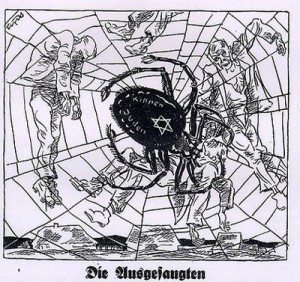

Nazi anti-Semitism was an intense form of the ‘Jew-hatred’ that infected German politics in the 1800s. Many nationalist politicians and pundits, particularly those who supported the unification of Europe’s German-speaking states, were exponents of anti-Jewish conspiracy theories. One was Wilhelm Marr, a nationalist writer who is credited with coining the term “anti-Semitism”. Marr was not the first German anti-Semite but he was certainly one of the most vocal. In a 1879 pamphlet, he claimed the newly-formed German state was at war with Jews living within its borders – and that one would not survive unless the other was destroyed. Other pamphleteers shared Marr’s beliefs, repeating stories of a mysterious Jewish conspiracy to sabotage the new nation. German-Jews served as a ready-made scapegoat for these ultra-nationalists. Almost any political failure could be attributed to the ‘international Jew’ and his unseen interference, despite a lack of evidence.

Anti-Semitic conspiracies persisted in Germany during and after World War I. Jews were regularly blamed for sabotaging the war effort – despite the fact that more than 100,000 Jews served in the German military during the conflict. The infamous Dolchstosslegende (or ‘stab in the back legend’) provided another avenue for anti-Semitism, nationalists and military veterans claiming that Germany’s surrender to the Allies in November 1918 was engineered by socialists and Jews within the government. This anti-Jewish scapegoatism continued to fester during the desperate 1920s. Most right-wing political groups of the Weimar era, such as the German National People’s Party (DNVP), harboured at least a small quota of anti-Semites or anti-Semitic ideas. For the most part, these groups kept their anti-Semitism in check. The DNVP, for example, restrained or expelled several of its most vociferous ‘Jew haters’.

There were, however, more radical parties where anti-Semitism was tolerated. One was the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP, or National Socialist German Workers’ Party – better known to history as the Nazi Party). The NSDAP sprung from humble beginnings, formed in 1919 as the Deutsche Arbeitpartei (DAP, or German Workers’ Party). Its founding members were insignificant men who all intense nationalists who accepted the Dolchstosselegend and other conspiracy theories, some of them with anti-Semitism at their core. The DAP’s few dozen members met each week to swill beer and curse the same targets: the new Weimar government, the Versailles treaty, other European nations and the alleged political, financial and cultural influence of Jews in Germany.

All this would have amounted to little if not for the arrival of a new member. In September 1919 Adolf Hitler, an army corporal, was sent to spy on the DAP – but while attending its meetings he became enthralled by the group’s political rhetoric. Through 1920 Hitler began to exert more influence over the DAP, chiefly through his passionate and forceful public speaking. The group reinvented itself as the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP, or National Socialist German Workers’ Party). It also achieved steady growth, attracting around 2,000 people to a rally in February 1920. By the end of the year, the NSDAP membership was 3,000 and growing. A sizeable proportion of these new members were hardline anti-Semites, drawn to the NSDAP by Hitler’s own obsession with Jewish conspiracy theories.

‘Rational anti-Semitism’

In 1920 the NSDAP issued, a 25-point manifesto, the first expression of its political platform. It summarised the NSDAP’s position on a range of issues, including government, economics and foreign policy – but it also contained two explicitly anti-Semitic points:

4. Only those who are our fellow countrymen can become citizens. Only those who have German blood, regardless of creed, can be our countrymen. Hence no Jew can be a countryman.”

24. We demand freedom for all religious faiths in the state, insofar as they do not endanger its existence or offend the moral and ethical sense of the Germanic race. The party represents a positive Christianity without binding itself to any particular confession. It fights against the Jewish materialist spirit within and without…”

Two vague mentions of Jews in a broad 25-point manifesto seems quite restrained, given the NSDAP’s reputation as a haven for embittered anti-Semites. This was a tactical move by Hitler and his inner circle. Hitler wanted the increase the NSDAP’s appeal to nationalists, monarchists, ex-soldiers, farmers and the urban middle class. To achieve this, the party had to present a relatively moderate front – while keeping its radical ‘Jew haters’ in check. Extreme rants or spontaneous violence against German Jews would alienate potential members, while placing the party at risk of police action. Hitler instead favoured what he called ‘rational anti-Semitism’. Action against the Jews, he argued, must be patient, planned and disciplined, rather than impulsive or populist. Taunting or attacking Jews would drive them underground, while frightening or alienating non-Jews. Hitler wanted Jews permanently extracted from German cultural and economic life; this could only be achieved with a prolonged campaign of public education, propaganda and legislation. He explained this view in 1919:

“Anti-Semitism based purely on emotion will find its ultimate expression in pogroms … but anti-Semitism based on reason must lead to the organised, legal campaign and removal of Jewish privileges. Its ultimate, unshakeable goal must be the elimination of the Jews.”

“One would naturally predict that the enthusiastic racists who shared Hitler’s rabid anti-Semitism would have joined the NSDAP quite early. Yet few of the top Nazi leaders were virulent anti-Semites before 1925. None of the more prominent men in the party joined it primarily because of anti-Semitism. This was true of Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, Hermann Goering, Hans Frank, the Strasser brothers, Baldur Shirach, Albert Speer, Gottfried Feder and Adolf Eichmann. Anti-Semitism became an issue of practical importance … only during the later 1920s… Many Nazi leaders simply accepted anti-Semitism as part of the baggage of Nazism.”

Sarah Ann Gordon, historian

1. Anti-Semitism was prevalent in Germany during the 19th century, perpetuated by nationalist politicians and writers.

2. Anti-Jewish conspiracies also flourished during and after World War I as Jews were blamed for Germany’s surrender.

3. Anti-Semites were well represented in post-war political groups, particularly those on the far Right like the NSDAP.

4. During the 1920s Hitler kept his anti-Semitic ideas in check, as he attempted to build a ‘respectable’ party.

5. Hitler preferred what he called ‘rational anti-Semitism’: a prolonged and organised campaign to extract Jews from German public life.

Citation information

Title: “Nazi anti-Semitism”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/nazi-anti-semitism/

Date published: July 28, 2019

Date accessed: April 20, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.