Aware they would be arrested, investigated and dealt with by the Allies, scores of Nazi fugitives went into hiding or attempted to flee Europe. Evading capture was not difficult in the chaos and confusion of the end of the war. Western Europe was filled with refugees and displaced persons, former prisoners of war and demobilised soldiers. Nazi fugitives also benefited from support given by sympathisers across Europe. It would take years – and in some cases, decades – to locate these suspected war criminals and bring them to justice.

Avenues for flight

Allied investigations into Nazi war crimes started even before the end of the war and progressed quickly in 1945-46. The task of gathering evidence, processing hundreds of thousands of prisoners, interviewing victims and identifying potential suspects, however, was overwhelming. All but the most prominent Nazi fugitives were able to evade capture by dressing as civilians or enlisted soldiers, sometimes with forged or stolen identity documents.

Some Nazi fugitives who attempted to flee benefited from support networks, particularly in Italy and Franco’s Spain. Some were also assisted by a clique of German-Austrian priests within the Vatican. Several ‘ratlines’ (escape routes for Nazis) operated in these countries, allowing Nazi fugitives to move unmolested to ports such as Genoa and Cadiz.

Fugitives with adequate funds and false documents could buy passage and leave these ports for almost any destination around the world. Some ended up in the US, Canada, Africa, even Australia.

Most chose South America, however, where there was a healthy support network for fugitive Nazis. Argentina, in particular, became a haven for former Nazis. Its quasi-fascist dictator, Juan Peron, provided both informal protection and government support, offering several former Nazis Argentine citizenship and employment.

Adolf Eichmann

Nazi fugitives were investigated and hunted not just by the Allies and but the government of the newly formed Jewish state of Israel. Several Holocaust survivors, including Simon Wiesenthal, Tuviah Friedman and Elliot Welles, became ‘Nazi hunters’, gathering information and evidence about SS war criminals to locate and bring them to justice.

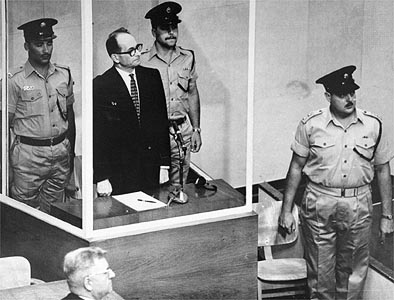

One of their highest-profile targets was Adolf Eichmann. A lieutenant-colonel in the SS, prior to the war Eichmann had been assigned to the Jewish Emigration Office, an agency responsible for assisting Jews to leave Nazi Germany. He helped draft a proposal called the ‘Madagascar Project’, which called for the entire Jewish population of Europe to be forcibly relocated to a large island off the east coast of Africa. Hitler approved this plan but it was never carried out.

In 1941 Eichmann was told of the Final Solution, the plan to exterminate of all European Jews. The following year, Eichmann attended the Wannsee Conference, where he recorded the minutes and resolutions of the meeting.

Eichmann’s flight and capture

Eichmann’s role in the Final Solution was mainly bureaucratic. He planned, organised and managed train systems that relocated Jews from their homeland or ghettos to the concentration camps. He carried out these duties with precision and cool detachment, with little concern that his work was responsible for the deaths of millions.

In 1945, Eichmann escaped via the ‘ratlines’ to Argentina, settling in Buenos Aires under the false name of Ricardo Klement. Strangely, his wife and children kept their own names, a decision that resulted in his detection.

Eichmann was kidnapped in 1960 by Israeli agents who smuggled him out of the country without the knowledge or cooperation of the Argentine government. Eichmann was put on trial in Israel, found guilty of war crimes and hanged in 1962.

Other notable fugitives

Klaus Barbie was a Gestapo captain who served in the French city of Lyon, where he personally assaulted, tortured and murdered hundreds of people, both Jews and members of the French Resistance. Barbie also organised the deportation of local Jews and is believed to have been responsible for the deaths of more than 14,000 people. Barbie fled to Bolivia after the war but was deported in 1983, aged 69. He was sentenced to life in prison, dying there in 1991.

Franz Stangl was an SS captain who served as commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka death camps. During his command, these camps murdered an estimated 300,000 people, mostly Jews. Stangl was arrested after the war but escaped to Syria via Italy, aided by a Catholic bishop. In 1951, Stangl relocated to Brazil, where he obtained work and lived unmolested under his own name. He was located and arrested in 1967 then deported to West Germany for trial. In October 1970 he was sentenced to life imprisonment, though he lived only another nine months.

Gustav Wagner was an SS sergeant who served at the Sobibor extermination camp, where he was notoriously brutal towards inmates. According to one report, Wagner would snatch Jewish babies from their mothers’ arms and literally tear them to pieces. Wagner escaped to Brazil after the war, obtaining work and citizenship there. He was identified and arrested in 1978 but requests for his deportation were refused by the Brazilian government. He died in 1980, aged 69, probably murdered.

Josef Schwammberger was an SS lieutenant given responsibility for several labour camps and Jewish ghettos in southern Poland, mostly around Krakow. Schwammberger was known for his ruthlessness and brutal tantrums, which invariably ended with prisoners being shot in numbers. Schwammberger evaded capture after the war and, in 1948, relocated to Argentina. He was located, arrested and identified in the late 1980s after the West German government posted a large reward. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1992 and died in custody in 2004.

Josef Mengele

Despite the sustained efforts of Nazi hunters in Israel and elsewhere, some Nazi fugitives continued to elude location and capture. One of the worst war criminals in history, Josef Mengele, was never brought to justice.

Mengele was an SS captain and a qualified doctor who was posted to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943. Only 32 years old, Mengele was given significant responsibilities there, including participating in selections on new arrivals, deciding which would be used for labour and which would be sent for extermination.

Mengele’s most horrific crimes, however, were medical and anatomical experiments he performed on camp inmates: dissections, vivisections, amputations, castrations, blood transfusions, forced conceptions and caesarian births, all conducted without anaesthetic or pain relief. Mengele had a special interest in twins, once sewing one pair of twins together to make conjoined or ‘Siamese’ twins.

Mengele went into hiding after the war, working as a farmhand until 1949 then fleeing to Argentina via Italy. He prospered there until 1955, working first as a labourer before returning to medical practice (though he had to do so illegally). He also divorced his wife and remarried.

Mengle moved in the same social circles as several other Nazi fugitives, including Adolf Eichmann. During Eichmann’s arrest and kidnapping in 1960, Mengele was spotted by Mossad agents, who reported his whereabouts to Nazi hunters.

Spooked by Eichmann’s capture, Mengele obtained documentation and relocated to Paraguay, then Brazil, where he died in 1979 while swimming in the ocean. His body was exhumed and positively identified in 1985. According to Mengele’s letters and anecdotal accounts, he remained a loyal Nazi until his death, firmly believing that he had done nothing wrong.

Operation Paperclip

Not all former Nazis were subject to arrest or trial. Both the United States and Soviet Russia rounded up and recruited German specialists, many of whom were SS officers, Nazi Party members or sympathisers, in order to deny the other of their expertise.

The US was particularly active in this regard. In mid-1945, Washington launched Operation Paperclip, a large campaign to gather information on Nazi scientists, technicians and engineers. Several of these specialists were located and moved to US-occupied Germany, out of Soviet reach.

Of particular interest to the Americans were the men who had worked on Hitler’s V-2 program, unmanned rockets that were used to launch deadly attacks on Britain in the final two years of the war. Washington coveted their expertise and hoped to harness it in their own ballistic missile program.

Some of these men had been implicated in or accused of war crimes. Hubertus Strughold was a medical expert recruited as part of Operation Paperclip, who became an important contributor to America’s space program. It later emerged that he was probably involved in human experimentation while stationed at Dachau. The Americans also recruited former Nazis as agents, such as Wehrmacht general Reinhard Gehlen, who would later set up a 4,000-man spy ring inside Soviet-occupied Europe.

“[Eichmann said] ‘I never found any pleasure in shooting to kill. I think the man who can look through the sights of his rifle into the eyes of a deer and then kill it is a man without a heart in his body. I thanked God that in the war I had not been made the actual instrument of killing anybody.’ Such was the magnitude of Eichmann’s self-delusion. He would continue to deny his role as an instrument of slaughter for the rest of his life. But for the time being, he had his own pelt to save. ‘I was the quarry now’, he acknowledged.”

Guy Walters, historian

1. Toward the end of the war, hundreds of Nazis attempted to flee Europe along so-called ‘ratlines’.

2. They were given assistance in this by pro-Nazi regimes in Spain and Italy, as well as other people and groups.

3. Many settled in the relative safety of South America, where support networks for fugitive Nazis existed.

4. One notorious escapee was SS doctor, Josef Mengele, who lived comfortably in South America until his death.

5. Not so lucky was Adolf Eichmann, who was tracked down, kidnapped, tried and executive by Israeli authorities.

Citation information

Title: “Nazi fugitives”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/nazi-fugitives/

Date published: August 20, 2020

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.