The 19th century was a period of industrialisation, scientific discovery and the adoption of modern values. Despite this, it produced a resurgence in anti-Jewish prejudice. This 19th century anti-Semitism was particularly intense in Russia, where it triggered waves of violence against the country’s five million Jews.

Background

During the 1700s, several European rulers imposed restrictions on Jews, their culture and language. In some parts of 18th century Europe, Jews were still subject to discriminatory laws and regulations.

The Prussian king Frederick II, for example, passed laws restricting the number of Jews and banning them from marrying. In Austria, Jewish families were only permitted to have one son. In other states, Jews were obligated to pay additional taxes or face expulsion, while they were banned from holding political office or entering certain professions.

A few leaders were more enlightened. French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte, for instance, ordered the emancipation of the Jews in all French territories.

Early hope

At the start of the 19th century, anti-Semitism seemed another regressive idea that was quickly fading into history.

The 1800s was a century of industrial growth, political modernisation and social reform across western Europe. It delivered legal reforms and emancipation that improved the rights and status of Jews in many parts of Europe.

In France and Germany, two traditional crucibles of ‘Jew-hating’, there were optimistic changes for the better. An 1830 motion by the French government recognised Judaism as an official religion, alongside Catholic and Protestant Christianity.

Jews in the German-speaking states were granted economic and legal rights that exceeded those of their compatriots elsewhere. They were permitted to enter into legal contracts and purchase land and businesses. These reforms allowed German-speaking Jews to flourish. They became involved in banking and finance, law, medicine, higher education, theatre and the arts.

Mid-century revival

Despite these progressive reforms, anti-Jewish prejudices survived. There was a resurgence in anti-Semitism during the 1880s, driven partly by two significant political movements: Zionism and German unification.

Zionism was a political and cultural movement that sought the restoration of a Jewish homeland by creating a nation-state in Palestine. As Zionist leaders, groups and texts emerged, they called for greater Jewish unity and co-operation to achieve their goals.

The growth of Zionism in the 19th century, culminating the First Zionist Congress in 1897, fuelled fanciful conspiracy theories that Jews were formulating a plot to take over Europe or the world.

German nationalism

The push for German unification was another fertile ground for 19th-century anti-Semitism. Until 1871, there was no single German nation but a cluster of two dozen German-speaking kingdoms. Many nationalists wanted these kingdoms to unite to form a greater Germany, a nation that would rival the economic and military power of Britain, France and Russia.

The road to German unification was a difficult one, however, and was often blocked by political obstacles and regional self-interest. Many who supported unification became frustrated by the lack of progress – which, of course, some blamed this on the region’s Jews. Anti-Semitic writers claimed the Jews feared a united Germany. They much preferred the status quo of small, bickering kingdoms.

In 1868, a German writer, Hermann Goedsche, wrote of a secret coven of rabbis who met at midnight in a Jewish cemetery in Prague to devise plans for world domination. Goedsche was a known forger and an agent of the Prussian government, and his ‘revelation’ about a Jewish plot was actually plagiarised from an earlier text.

Rising anti-Semitism in France

Anti-Semitism also increased in France during the 19th century, fed by political division, instability and scapegoatism.

French Jews were attacked from both sides of the political divide – by socialists who opposed Jewish ownership of businesses and capital, and Catholic nationalists who condemned Jews on racial and religious grounds, while claiming they undermined national unity.

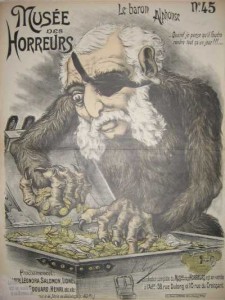

In some parts of France, anti-Jewish hatred had reached fever pitch by the late 1800s. The Ligue Nationale Antisemitique de France (‘French Anti-Semitic League’) was formed in 1889 and organised propaganda, riots and violent pogroms against local Jews. The group’s founder, Edouard Drumont, was a nationalist politician fond of invoking anti-Jewish conspiracy theories, including claims of corruption and bribery against other politicians and the prominent Jewish banking mogul Rothschild.

The Dreyfus affair

French anti-Semitism was brought to a head by the notorious ‘Dreyfus affair’ of the 1890s.

Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer of Jewish heritage who was accused of leaking military secrets to the Germans. He was sent to court martial and found guilty, more because of the intensity of French anti-Semitism than any evidence.

Dreyfus spent two years in a notorious colonial prison before Emile Zola published his famous essay, J’accuse, which condemned the French government of running a cover-up and playing host to institutional anti-Semitism. Dreyfus was subsequently acquitted and returned to military service.

Russian prejudices

The worst anti-Semitism of the late 1800s could be in the Russian Empire, which had one of the world’s largest Jewish populations (around five million by 1890).

As in Germany, Russian Jews benefited from new freedoms granted in the mid-1800s. They moved into middle-class occupations like business ownership, banking, teaching and manufacturing. This created resentment among non-Jewish Russians, though not enough to provoke much violence.

The situation for Russian Jews worsened considerably after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Alexander had been something of a reformist. He had abolished serfdom (bonded feudalism) in 1861 and some of his reforms had improved conditions for Russia’s Jews – but his ‘reward’ was to be blown to pieces by a bomb in the streets of St Petersburg.

Though Alexander was murdered by socialist revolutionaries, many Russians considered socialism and anarchism to be Jewish inventions – so Russia’s Jews, directly or indirectly, were held responsible.

Waves of pogroms

The backlash against Russian Jews was immediate. In 1882, the new tsar, Alexander III, ordered wide-ranging new restrictions for all Jews. They were prohibited from buying land or businesses, excluded from certain professions and expelled from some cities. Quotas restricted the number of Jews in state schools and universities.

State-run newspapers printed anti-Jewish propaganda while the ‘Black Hundred’, a group of conservative reactionaries loyal to the tsar, incited rumour and violence against Jewish communities. In the early 1880s, and again between 1903 and 1905, several thousand Russian Jews were killed in pogroms (race riots targeting Jews and their property).

Jews continued to serve as a scapegoat for Russia’s woes into the 20th century. Nicholas II, who took the throne as tsar in 1894, was a fervent anti-Semite who blamed almost every significant problem on the Jews and their influence. One of Nicholas’ prime ministers, Sergei Witte, wrote of the tsar:

“The Emperor was surrounded by avowed Jew-haters, such as Trepov, Plehve, Ignatiev, and the leaders of the Black Hundreds. As for his personal attitude towards the Jews, I recall that whenever I drew his attention to the fact that anti-Jewish riots could not be tolerated, he either went silent, or remarked “But it is the Jews themselves who are to blame”.”

The Protocols of Zion

The notorious anti-Semitic forgery The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion was a product of this poisoned environment.

The Protocols were written and circulated sometime around 1900, probably by agents of Nicholas’ secret police force, the Okhrana, as a means of strengthening his rule. They first appeared in print in 1903 and their content contributed to another wave of violent pogroms against Russian Jews.

In the end, Nicholas’ poor judgement and irrational anti-Semitism cost him both the throne and his life. As revolutionary forces were building in Russia in late 1916 and early 1917, he continued to assert that it was “all Jewish work”. Nicholas was forced to abdicate in March 1917, and he and his family were murdered by communist revolutionaries in July the following year.

A historian’s view:

“Dramatic change had swept across Europe during the course of the century, and the Jews provided a convenient scapegoat for many of those whose existence was destabilised, as old established social roles were overturned. The political revolutions that furthered democracy across Europe meant a loss of status and power for the old nobility and clergy. In the estimation of some of the losers, the Jews were the most obvious gainers, and anti-Jewish resentment built. Similarly, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism meant new challenges to agricultural labourers and more intense competition for shopkeepers. To them, too, the Jews seemed the group who most benefited from these painful changes.”

Naomi E. Pasachoff

1. Anti-Semitic violence decreased after the Middle Ages, although prejudice against the Jews did not.

2. European Jews enjoyed some emancipation and improved rights from the early to mid-1800s.

3. The emergence of Zionism gave rise to conspiracy theories about the Jews seeking world domination.

4. Anti-Semitism increased in France and Germany, with the Jews as scapegoats for domestic problems.

5. In Russia, Jews were indirectly blamed and subject to recriminations for the assassination of Alexander II.

Citation information

Title: “19th century anti-Semitism”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/19th-century-anti-semitism/

Date published: July 23, 2020

Date accessed: April 25, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.