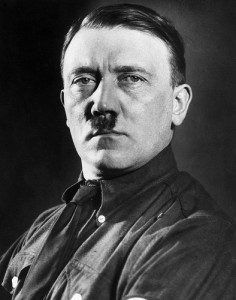

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) was the leader of the Nazi Party and chancellor and Fuhrer (supreme leader) of Germany between January 1933 and his death in 1945.

Early life

Hitler was born in 1889 in a small Austrian town near the German border, the youngest son of Alois, a petty bureaucrat with a violent temper, and Klara, a calm and gentle woman. Klara Hitler raised her children in the Catholic faith and as a boy, Adolf served as a chorister in his local cathedral.

Shortly before his 20th birthday, Hitler moved to Vienna, where he hoped to win acceptance into the city’s prestigious art academy. He was a competent rather than talented artist, however, so was twice rejected by the academy.

Instead of studying art as he had dreamed, Hitler spent the next four years on the streets of the Austrian capital. He was sometimes able to sell small portraits or colour postcards for a few coins; at other times, the future Nazi leader was so destitute he relied on soup kitchens and homeless shelters.

Anti-Semitism

It was during his miserable youth in Vienna that Hitler’s anti-Semitism intensified. The political atmosphere in the Austrian capital was a hotbed of anti-Semitism and dissatisfaction. Vienna had numerous anti-Semitic newspaper columnists and dozens of street-corner tub-thumpers who ranted and fumed about the “Jewish menace”. Like their German brothers, struggling Austrians found the Jews a ready scapegoat for their troubles.

This environment undoubtedly shaped Hitler’s views. He came to admire Austrian politicians who preached anti-Semitic ideas and slogans, particularly Georg von Schonerer and Karl Lueger. Jews were also active in the art community so were a convenient scapegoat for Hitler’s personal misfortunes.

Later, in his memoir Mein Kampf, Hitler described his life in Vienna as a time of misery – but also of revelation. “I ceased to be a weak-kneed cosmopolitan and became an anti-Semite … at this time of bitter struggle, the streets of Vienna had provided valuable instruction”.

War service

In 1913, Hitler crossed into Germany, mainly to escape compulsory military service in the Austrian army. Under threat of arrest and imprisonment, he returned to Austria to enlist in February 1914 but was rejected due to ill health. When World War I erupted in August 1914, Hitler was living in the southern German city of Munich and working as a house painter. He successfully petitioned the Bavarian king for permission to enlist there, despite not having German citizenship.

During his war service, Hitler became fascinated with and invigorated by military discipline, camaraderie and German nationalism. He served on the Western Front as a trench runner, risking his life constantly. He was wounded several times and won medals for bravery, including the prestigious Iron Cross.

In November 1918, as Hitler lay in hospital recovering from a gas attack, German generals agreed to an armistice that marked the end of the war. Hitler was devastated by Germany’s capitulation. He believed that a German victory was still achievable and that the country had been betrayed by ‘November criminals’: spineless politicians and communist infiltrators.

Like other nationalists, Hitler accepted as fact the Dolchstosselegend – the ‘stab in the back’ theory that attributed the German surrender to double-crossers. Again, Jews could be found at the heart of this conspiracy theory. Although 12,000 German Jews died in combat during World War I, nationalists claimed that Jews were opposed to the war and had undermined the German war effort. Jews were again a scapegoat, this time for the German defeat.

The Nazi Party

Hitler may well have remained another loud but ineffective anti-Semite had he not joined the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the DAP, or ‘German Workers Party’). When he attended one of its meetings in September 1919, the DAP was just a tiny fringe party with a membership of scarcely four dozen men. Hitler himself had been sent by the army to spy on the group and identify possible communists in its ranks. But instead of spying, Hitler was swept up in the DAP’s indignant political rhetoric and angry speeches – and began to deliver his own, something at which he excelled.

By 1920, Hitler was the DAP’s foremost orator. The topics of his speeches usually focused on the injustices of Versailles and the malevolent influence of Europe’s Jews. Over the coming months, the DAP’s membership grew rapidly, in part because of Hitler’s speech-making, and in July 1921 he became its leader.

In November 1923, Hitler’s party – by now called the National Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Partei (NSDAP, later dubbed the ‘Nazis’) staged an attempted coup in Munich. It was a dismal failure and Hitler was imprisoned for five years for treason, a lenient sentence passed by sympathetic judges. He served just nine months in Landsberg Prison.

Rise to power

On his release, Hitler decided to change tack and reinvent the NSDAP as a contender for seats in the Reichstag, Germany’s national assembly. Though he still despised democracy and parliamentary politics, Hitler believed they could be exploited to provide him with an avenue to power.

Hitler obtained this power on the back of the Great Depression and the despair it caused in Germany. As unemployment soared and conditions worsened, electoral support for the NSDAP increased. By July 1932, Hitler’s party was the largest in the Reichstag, holding 37 per cent of all seats.

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler was offered the chancellorship of Germany as part of a political deal. Within weeks, a fire in the Reichstag building in Berlin provided Hitler with an ideal pretext for dismantling German democracy and increasing his own power. Within six months of Nazi rule, Germany was a one-party totalitarian state with Hitler as its dictator.

Anti-Jewish policies

Hitler spent the next two years consolidating his power, dealing with rivals in his own party and expanding Nazi control over the state. The death of German President Paul von Hindenburg in August 1934 allowed Hitler to further increase his power by merging the offices of president and chancellor.

Hitler did take some early action against Germany’s Jews, most notably his April 1933 law expelling them from the public service. This was watered down after opposition from Hindenberg and others, however. By mid-1935, anti-Semites in the NSDAP were urging Hitler to take stronger action against the Jews. He responded by passing the Nuremberg Laws in September that year.

The Nuremberg Laws gave rise to a constant flow of anti-Semitic restrictions, prohibitions and legal revocations. Edict by edict, the Jews were expelled and excluded from the political, economic and cultural life of Germany. This anti-Jewish program escalated during 1938 when Jews were banned from practising medicine and law, attending state schools or owning businesses.

The culmination of this pre-war campaign against the Jews came in November 1938 with the unfurling of Kristallnacht (the ‘Night of Broken Glass’), a three-day nationwide pogrom targeting Jews and their property. In January 1939, Hitler delivered a political speech and directly threatened the Jewish population of Europe:

“In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and have usually been ridiculed for it. During the time of my struggle for power, it was the Jewish race that laughed at my prophecies that I would one day lead the nation … and that among other things, I would settle the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of their face. Today I will once more be a prophet. If Jewish financiers in and outside Europe succeed in plunging us once more into a world war, then the result will not be the global victory of Jewish Bolshevism, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.”

“The idea of destroying the Jews had inhabited the deranged minds of anti-Semites long before Hitler, but only Hitler turned the fantasy into reality. Only Hitler achieved the political power, commanded the economic, technological and military resources to carry out that destruction. All his life he was obsessed by the thought of a holy war against the Jews, whom he saw as the Host of the Devil and as the Children of Darkness. He never swerved from his single-minded dedication to the goal of their destruction.”

Lucy S. Dawidowicz, historian

1. As a young man, Adolf Hitler struggled to earn a living in Vienna, where he was exposed to anti-Semitic ideas.

2. He joined the German army and fought in World War I, but felt betrayed by the November 1918 ceasefire.

3. Like many others, Hitler felt the surrender of Germany and the harsh war terms were engineered by Jews.

4. He joined a fringe party in 1919, rose to become its leader and transformed it into the Nazi Party.

5. Hitler rose to power in 1933, promising the restoration of German supremacy and action against its Jews.

Citation information

Title: “Adolf Hitler”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/adolf-hitler/

Date published: July 26, 2020

Date accessed: April 24, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.