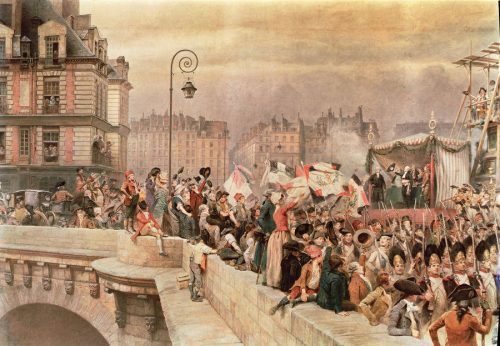

The September Massacres were murderous riots that erupted in Paris in the first week of September 1792. Inspired by fears of an imminent military invasion and inflammatory talk from members of the Paris Commune, mobs of ordinary Parisians attacked and murdered individuals perceived to be of the old order, most of them hauled from the city’s prisons. The September Massacres marked the worst violence of the revolution to that point, alarming moderates inside France and horrifying the rest of Europe.

Summary

With the Revolutionary War proceeding poorly and Prussian troops advancing further into French territory, Paris was gripped by the fear of a possible military invasion. Incited by the newly radicalised Commune, powerful orators and provocative journalists, the city’s lower classes took matters into their own hands.

On September 2nd, gangs of armed sans-culottes stormed most of the city’s prisons and killed between 1,100 and 1,400 prisoners. Among the victims of this butchery were hundreds of Swiss Guards and royal soldiers, detained after the August 10th attack on the Tuileries, as well as clergymen, nobles and suspected counter-revolutionaries. Most of the victims, however, were ordinary criminals with no political affiliation.

The September Massacres were widely reported across Europe, the news of this barbarism causing disgust and outrage. To critics of the revolution, it was evidence that Paris was in a state of bloodthirsty anarchy. Within the government, the September Massacres widened the gulf between the moderate Girondins and radical Jacobins.

Context and causes

War, insurrection and paranoia provided the context for the violence of September 1792. On August 1st, the Prussian military commander Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, issued a notorious manifesto that threatened to wreak vengeance on Paris if the French royal family was harmed.

The Brunswick Manifesto, as it became known, was intended to intimidate the people of Paris. Instead, it had the opposite effect, Brunswick’s threats inspiring Parisians to defend the fatherland and rally to combat foreign imperialists.

There were two significant developments on August 19th: the Marquis de Lafayette fled the revolution and was taken prisoner by the Austrians, while Prussian forces crossed the border and penetrated into French territory.

The following day, these Prussian troops engaged the French Revolutionary Army at Verdun. Prussian militarism and professionalism prevailed and the French were defeated after 10 days. This defeat opened the way for the Prussians to march on Paris.

The Commune acts

News of the Prussian victory at Verdun reached Paris on Sunday morning, September 2nd 1792. At this point, the Legislative Assembly was preparing for its own dissolution and organising elections for the National Convention. Because of this transition, France was effectively without a national government.

This power vacuum was exploited by the Paris Commune, now under the control of radicals like Georges Danton, Jean-Paul Marat, Jacques Hébert and Fabre d’Églantine. The Commune declared a state of emergency, while the sectional assemblies of Paris went further, demanding a popular insurrection and immediate action against suspected counter-revolutionaries.

The radicals had soft targets in mind: Swiss Guards, Royalist soldiers, spies, foreigners, clergymen and aristocrats who were languishing in the city’s prisons. These prisoners were not just enemies of the state – they posed a threat if the Prussians reached Paris and managed to liberate them.

Prisoners butchered

The first wave of violence began in the late afternoon of September 2nd, when a mob intercepted a group of detainees being admitted to the Abbeye prison. All were seized and executed.

As the night progressed more prisons were raided, their inmates hauled from cells and killed in cold blood. Most were executed immediately; some were given a mock trial and subjected to accusations and interrogation (though this only extended their humiliation and delayed their execution). In a few cases, the killing descended into abject butchery, with corpses dismembered, eviscerated and either paraded or put on public display.

The attacks on prisons continued until the evening of September 6th. In four days, the September Massacres claimed between 1,100 and 1,400 lives. Of the dead, around a third were legitimate counter-revolutionary suspects. The vast majority were ordinary criminals – thieves, swindlers, prostitutes, drunks and debtors – whose only misfortune was being behind bars at the wrong time.

Prominent victims

The September massacres nevertheless had some prominent victims. Around 200 of the dead were clergymen and three were bishops. Copycat riots in Orléans and Versailles on September 9th also claimed some notable figures.

At Versailles, an angry mob broke into the prison there and slaughtered around 30 inmates. One was Charles d’Abancour, a former minister to Louis XVI. Another was Louis, Duke of Brissac, a former governor of Paris and commander of the king’s bodyguard.

Perhaps the highest profile victim was Marie Thérèse, Princess de Lamballe, once a prominent lady-in-waiting to Marie Antoinette. The princess was not a political figure but her proximity to the queen had made her a target for political pornographers; their libelles had portrayed her as Antoinette’s lesbian lover.

On September 3rd, Marie Thérèse was snatched from a prison in eastern Paris, given a brief but humiliating show trial, then handed to a waiting mob. According to different reports, some of them conflicting, she was publicly raped, murdered and dismembered, her head removed and her breasts and genitals hacked off. The severed head was paraded outside Antoinette’s window on a pike, though the queen did not see it.

Reaction in Europe

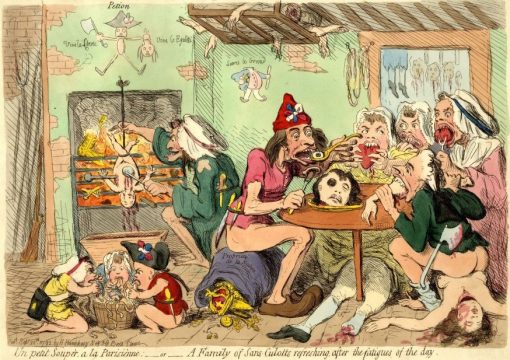

Reports of the September Massacres invoked outrage and horror when they reached London. The London press ran gory accounts of the violence – and some false reports of cannibalism and devil worship. The cartoonist James Gillray’s famous caricature of Paris cans culottes, Un petit souper (above) appeared shortly after the massacres.

The killings of September 1792 triggered a further exodus of nobles and affluent bourgeoisie from France, many of whom sought to relocate to England. This led the English parliament to pass a law regulating and restricting refugees, for fear that radical revolutionaries might be hiding among them.

In a speech given a few weeks after the massacres, Edmund Burke spoke in favour of this bill, describing the revolutionaries thus:

“When they smile, I see blood trickling down their faces. I see their insidious purposes. I see that the object of all their cajoling is blood! I now warn my countrymen to beware of these execrable philosophers, whose only object it is to destroy everything that is good here, and to establish immorality and murder by precept and example.”

Political effects

Politically, the September Massacres were an ominous forebear of the worst violence of the Reign of Terror.

While foreigners and moderates were aghast at the ferocity of the popular violence, radical Jacobins like Maximilien Robespierre and Georges Danton defended it. Robespierre declared himself to be appalled by the worst of the killings, yet showed little sympathy for its victims. “Save some tears for other greater calamities”, he reportedly said, “particularly the countless millions who through the ages have suffered the torments of political and social oppression… Do you want a revolution without revolution?”

The shadow of the September Massacres hung over the elections for the new National Convention, as well as the Convention’s first sessions. Deputies to the Convention met in a city gripped by revolutionary insurrection. They knew the capabilities of the people and the fate of those who opposed the revolution.

As for the mobs of Paris, their mood was placated by the first resolutions of the National Convention and the French victory at the Battle of Valmy (September 20th), which pushed the Austrians and Prussians out of France and ended the foreign military threat to Paris.

“Following the September Massacres, the vision of revolution put forth by the Jacobins implied that a revolution was often uncontrollable and inherently violent, but simultaneously purposed and constructive. As Robespierre memorably asked in the wake of the massacres, ‘Do you want a revolution without a revolution?’, implying that a revolution necessarily entailed a certain amount of disruption and violence.”

Mary Ashburn Miller, historian

1. The September Massacres were a series of murderous riots and rampages that broke out in Paris on September 2nd 1792 and continued for several days.

2. The targets of these riots were the city’s prisons. These prisons housed, among others, suspected counter-revolutionaries, royalist soldiers, members of the Swiss Guard, clergymen and former nobles.

3. The riots were precipitated by the Austro-Prussian invasion of France and their victory at Verdun. This appeared to open a path for the coalition forces to march on Paris.

4. The violence of early September saw between 1,100 and 1,400 people murdered. This prompted outrage in Britain and among moderate revolutionaries. It also fuelled a new wave of émigrés.

5. Politically, the September Massacres were endorsed by radical Jacobins like Robespierre, who justified them as a legitimate revolutionary act, an expression of the will of the people.

Citation information

Title: ‘The September Massacres’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/september-massacres/

Date published: September 13, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: April 25, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.