The Thermidorian Reaction began with the toppling of Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794. Reactionaries set to work within hours of Robespierre’s head hitting the wicker basket. They sought to create a conservative republic, free of centralised power, rigid economic controls, contrived religion and state terror. Within a month, the Thermidorian Convention had repealed the legislation of the Terror and disempowered its main organs, particularly the Committee of Public Safety. The Thermidorians and their supporters also initiated a ‘White Terror’, to purge government and society of its remaining Jacobins. In August 1795 they passed a new constitution that dissolved the National Convention and replaced it with the Directory, effective November 1795. In its short 15-month life the Thermidorian regime was unpopular with most of the people. It failed to address most of their grievances or improve their lives, and repeated several mistakes made by earlier governments. According to historian Paul Hanson, the Thermidorian period has “long been seen as a sort of revolutionary wasteland, a desultory interregnum between Robespierre and Napoleon”, chiefly because it lacked great leaders, landmark policies and significant events.

As a consequence, the Thermidorian Convention evolved into a strange and disjointed assembly, often lacking in leadership and consensus. The majority of the Thermidorian deputies were conservative Republicans. They wanted to wind back the Terror and restore stability and control to the government, without allowing the restoration of either Jacobinism or the monarchy. In their first month, the Thermidorians watered down the power of the Committee of Public Safety, leaving it in charge of the war effort but reallocating its other responsibilities to several new committees. Wary that these committees might again accumulate power, the Convention decreed that one-quarter of committee positions would be turned over each month. The Thermidorians abolished the policies of the Jacobin-Robespierrist regime, repealing the Law of Suspects, the Law of 22 Prairial and the Law of Maximum. Deputies were dispatched to the provinces to oversee these changes, to ensure that Jacobins were removed from positions of authority and to bring the Reign of Terror to an end.

Much of the violence of the White Terror was spontaneous and anarchic. There were several instances of Jacobin prisoners being hauled from cells and slaughtered, an echo of the 1792 September Massacres. Some of the killings of the White Terror were carried out with legal approval. The National Convention kept the Revolutionary Tribunal in operation until the end of May 1795. During this time it was charged, tried and dispatched dozens of Jacobin terrorists, albeit with fairer legal processes than the Jacobins had employed themselves. Among those executed by the Tribunal during the Thermidorian period were the notorious Nantes représentant en mission Jean-Baptiste Carrier and the Tribunal’s former prosecutor, Antoine Fouquier-Tinville. A few Jacobins who participated in the anti-Robespierre coup escaped with their lives. Bertrand Barère and Jean-Marie Collot d’Herbois, who had served on the Committee of Public Safety with Robespierre, were both tried and deported to the French colonies.

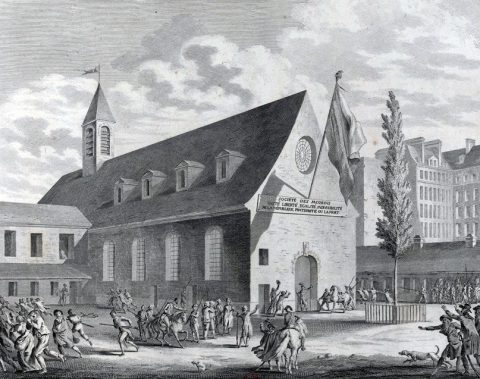

In Paris, a good deal of political violence was carried out by the so-called muscadins (‘perfume-wearers’) or jeunesse dorée (‘gilded youth’). Identifiable by their fashionable dress, their swagger and turns of phrase, most jeunesse dorée were young dandies from the bourgeoisie. They came from the more affluent suburbs of central and western Paris; those that worked held professional positions in family businesses, law firms or the bureaucracy. The jeunesse dorée, through their wealth and connections, managed to avoid the bloodshed and military service of the revolution. The removal of Robespierre drew them out of hiding and onto the streets in defence of the new political order. Their politics were anti-Jacobin and moderate republican. They also tolerated royalists and some of their number were probably closet monarchists. In late 1794 and 1795, the jeunesse dorée took to the streets like foppish, overdressed sans-culottes, condemning Jacobin policies, intimidating Jacobin sympathisers and destroying remnants of the old order. Much of this was minor or symbolic, however, gangs of jeunesse dorée went about armed with canes and clubs, beating Jacobin sympathisers and engaging in street battles with the sans-culottes. The jeunesse dorée were more likely to deliver a good thrashing than carry out political killings, however, their presence in Paris and some other cities was intimidating enough to contribute to the suppression of Jacobinism.

“With Robespierre gone and his supporters imprisoned, guillotined or so dumbfounded that they were incapable of acting, the Convention drifted aimlessly, disconnected from its social base, as though suspended in a vacuum. But this situation did not last long. The muscadins [well to do young men] soon appeared, with their square-cut coats, their enormous cravats and their weighted cudgels – their ‘executive power’, they claimed. A few brawls in the public gardens and they were masters of the Paris streets, driving out the last hard-nosed revolutionaries of the Year II. Meanwhile, in the Convention, a new moderate party had been formed… no sooner had the Convention thrown off the Jacobin yoke than it found itself under that of the ‘gilded youth’… it was [still] a prisoner of its own troops; it had simply changed masters.”

Francois Gendron, historian

While the Thermidorians and their supporters purged France of Jacobins, they showed more toleration to other political factions. Many Girondinists and Dantonists who had survived the Terror were permitted back into public life. The Thermidorians also repealed the Convention’s death sentence and banishment order against émigrés. Buoyed by the removal of Robespierre and the apparent moderation of the Thermidorian Convention, many émigrés chose to end their exile and return to France, some hoping to regain their property, some plotting the restoration of the monarchy. “We are now in the thick of the debate”, one anonymous émigré wrote to another in 1795. “In the galleries, they talk of the Constitution of 1791, in private of bringing back the king”. These reports of returning émigrés did not please everyone. In the spring of 1795 a Republican newspaper, the Moniteur, claimed that “the main roads are swarming with émigrés” who, having taken up arms against France, were returning “with the same bitterness which made them leave”. Rumours abounded that an émigré army would assemble in France and install ‘Little Capet’ – Louis XVI’s younger brother, the Count of Provence – as the new king.

The Thermidorians remained hostile to religion but wisely decided to disentangle religion from government. The Thermidorian Convention quickly repealed Robespierre’s decree on the Supreme Being. In September 1794, the deputies moved that the state was no longer responsible for paying the salaries of clergymen, a move that effectively ended the Constitutional Church. On February 21st 1795, the Thermidorian Convention voted to allow freedom of religion and worship, though this came with strict conditions. Religious dress, symbols, processions and bell ringing were all banned, while any religious gathering was deemed to be “subject to the surveillance of the authorities”. The Thermidorians were tolerant enough to allow freedom of religion, provided it was done privately, however they feared the restoration of the Catholic church. When the restrictions of February 1795 were ignored by many Catholic clergymen, the Convention followed the example of 1791 and required clerics to swear oaths of loyalty to public laws.

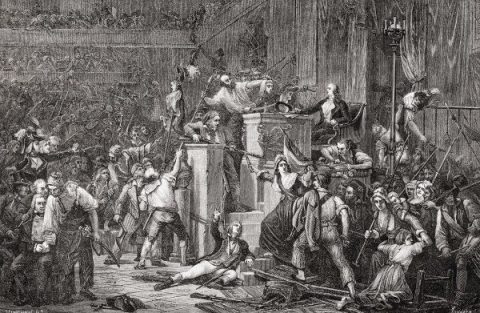

Economically, the Thermidorians were pro-capitalists who favoured policies conducive to business and commerce. Thermidorian economic policy focused on ending price controls, deregulating trade and restoring paper currency. Laws and measures enforcing price controls and combating speculation were wound back, and in December 1794 the Convention formally abolished the Maximum. Meanwhile, the government began printing and releasing assignats. The outcomes were disastrous and were exacerbated by a poor harvest in 1794 and a freezing winter in 1794-95. In scenes reminiscent of 1789, Paris and other cities found themselves critically short of food. Prices for food and fuel spiralled and, in Paris, hundreds of people starved, froze to death or committed suicide. By April 1795 assignats had fallen to less than one-tenth of their value in 1790. On May 20th (1 Prairial) the sans-culottes of Paris mobilised and invaded the hall of the Convention, murdering a deputy named Jean-Bertrand Féraud and parading his head on a pike. This time, however, the sans-culottes had no effective leadership and little support in the Convention. The Thermidorians received a petition from the mob but then called in the National Guard to disarm and suppress them.

1. The Thermidorian Reaction was the 15-month long period between the overthrow of Robespierre and the formation of the Directory. During this time the Convention was dominated by deputies from the Plain.

2. The Thermidorians were a loose coalition of deputies. Generally speaking, they were conservative Republicans who wanted to rid France of the Jacobins and liberalise the economy.

3. They quickly wound back the Terror, repealing laws and weakening the Committee of Public Safety, then embarked on a ‘White Terror’ to purge the government and nation of Jacobins.

4. The Thermidorians also ended the Constitutional Church and permitted freedom of religion, though religious worship was strictly controlled. They also repealed the Maximum and began reissuing assignats.

5. The economic policies of the Thermidorians proved disastrous and by the spring of 1795 cities like Paris were again critically short of food and at risk of famine. This led to a sans-culotte uprising on May 20th, where the Convention itself was invaded.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn and S. Thompson, “The Thermidorian Reaction”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/thermidorian-reaction/.