-Nazi material, however, many workers remained grateful for the improved job security under the DAF.

5. The DAF also ran other agencies, Beauty of Work and Strength through Joy, that improved workplace conditions and subsidised cheap holidays for workers. While these benefited some workers, their main value was as propaganda for the Nazi regime.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Work in Nazi Germany”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/nazigermany/work-in-nazi-germany/.