When Louis XVI‘s ministers proposed fiscal and taxation reforms in the 1780s, they were resisted by elements of the Ancien Régime. One significant institution to block these reforms was the parlements, France’s highest courts. By the late 1780s, this resistance had become a visible power struggle between the king and his parlements.

What were the parlements?

The parlements were the supreme courts of law in pre-revolutionary France. They served as the nation’s highest courts of appeal, in a similar way to the United States Supreme Court, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and the High Court of Australia.

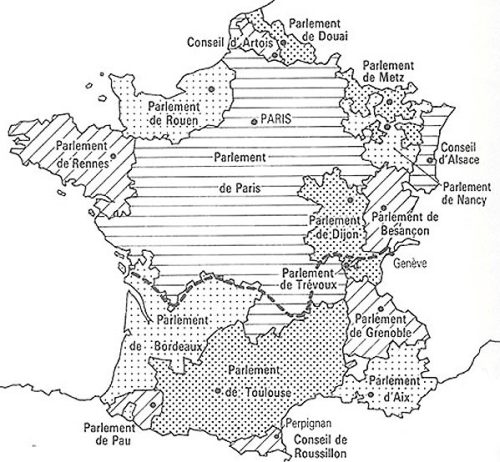

The parlements were ancient institutions that traced their history back to the 13th century. At the start of the 18th century, France had 13 different parlements, each with its own jurisdiction or area of operation. Each parlement was manned by at least 12 magistrates, all of whom were noblesse du robe and thus members of the Second Estate.

The 13 parlements were all equal, at least in theory, but the parlement of Paris – by virtue of its size, its proximity to the king and its interaction with the royal government – exercised more power and influence than the others.

A check on royal power

Historically, the parlements had often served as a check or limitation on royal power. While the parlements could not initiate new laws or amend or abolish existing laws, they neverthless played some role in the legislative process.

According to custom, the parlement of Paris scrutinised and registered new laws and royal edicts before their final adoption. This gave the Paris parlement the ability to block royal edicts, either as a protest against specific policies or as a means of exerting influence over the monarch.

If the parlement refused to register a law, it would publish a remonstrance (a written explanation of its concerns and objections to the law). If this occurred, the king could summon justices of the parlement to a lit de justice (‘bed of justice’, in essence, a royal session of the parlement). At a lit de justice, the king could formally override the remonstrance and order registration of the law. Alternatively, the king could use lettres de cachet to intimidate, exile or imprison magistrates of the parlement in order to force their compliance.

Louis XV versus the parlements

The relationship between the king and the parlements was an important aspect of French royal government in the 17th and 18th centuries. The reign of Louis XV (1715-1774) was frequently disrupted by tension and conflict with the parlements.

This became particularly severe in the last quarter of Louis XV’s reign when opposition from the parlements made governing almost impossible. From 1763, the Paris parlement blocked a series of royal reforms and policies, including a new instalment of the vingtième tax.

In 1766, Louis XV famously appeared at a session of the parlement and in the strongest terms informed its judges that his royal sovereignty was supreme. Five years later, Louis and his chancellor, Maupeou, moved to abolish the parlements altogether, replacing them with councils manned by appointed officials. The parlements were restored to their previous status when Louis XVI took the throne in 1774.

Blocking fiscal reforms

During Louis XVI’s reign, the Paris parlement consistently opposed the government’s fiscal policies. It objected to the raising of new loans, arguing that the national deficit should be managed by reducing expenditure. The lavish spending of the royal court – already under some public scrutiny – was also criticised by the parlement.

Meanwhile, the king’s controller-general of finances, Charles Calonne, was developing his own set of reforms to address the nation’s fiscal crisis. He hoped to increase government revenue by stimulating the economy and removing personal exemptions from taxation.

Calonne’s proposed reforms, drafted in 1786, included the imposition of a land tax – without any exemption for the First and Second Estates. Calonne knew the Paris parlement would block his reforms so he instead sought endorsement from an Assembly of Notables. The Notables rejected Calonne’s proposals and his reforms were abandoned.

Open confrontation

In April 1787, the king dismissed Calonne and replaced him with Etienne Brienne, previously the chairman of the Assembly of Notables. Brienne developed his own package of reforms that were quite similar to those of Calonnes. He hoped to stimulate France’s production and trade by winding back internal regulation, while abolishing the corvée, introducing a land tax and ending exemptions from personal taxation.

In June 1787, Brienne began passing these reforms as edicts. To his credit, Brienne convinced the Paris parlement to register the majority of his reforms. But the parlement refused to endorse any new tax, nor would it support radical changes to taxation exemptions. Those changes, the magistrates argued, were “contrary to the rights of the nation”. Changes of that magnitude, the parlement declared, could only be affirmed by an Estates General.

This defiance brought the parlements into open confrontation with the king. On August 6th 1787, Louis XVI, acting on Brienne’s advice, convened a lit de justice where he dissolved the Paris and Bordeaux parlements. Lettres de cachet were issued against these magistrates, sending them into exile at Troyes, 110 miles east of Paris.

Brienne believed that if the magistrates were detained in Troyes, well away from the public pressures of Paris, they would eventually back down. Instead, the exiled magistrates at Troyes wrote to France’s other parlements, urging them to refuse registration to any tax edicts.

Public attitudes

The king’s attack on the parlements also sparked a public backlash in Paris, with riotous assemblies and protests through the rest of August. In the end, the parlements won the day. On September 24th, the king allowed the magistrates to return to Paris, and their arrival in early October was met with public fanfare and celebration. Brienne’s taxation reforms, meanwhile, remained unregistered.

For the next eight months, the king, his ministers and the parlement of Paris engaged in a political tug-of-war. In January 1788, the parlement moved to declare lettres de cachet illegal; the king responded by summoning a lit de justice to nullify its decision. In early May, the parlement issued a ‘Declaration of the Fundamental Laws of France’, an attempt to assert its judicial independence; the king responded with lettres de cachet that ordered the arrest of two magistrates.

On May 8th, Louis XVI followed in the steps of his grandfather, Louis XV, and attempted to neuter the parlements altogether. All future edicts, the king ruled, would be registered by an appointed ‘plenary court’. This royal attack on the parlements triggered yet another wave of public violence. Riots broke out in Paris and in Grenoble locals pelted government soldiers with tiles. Protests against the king’s treatment of the parlements would continue for weeks and were only eased by the convocation of the Estates General (August 8th 1788).

“Historians tend to judge the parlements harshly, arguing in effect that they were chiefly responsible for the breakdown of the ancien regime. In a tenacious defence of privilege – not least their own – they lost sight of the larger constellation of problems confronting the monarchy. Yet this was not how public opinion viewed their stance. The parlements’ resistance to the royal will enjoyed huge support among the educated classes and it was sustained almost to the end… The parlement of Paris… was able to pose successfully as the champion of the law at a time when the absolute monarchy appeared completely reckless…”

P. M. Jones, historian

1. The parlements were the highest law courts and courts of appeal in France. The parlements were also responsible for registering royal laws and edicts, so they had a role in the legislative process.

2. France had 13 parlements, the most powerful of which was located in Paris. It often refused to register laws, outlining its reasons in remonstrances. The king could only force registration at a lit de justice.

3. The Paris parlement came into conflict with the monarchy in 1787-88, when it refused to register Brienne’s edicts implementing a new land tax.

4. The king responded by sending the Paris parlement into exile at Troyes, hoping to force their compliance, however this triggered significant public unrest and some violence.

5. The Paris parlement was eventually restored but conflict with the king and his ministers continued in the first half of 1788, culminating in the summoning of the Estates General.

Arthur Young on public views about the parlements (1792)

Citation information

Title: ‘The parlements‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/parlements/

Date published: October 9, 2019

Date updated: November 8, 2023

Date accessed: April 18, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.