A horrific aspect of the Final Solution was the network of concentration camps operated by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945. These camps were constructed to house large populations of Jews and other minorities, for isolation, punishment or forced labour. By 1944, several of these camps had become dedicated extermination facilities.

Origins

The use of camps or compounds for detaining large numbers of civilians in one location was not a Nazi invention. The origins of concentration camps can, in fact, be found in the previous century.

Similar camps were used in the United States in the late 1800s to contain Native Americans. Spanish colonial rulers detained the local population of Cuba in concentration camps during the 1890s.

Concentration camps were notoriously used by the British army in South Africa during the Boer War (1899-1902) as an attempt to prevent civilians from hiding and supplying Afrikaner guerrillas. The death toll from disease and malnutrition in these British camps was significant.

Dachau

The Nazis began using concentration camps just weeks after coming to power. The first of these camps, in Dachau, near Munich, became operational in 1933.

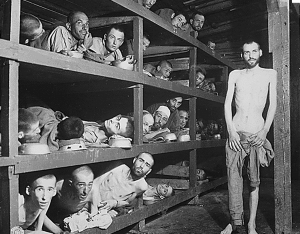

Dachau’s initial function was to contain political prisoners criminals, homosexuals and beggars. Prisoners at Dachau were housed in barracks on beds of straw and given meagre rations; they were forced to wear striped uniforms and a colour-coded system of badges that showed the reason for their internment.

Dachau contained relatively few Jews until Kristallnacht in November 1938, when around 10,000 Jewish men were rounded up and sent there. Jews eventually constituted around one-third of the 200,000 inmates who passed through Dachau’s gates.

Dachau was deemed a great success by Hitler and other members of the Nazi hierarchy. As a consequence, its facilities, organisation, arduous daily routine and reliance on forced labour were copied and employed in other Nazi concentration camps.

The Totenkopfverbende

During the war, all concentration camps were operated by a special SS division called the Totenkopfverbende or ‘Death’s Head Brigade’. Responsibility for the camps, their construction and management rested with SS leader Heinrich Himmler.

Until 1942, all concentration camps operated as Arbeitslager (labour camps). Their main function at this time was to house civilian prisoners for forced labour, usually on industries crucial to the war effort.

As the Nazis swarmed over more and more of Europe, they erected new camps, both in Germany and occupied countries. The larger Arbeitslager were sizeable installations, requiring a considerable amount of space, men and resources. The more significant camps housed several thousand prisoners, required a company of troopers and were overseen by a kommandant, usually an SS officer of Stuhrmfuhrer rank (captain or first lieutenant).

Daily routines

The daily routine of an Arbeitslager was carefully planned and rigorously enforced. Inmates performed forced labour daily, either within the camp or by marching to and from work sites. The hours of work were long: 10-14 hours per day, six or seven days a week.

Food rations for inmates were meagre, often just a lump of bread and some watery soup once a day. The lack of adequate fresh food meant that malnutrition and diseases like scurvy and dysentery were rife. Prisoners unfit for work were either left to starve, shot within the camp or deported en masse to the ‘death camps’.

Some labour camps also operated a number of smaller satellite camps, or ‘sub-camps’. The sub-camps allowed a small group of prisoners to be accommodated closer to their workplace – not for their benefit but to reduce travel and increase production time. Sub-camps were often administered privately by factory owners or civilian managers, aided by a small garrison of SS guards.

‘Annihilation through work’

From mid-1942, the function and operation of labour camps began to alter. As huge shipments of new workers, mostly Jews, regularly arrived from occupied Europe, camp commanders became less concerned with sustaining existing inmates.

Government correspondence from this time reveals a new policy called Vernichtung durch Arbeit, or ‘Annihilation through work’, mentioned by Hitler at an April 1942 meeting of camp commanders. With camp inmates now utterly expendable, camp commandants were given a free hand with regard to their treatment. Working hours were no longer mandated so prisoners were worked for unlimited periods of time; rest periods and food and drinks breaks were abolished.

Some camp commanders took the policy very seriously and introduced practices to intentionally kill off workers. At Mathausen-Gusen in Austria, prisoners were made to toil in a nearby quarry from dawn to dark, often in below-freezing temperatures. SS guards forced them to form queues and climb a 186-step staircase, each man carrying a heavy stone boulder. If one collapsed, the others below were struck by men and boulders like tumbling dominos.

Many prisoners were also compelled to work in industrial or chemical facilities with no protection against toxic fumes or dust. Others were forced to dig tunnels or underground bunkers in unstable ground. There was no regard whatsoever for the safety, wellbeing or survival of Jewish workers. As one former SS guard put it, “they were to be worked to death, sapped of every bit of their usefulness, then replaced”.

The death camps

The endorsement of the Final Solution in early 1942 also saw the construction of a new kind of concentration facility: the death camp. Like the Arbeitslagers, these camps supplied Jewish forced labour to nearby military or civilian plants – but their primary purpose was to exterminate large populations of ‘undesirables’ and dispose of their remains.

Six death camps were constructed in Poland: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sobibor, Treblinka, Madjanek, Chelmno and Belzec. European Jews earmarked for liquidation were shipped to these camps by railroad. The rail journey itself – two or three days in crowded boxcars, with no heating, sewage, food or water – claimed thousands of lives.

Once arrived, new inmates were subject to ‘selection’, where those fit for work were separated from those destined for immediate extermination. Sometimes this process was based on the robustness, health or fitness of the new arrivals. At other times it was quite arbitrary, perhaps determined by the whims of camp officers or directives for Berlin.

Those fit enough to complete work in the camp or at nearby factories were spared, at least temporarily. They were sent off to be washed, deloused and housed in crowded barracks. Those not selected for work were sent to their doom. Children, the sick and the elderly had negligible values as workers so were almost always gassed immediately. Some were selected for a worse fate: medical experimentation at the hands of SS doctors.

Exterminations

Jews and other inmates marked for extermination were stripped of personal belongings and had their hair shaved. They were then herded naked into concrete rooms resembling a large shower cubicle. The chamber was sealed tight and cyanide gas was pumped into it, killing hundreds of human beings in just a few minutes.

After a half-hour or so, the bodies were dragged out and moved into nearby crematoria, operated by other camp inmates. Corpses were incinerated at high temperatures in the crematoria, their tall brick chimneys depositing human ashes in and around the camp. Ash and bone fragments left after the burnings were carted away and dumped outside the camp.

This industrialised killing allowed the Nazis to extinguish human lives at a rate never before seen in human history. Working at full capacity, the Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp killed and incinerated more than 6,000 people a day. By the end of the war, the six death camps had disposed of more than 2.7 million people.

The Third Reich was dominated by camps. Camps were everywhere, in cities and the country-side, inside Germany and within newly conquered territory. Nazi leadership was irresistibly drawn to the camp as an instrument of discipline and control – and not just for opponents of the regime… They differed greatly in size, condition and function, but were united by a common aim to terrorise their inmates and intimidate the wider population. The extent of these camps is almost unfathomable: in the German state of Hessen alone, at least 606 camps have been counted; in the territory of occupied Poland, no fewer than 5,877.

Jane Caplan, historian

1. The concept of concentration camps was not developed by the Nazis. Large camps or compounds for concentrating civilians were used in the 19th century, such as in the Boer War.

2. The first Nazi concentration camps were built to contain and concentrate political prisoners. They were constructed and managed by a specialised division of the Schutzstaffel (SS).

3. After the Nazis occupied Europe, the Jews were herded into purpose-built labour camps (Arbeitslager). Later, Nazi commanders adopted a policy of ‘annihilation through work’.

4. Later in the war, the Nazis constructed and operated six special-purpose ‘death camps’, each within reach of Europe’s rail network. The best known of these was Auschwitz in southern Poland.

5. These death camps employed production-line methods for the murder and cremation of Jews, sometimes up to 6,000 people per day.

Citation information

Title: “The concentration camps”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/concentration-camps/

Date published: August 15, 2020

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.