In the 1600s and 1700s, France’s rulers maintained an aggressive foreign policy that saw the nation participate in several imperial wars. These wars helped lay the foundation for revolution in France, chiefly by increasing government spending and state debt to unsustainable levels. The last of them, the Seven Years’ War, also saw France lose possession of its lucrative colonies in North America.

The French Empire

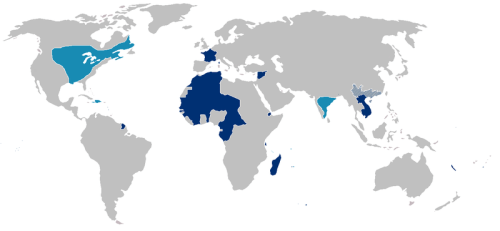

By the late 1600s, France was both a European continental power and an imperial power. The French Empire was the second largest in the world after the British Empire. It included large swathes of central and eastern North America, down to the Mississippi valley and the Gulf of Mexico, islands in the Caribbean Sea and most of north west Africa. French colonialism was also beginning to take root in eastern India (from Pondicherry to Bengal) and in south-east Asia (in modern-day Thailand, Laos and Vietnam).

The French Empire was supported, supplied and protected by significant naval and mercantile fleets. France’s colonies produced significant amounts of wealth for the nation, providing additional land, raw materials, commodities and labour. The income from colonial resources and profits supercharged the growth of French capitalism in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

Rivalry with Britain

France’s imperial growth also generated tension and conflict with Britain. The royal government increased its military spending dramatically in the second half of the 1600s. The ‘Sun King’, Louis XIV, used war and imperial rivalry as a means of strengthening his domestic power.

It is difficult to calculate precise figures for Louis XIV’s military spending program in the late 1600 but it certainly exceeded 600 million livres. At the king’s order, the national army was greatly expanded while soldiers were equipped with better artillery pieces and flintlock rifles, a new development in small arms. The government also improved military infrastructure. Fortresses, barracks and garrison houses were replaced, updated or built anew.

This expansion caused an explosion in government expenditure. Before 1660, for example, the government spent an average of 347,000 livres a year on fortresses. By the 1680s, this had blown out to more than eight million livres per annum.

The War of Devolution

By the mid-1660s, Louis XIV was seeking an opportunity to test his revitalised military in war. An opportunity came in the spring of 1667 when he declared war against Spain, following a territorial dispute over the Spanish Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). The king raised some 50,000 soldiers in less than a week and ordered them across the border to engage the Spaniards.

Sensing the propaganda value of this conflict, Louis accompanied his generals and spent much of the war at the front line (albeit with most of the comforts of home). He participated in several battles and sieges, and commissioned artists to capture scenes of his bravery and leadership.

The War of Devolution, as this conflict became known, lasted barely a year before Louis was forced to negotiate peace. France’s involvement produced nothing except some small territorial gains in Flanders. In return, the war drained approximately 18 million livres from the royal treasury.

The Nine Years’ War

This failed adventure did not stop Louis XIV from further expanding his national army, which reached 118,000 by 1672. He then initiated a war against the Dutch provinces, a six-year conflict that also drew in England and Sweden.

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Nine Years’ War (1672-78), was more successful in military terms and produced some important territorial gains, but it also proved costly. More than one billion livres was spent on this conflict. The last year of the Nine Years’ War alone cost 219 million livres.

During this war, domestic taxation in France reached its highest ever levels, yet at its peak taxes were supplying the government with just 160 million livres each year. Even after the peace of 1678, the expenditure of Louis’ government continued to exceed its income. By 1690, taxes were bringing in around 120-125 million livres per annum, which was barely enough to pay for the expenses of the royal court and its bureaucracy, let alone the other costs of government.

War of the Spanish Succession

The last of Louis XIV’s wars, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14), strained France’s finances to breaking point. It began when Louis XIV installed his grandson, Philip of Anjou, on the vacant Spanish throne, a move that threatened the imperial and trade interests of Britain, Austria and the Dutch. The War of the Spanish Succession became one of the first ‘world wars’, drawing in almost all of Europe’s significant powers. It lasted more than a decade, initiated heavy spending and left all of its major combatants with unprecedented levels of debt.

As with earlier conflicts, the royal government in France offset the costs of war by borrowing heavily and raising new taxes. Louis’ finance minister Nicolas Desmaretz sustained the government and the war effort by renegotiating or extending loans and introducing a national lottery. In 1710 Desmaretz introduced the dixième, a 10 percent tax on the earnings of all individuals (the clergy excepted). Yet even an income tax of this size did little to ease France’s deficit.

When Louis XIV died in 1715 France had spent decades living well beyond its means. According to a Compte Rendu drawn up by Desmaretz after the king’s death, France was carrying a national debt of two billion livres. The annual interest payments on this debt alone (165 million livres) were more than the government collected in taxes.

18th-century wars

France’s debt crisis might have been resolved if the 1700s had been a century of peace, prosperity and economic reform. But imperial wars continued to deplete the national treasury and prolong the national debt.

In 1740, the Hapsburg princess Maria Theresa, later the mother of Marie Antoinette, ascended to the throne of Austria, Hungary and other principalities in western Europe. Her coronation led to political and territorial disputes that evolved into the War of the Austrian Succession (1744-48). One of the main protagonists in this war was Louis XV, who argued that a woman could not occupy the Austrian throne, though secretly he hoped to expand French power at the expense of the Hapsburgs.

This war proved more difficult than Louis XV had expected. It required a much larger mobilisation of troops and was fought not only in Europe but in colonial North America and India. In territorial terms, the War of the Austrian Succession was a net loss for France. It also added 200 million livres to the national debt, a figure that would have been considerably higher had the government not widened the tax base in the mid-1740s.

“France’s governments were no less keen than the British to promote trade, but [the French] were the losers of the great imperial wars of mid-century [1700s]. The Seven Years War of 1756-63 stripped France of power in North America and ended a promising venture to gain power and trade in India. Even France’s successful but costly intervention on the side of the American revolutionaries in the 1770s did not break the American habit of trading with their mother-country – one of the mainstays of British industrial growth.”

David Andress, historian

War in North America

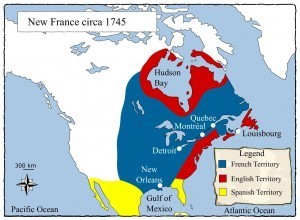

Even more costly to France was the Seven Years’ War of 1756-63. French involvement in this war began in North America, where France controlled vast tracts of land along the Mississippi and Ohio valleys. As French settlers and traders came into contact with British colonists resident on the east coast, there was tension and conflict over territory, hunting, fishing and the rights to fur-trapping.

In May 1754, a young British-American militia colonel named George Washington ambushed a French brigade in what is now Pennsylvania. The French retaliated and within a year both France and Britain had sent standing armies to America to protect their territory. By April 1756, France and Britain were also fighting in Europe, marking the start of the Seven Years’ War.

Like other imperial wars of the 18th century, the Seven Years’ War also drew in other European powers, including Austria, Russia, Spain, Prussia and the German kingdoms. The first three years of the conflict were successful for France, which secured some important victories and at one point planned an amphibious invasion of England. But by 1759 the tide of war had turned, in part because of France’s inability to fund its military operations. By late 1762 the French government was seeking peace, which was finalised by the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Economic losses

The Seven Years’ War produced little territorial or political change in Europe but it entailed significant losses for France, which was forced to surrender all its colonial possessions in North America. The outcome for the French treasury was even more disastrous.

France’s involvement in the Seven Years’ War cost around 1.3 billion livres. According to Brecher, the government raised 788 million livres from new loans, 386 million livres from new or extended taxes and 60 million livres by selling venal offices. Before the war Louis XV’s government was carrying around 1.2 billion livres in debt; by 1764 this had increased to 2.3 billion livres. This explosion in public debt was compounded by the loss of the American colonies, which meant millions of livres of foreign resources and trade were lost to the French economy.

A longer-term consequence of the Seven Years’ War was increased tensions between Great Britain and her own colonists in America, leading to the American Revolution between 1763 and 1783. France’s last pre-revolutionary war was the American Revolutionary War, which would cost the government a further 1.3 billion livres.

1. From the mid-1660s France fought a series of foreign and imperial wars that placed its economy under enormous strain and led to an explosion in national debt.

2. Louis XIV waged several wars – to consolidate and expand his own absolutism, to glorify himself as a military leader and to increase French power in Europe.

3. They included the War of Devolution (1667-68), the Nine Years’ War (1672-78) and the War of Spanish Succession (1701-14). They were funded by new or increased taxes and loans, yet still drained the national treasury.

4. His successor Louis XV also involved the nation in significant wars, most notably the War of the Austrian Succession (1744-48) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-63).

5. The last of these, the Seven Years’ War, saw France surrender all of its colonies in continental North America. It also left the nation with a national debt of around 2.3 billion livres.

Citation information

Title: ‘Imperial wars’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/imperial-wars/

Date published: October 11, 2019

Date updated: November 8, 2023

Date accessed: April 25, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.