Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) was the wife of Louis XVI and the Queen of France between 1774 and 1792. Popular accounts have painted Antoinette as a disruptive and despised figure. If folklore is to be believed, she was almost single-handedly responsible for inciting the French Revolution. According to legend, Marie Antoinette’s sexual appetites discredited the regime, humiliated her husband and produced several bastard children. Her political intriguing and henpecking of Louis XVI were responsible for the king’s poor decision-making. Her profligate spending on costumes, jewellery, trinkets and trivialities pushed the nation to the verge of bankruptcy. Even worse, the French queen demonstrated utter disregard for the suffering of those she ruled, an attitude reflected in the notorious “let them eat cake” meme. As often happens in history, only some of this was true. The folklore surrounding Marie Antoinette is a construct of libels, exaggerations and fictions. She has become a villainous scapegoat for the French Revolution when evidence suggests she was mostly innocent of the allegations made against her.

Marie Antoinette began life as an Austrian princess, the 16th child of Empress Maria Theresa. Like other junior princesses, she was given a cursory education then hustled into an arranged marriage to further the political ambitions of her parents. In 1770, just months after Antoinette’s 14th birthday, she was carted off to France to marry Louis Bourbon, the Dauphin or heir to the French throne. Their union was a purely political, designed to align the two great Catholic powers of France and Austria, yet it was steeped in ceremony and tradition. A complicated ritual required Antoinette to strip her clothing at the border and cross into France naked; she was then fitted into French clothes by French maids. Antoinette’s wedding to the pudgy 15-year-old prince – whom she had never previously met – was an extravagant affair. Their early relationship was problematic. Louis and Antoinette’s initial attempts at sexual intercourse were watched by numerous courtiers and, perhaps unsurprisingly, never completed. It took several years for their marriage to be properly consummated, while Antoinette did not fall pregnant until seven years after her wedding. Yet despite these early fumblings and the lack of romance in their marriage, the king and queen developed a measure of affection and devotion to each other.

Antoinette found her days in the French court as difficult as the nights in her husband’s bedroom. Versailles was a marked contrast to the refined gentility of her mother’s court in Austria. Couples flirted openly and men urinated on indoor walls, while idle aristocrats occupied their time with sexual affairs, political intrigues and gossip. Antoinette came to hate the politics and monotonous rituals of court, making several powerful enemies, most notably Louis XV’s mistress Madame du Barry. As both a newcomer and a foreigner, the young queen became the target of court gossip and malicious intrigues. The king and queen’s sexual problems were common knowledge so rumours abounded that the Louis was impotent and his wife was frigid – or, worse, preferred the company of other men. This poisonous gossip led Antoinette to withdraw into her own inner circle. She spent large amounts of time at the Petit Trianon, a small château built for royal mistresses, rather than the main palace at Versailles. There she surrounded herself with favourites like Princess de Lamballe and the Polignac family, on whom she showered money and gifts.

By the 1780s, court gossip against Antoinette had leaked into the public arena, where the queen was targeted by scandalous rumours and libelles. Antoinette gave birth to a daughter in 1778, followed by sons in 1781 and 1785. All were immediately followed by rumours that the king was not the natural father. Antoinette was also condemned for her extravagance and wild spending on clothing, jewellery and court favourites. One thorny issue was the queen’s order to construct a mock rural village, La Hameau de la Reine (‘The Queen’s hamlet’) near the Petit Trianon. The hamlet had its own working farm, stocked with animals imported from Switzerland. To pass the time, Antoinette would dress in peasant clothing and carry out the duties of a shepherdess or milkmaid (albeit with buckets made of fine porcelain) before returning to her royal comforts. All this was valuable ammunition for her detractors. It was not enough that entire villages had to be constructed for Antoinette’s leisure, she also seemed to delight in imitative ridicule of the French peasantry.

One story about Marie Antoinette’s attitude to the common people has survived all others. When told that French workers were deprived of bread, legend has it that Antoinette replied: “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche” (“then let them eat cake”). It is doubtful she said anything of the kind. The same remark was attributed to several apocryphal queens and “great princesses”, long before Antoinette had even arrived in France. The same remarked had also appeared in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau when Antoinette was still a child. Extant sources suggest the queen was actually more cautious and measured with her remarks. She often showed a measure of concern for the poor, at least in comparison to others of her rank. When hearing of food shortages in one French town, the queen is reported to have said: “It is quite certain that in seeing the people who treat us so well despite their own misfortune, we are more obliged than ever to work hard for their happiness.”

“Everyone knew now why the state debts had been piled up to so monstrous a figure, why paper money was continually depreciating in value, why bread became dearer and dearer and the burden of taxation heavier. It was because this harlot who was their Queen had the walls of one of her rooms at the Trianon studded with brilliants, because she had secretly sent her brother Joseph in Austria a hundred gold millions to help him carry on his war, and because she had lavished pensions and sinecures upon her bedfellows, male and female… Through the length and breadth of the land, she was spoken of as ‘Madame Deficit’. It was as if she had been branded between the shoulders with this stigma.”

Stefan Zweig, historian

Antoinette’s extravagant spending was another target for the gutter press and there is more coherent evidence of this. The queen was renowned for her fine taste, particularly her affection for new and grandiose fashions, jewellery and hairpieces. Like the other women at Versailles, she was fond of elaborate headdresses, reportedly once wearing a wig in the form of a battleship to commemorate a famous naval victory. In 1776 Antoinette had a dress allowance of 150,000 livres but managed to spend more than three times that amount. In the first years of her reign, the queen was also a prolific gambler who wiled away the nights at Versailles by playing a card game called lansquenet, usually for gold pieces. In time, Antoinette’s chambers became a haunt for card sharps and professional gamblers, despite the king having explicitly banned gambling at Versailles. As the queen matured and bore children, and her relationship with her husband developed, she became less reliant on these games and amusements. Antoinette also became more circumspect with her dress and more frugal with her spending, her expenditures reducing through the 1780s. The queen played no part in the ‘diamond necklace affair‘ of 1785-1786, though her reputation suffered because of it. But the queen’s early extravagance had permanently coloured public perceptions of her and by 1788 she had acquired the nickname ‘Madame Deficit’, suggesting that her spending was responsible for the national debt.

Antoinette was famously subjected to ridicule and defamatory abuse in numerous libelles. Before 1789, the queen was but one of several popular targets for the gutter press (historian Robert Darnton suggests that in the 1780s about one in ten libelles directly attacked Marie Antoinette). The relaxation of censorship and the events of 1789 changed that significantly. In 1789 the royal court was swamped by a tsunami of vitriolic and pornographic libelles – and Antoinette was the protagonist in most of them. Smutty pamphlets dubbed her l’Autrichienne (‘the Austrian bitch’) and accused her of adultery, cuckoldry, tribadism (lesbianism), masturbation and incest. She was also accused of political intriguing, manipulation of the king and espionage on behalf of her native Austria. There was a grain of truth in accounts of Antoinette’s political activism but the stories of Antoinette’s sexual antics were an outrageous fiction. If the queen was sexually active outside her husband’s boudoir then she concealed it well.

Antoinette’s political views were undoubtedly conservative and reactionary. She despised how the revolution eroded Louis’ absolutism, believing that radicals and deceivers had come between the king and his people. Antoinette did what she could to restore his political authority – but her political influence was negligible, despite what has been claimed by propagandists and Republicans. Like other women of her era, the queen had no capacity to make decisions on matters of policy or government. She did have the ear of her husband, which may have influenced his decisions. The royal family’s flight to Varennes was undoubtedly sanctioned by Antoinette and organised by her favourite, Count Axel Fersen. Earlier, Antoinette had communicated regularly on matters of politics with men like Honore Mirabeau, Antoine Barnave and Charles Talleyrand. She did this to advance her husband’s interests, however, she could not bring herself to fully trust the agents of the Third Estate.

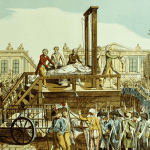

The road to Antoinette’s demise began on August 10th 1792, when thousands of Parisians attacked the Tuileries palace and forced the Legislative Assembly to suspend the monarchy. On August 13th the royal family was relocated to the Temple fortress, where they were held under close guard and in austere conditions. Antoinette languished in the Temple for 14 months, enduring the execution of her husband and isolation from the outside world. There were several royalist plots to liberate the former queen but none came to fruition. In August 1793 Antoinette was separated from her children and shifted to a dungeon in the Conciergerie. There she was watched by male guards around the clock, even when dressing or attending to her toilet. On October 14th the deposed queen, now titled as the Widow Capet, was presented for trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal. She faced a litany of charges – from political treachery to orchestrating massacres, to sexually abusing her own children – and the outcome was largely predetermined. At noon on October 16th, Marie Antoinette was driven to the Place de la Révolution and, like her husband 10 months before, placed under the guillotine.

1. Marie Antoinette was an Austrian princess who married Louis, Dauphin of France, in 1770. She became Queen of France four years later.

2. Louis and Antoinette were unable to consummate their marriage or conceive a child, while Antoinette found it difficult to adjust to life in the royal court.

3. Antoinette became publicly disliked for her extravagant spending, which included clothing and fashion, wigs, parties, gambling, gifts to favourites and an entire mock peasant village at Versailles.

4. By 1789, Antoinette was being buffeted by intense and poisonous libelles (propaganda pieces) that accused her of wastefulness, political manipulation and sexual excesses.

5. By the 1790s Marie Antoinette was perhaps the most despised of all Ancien Régime figures. After being toppled from the throne in August 1792 she spent 14 months in prison before being given a show trial and sent for guillotining.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn and S. Thompson, “Marie Antoinette”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/marie-antoinette/.