The Nazi Party (NSDAP) was closely affiliated with and to a large extent defined by its paramilitary branches, the Sturmabteilung (SA) and the Schutzstaffel (SS). Each embodied the Nazi fascination with militarism, authoritarianism, order and discipline. They had their own uniforms, rank structures, awards and training regimes. Unlike the Reichswehr, however, troopers in the SA and SS swore loyalty to the party rather than to Germany. Their symbol was the notorious Hakenkreuz or swastika, an emblem of the party. They paraded at the forefront of party rallies in Nuremberg to demonstrate the discipline, organisation and strength through numbers of National Socialism. Yet there was much more to the SA and SS than snappy uniforms, goose-stepping and impressive ceremonies. These groups had a more sinister function. They served as the party’s muscle, dealing with political opponents through intimidation and violence.

Until the summer of 1934, the Sturmabteilung (SA) was the largest and most feared paramilitary branch of the NSDAP. The SA could trace its origins back to the first weeks of the party when fist-happy members were given free beer to provide security at meetings and rallies. The early SA was full of burly ex-soldiers, beer-hall brawlers, vicious Jew-haters and anti-communists – men who were nationalist and reactionary, but more interested in kicking heads than in staging a political debate. By September 1921, Hitler had fashioned these men into his own private army. He chose the name Sturmabteilung (‘Stormtroops’) and ordered they be outfitted in military-style uniforms. Party organisers acquired a bulk shipment of cheap army surplus brown shirts, which became the distinctive garb of the SA. Around 600 SA troopers backed Hitler when he attempted to overthrow the Bavarian government in November 1923. They were joined by an additional 1,500 SA men the following day, the small army marching alongside Hitler toward the centre of Munich. Of the 16 Nazis killed by police during the putsch, the vast majority were SA ‘Brownshirts’.

The SA was declared an illegal organisation in the wake of the Munich putsch. It did not disappear but reinvented itself as a new group called Frontbann and toning down its activities. On his release from prison in 1925, Hitler set about restructuring the SA by ordering the formation of new units. He appointed a new commander, Franz Pfeffer von Salomon. A former Freikorps officer, von Salomon had led terrorist raids against French troops occupying Germany’s Ruhr region in 1923. Through von Salomon, Hitler hoped to restrain the independent spirit that had grown in the ranks of the SA during his imprisonment. Hitler wanted a paramilitary force that could take control of the streets; he did not want the SA to become so powerful and independent it might take control of the party. Hitler expressed these concerns in a 1926 letter to von Salomon:

The formation of the SA does not follow a military standpoint, other than what is expedient to the Party. In so far as its members are trained physically, the emphasis should not be on military exercises but sporting activity. Boxing and ju-jitsu have always seemed more important to me than any bad, semi-training in shooting… What we need are not one or two hundred daring conspirators, but a hundred thousand fighters for our ideology. The work should be carried on not in secret, but in mighty mass processions. Not through daggers and poisons and pistols can the way be opened for National Socialism, but through the conquest of the streets. We have to teach Marxism that the future master of the streets is National Socialism, just as one day it will be the master of the State.

Many in the rank and file of the SA did not share this view. They saw the SA as a popular movement and a fast-growing revolutionary army, not just an obedient tool of Hitler and the NSDAP. This was not necessarily disloyalty but a difference of opinion about the role of the SA. There were also internal dissatisfactions within the SA about petty issues, such as pay and favouritism in promotions. Some were also unhappy that the NSDAP hierarchy had refused to allow more SA members to contest elections for Reichstag seats.

“The Reichswehr officer corps rightly regarded the Sturmabteilung as a pack of undisciplined and uncouth bums who had been responsible for a reign of violence on the streets unprecedented in the history of the nation, a period of crude brutality and terror in which even innocent people had been murdered in settlement of personal grudges under the guise of justified political activity.”

Trevor Ravenscroft, writer

Tensions between SA commanders and the party leadership came to a head in the lead-up to Reichstag elections in September 1930. Striving to present himself as a legitimate politician, Hitler ordered the SA to suspend its attacks on unionists, communists and Jews. This infuriated radicals in the SA, leading to an internal revolt in August 1930. Walter Stennes, a Berlin SA commander, presented Hitler with a set of demands, the most notable being that the party make three Reichstag seats available to SA members. Meanwhile, SA men loyal to Stennes ransacked several party offices. Hitler refused Stennes’ demands and sacked von Salomon for not foreseeing the revolt or handling it appropriately.

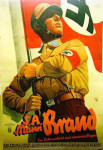

Confronted by a powerful SA that might move to overthrow him, Hitler assumed direct leadership of the organisation – but he had no interest in personally running the SA. For this, Hitler turned to one of his closest allies. Ernst Rohm was a World War I veteran who had stood alongside Hitler during the 1923 Munich putsch. After avoiding prison, Rohm travelled to South America to work as a military advisor. In September 1930, Hitler recalled him to take charge of the SA. Rohm was an experienced military commander and an inspirational leader of men – but he quickly deviated from Hitler’s instructions. Rohm had his own grand visions for the SA: he wanted to transform it from a disorganised group of street thugs into a citizens’ army that would one day replace the Reichswehr. He set about expanding the membership of the SA, with propaganda and vigorous recruiting (see picture). Rohm also engineered the takeover of other paramilitary organisations. In 1933, the SA assumed control of the Stahlhelm (‘Steel Helmet’) and the Kyffhauserbund (a war veterans’ association). Public servants, policemen and others deemed suitable came under significant pressure to join the SA.

By late 1933, the SA had around three million troopers and Rohm had been elevated to the Nazi ministry. The rapid growth of the SA was of great concern not just to Hitler but also the Reichswehr, which under the terms of the Versailles treaty was still legally limited to just 100,000 men. Rohm spelled out his intentions in an October 1933 letter: “I regard the Reichswehr now only as a training school for the German people. The conduct of war, and therefore of mobilisation as well, in the future is the task of the SA.”

1. The Sturmabteilung or SA began as the NSDAP’s security arm. Comprised mainly of ex-soldiers and street brawlers, the SA safeguarded Nazi meetings, broke up rival meetings and harassed opponents.

2. In 1921, the SA began to take a clearer shape as a paramilitary group. It adopted recruiting and training programs, a brown-shirted uniform, a rank structure and military-style insignia.

3. The SA continued to grow rapidly in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This led to differing views within the Nazi movement about what the SA was, what it should be and how it should serve Hitler and the party.

4. Hitler himself began to entertain concerns about the size and strength of the SA, as well as the attitudes and ambitions of its leadership. Officers in the German Reichswehr were also concerned.

5. In 1930, Hitler passed the leadership of the SA to Ernst Rohm, a long-serving ally and a veteran of the Munich putsch. Under Rohm’s command, the SA continued to grow, reaching a membership of around three million by late 1933.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Sturmabteilung – the SA”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/nazigermany/sturmabteilung-the-sa/.