On July 14th 1789, a crowd of several thousand people laid siege to the Bastille, a royal fortress on the eastern fringe of Paris. The Bastille had served as a royal armoury and a prison, though on this particular day it held few prisoners and was only lightly guarded. After a stand-off of several hours, the crowd gained access, overwhelmed the guards and arrested and murdered its governor. The fortress was claimed by the people and later demolished on the order of the new Paris Commune.

The capture and the fall of the Bastille was chiefly a symbolic victory. The French Revolution would have days of greater consequence, more political change and more bloody violence and destruction. Despite this, the events of July 14th have become a critical moment in history and a classic motif of people in revolution.

What was the Bastille?

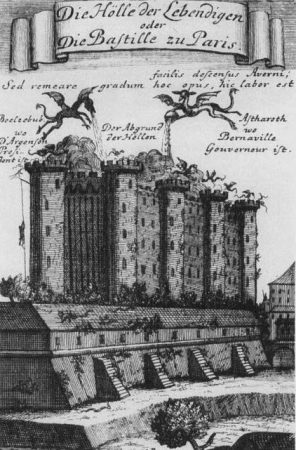

The real history of the Bastille is more mundane than its legend. The Bastille began life as a fortress, built in the mid to late 1300s to house a garrison of royal soldiers belonging to Charles V. The fortress and its garrison were installed to protect the eastern flanks of Paris from English raiders during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453).

By the early 1400s, the fortress had been expanded to become one of the largest structures in Paris, with its crenellated walls standing some 25 metres above the streets. Its tower loomed over Faubourg Saint-Antoine, a working-class district known for its rowdiness and occasional defiance.

A contingent of royal troops was permanently housed in the Bastille, both to defend the city walls and, if necessary, to keep order inside them. Over time, the building acquired the name Bastille, a generic French term for any fortress at the gate of a city.

A royal prison

By the reign of Louis XI (1461-1483), the Bastille had become a royal prison. It continued this function until the French Revolution, though by the late 1700s there were rarely more than 20 or 30 prisoners.

The majority of those detained in the Bastille were not common criminals but political prisoners or men held at the king’s pleasure. They tended to be rebellious or troublesome noblemen, aristocrats with large gambling debts, rogues caught in affairs with the wives of powerful men, religious heretics or critics of the church, seditious journalists and political pornographers. Some inmates were detained there by the courts, others by royal lettres de cachet.

Several notable philosophes and revolutionary figures spent time in the Bastille, including Voltaire (twice), Denis Diderot, Jacques Brissot, the playwright Pierre Beaumarchais, the pornographer Marquis de Sade and military commander Charles Dumouriez.

Indeed, a stint in the Bastille was useful for establishing one’s credentials as a writer or an intellectual. The Enlightenment economist André Morellet was detained there for slandering a princess, later writing “Once persecuted I would be better known… those six months in the Bastille would be an excellent recommendation and infallibly make my fortune”.

A symbol of royal tyranny

On the eve of revolution, the Bastille held very few prisoners. The frequency of lettres de cachet had declined through the 1780s – though Louis XVI‘s use of lettres de cachet against two magistrates of the Paris parlement (August 1787) and the Duke of Orleans (November 1787) triggered a wave of outrage.

The parlement itself issued a strongly worded remonstrance, criticising the king’s use of arbitrary power. The Paris press seethed about Louis’ actions, while writers like Honore Mirabeau and Emmanuel Sieyès condemned the lettres de cachet as an instrument of absolutist oppression. Sending rogues, fornicators and philanderers to the Bastille was one thing – but detaining magistrates for upholding the law and the general will was an act of tyranny.

In the eyes of the people of Paris, the Bastille fortress was a physical manifestation of this royal misuse of power.

Fears of counter-revolution

The attack on the Bastille followed a tumultuous six months. At Versailles, representatives of the Third Estate had defied the king to demand a constitution and form a national assembly. France looked to be transitioning toward constitutional monarchy, though many doubted the royal government would yield its power so easily.

In Paris, the working classes had endured months of bread shortages and high prices. Bread had peaked at 14.5 sous per loaf in February; it eased slightly during the spring but had returned to those levels by mid-July. Most Parisians were now spending at least three-quarters of their daily income to buy bread.

Louis XVI then made the first of two fateful decisions. Sometime around July 4th the king, probably on the advice of conservative ministers, ordered the assembly of royal troops at several critical locations: at Versailles, at Sèvres, at the Champ de Mars in south-west Paris and at Saint-Denis in the city’s north. Even those not given to suspicion could not miss the significance of this order: it appeared the king was planning to impose martial law to regain his power.

Parisians take action

Those fears intensified on July 11th when Louis dismissed his popular finance minister, Jacques Necker, and replaced him with the arch-conservative Joseph-François Foullon. Necker’s dismissal would trigger several days of insurrection in Paris.

On July 12th, a crowd of several thousand people gathered outside the Palais-Royal. They marched to the Tuileries, demanding Necker’s reinstatement. At the Tuileries, they were forced to scatter by a royal cavalry regiment, an incident later depicted as an intentional attack on harmless civilians.

The city’s military garrison, the French Guard, was called out to restore order but its soldiers refused to open fire on the people; in fact, many Guardsmen broke ranks and joined the insurrectionists. Royal officials were attacked or chased out of the city and 40 of the government’s 54 customs posts were looted and destroyed.

The people of Paris also spent July 12th and 13th gathering arms, in order to defend the city from an anticipated Royalist assault. Gun shops, small armouries and private collections were looted.

March on the Bastille

On the morning of July 14th, a crowd of several thousand people marched on the Hôtel des Invalides in western Paris. Though used chiefly as a military infirmary, the Invalides had a large store of rifles and several small artillery pieces in its basement. The mob entered the building and looted these weapons, while officers of nearby military regiments refused to intervene.

The invaders made off with around 30,000 rifles but found little gunpowder or shot with which to load them. The solution came from deserting guardsmen, who reported that 250 barrels of gunpowder had recently been stowed at the Bastille. The crowd then set off on a two-and-a-half mile march to the fortress, hauling several small cannons.

They arrived at around 11 in the morning and formed deputations to speak with the Marquis de Launay, the Bastille’s governor. De Launay was a colonel with a clean but unremarkable military record. He was an authoritarian who was disliked by his prisoners and soldiers alike (one chronicler later described him as a “proud and stupid despot”). In the colonel’s favour, he knew the Bastille well; his father had also been its governor and De Launay himself had been born within its walls.

The fortress was lightly guarded by around 120 soldiers, most old or infirm – but the Bastille’s strong high walls and its numerous artillery pieces made it almost unassailable, even for a crowd of several thousand people.

Tense negotiations

“Nothing is more terrible than the events at Paris between 12th and 15th July… cannon and armed force used against the Bastille… the Estates declaring the King’s ministers and the civil and military authorities to be responsible to the nation; and the King going on foot, without escort, to the Assembly, almost to apologise… this is how weakness, uncertainty and an imprudent violence will overturn the throne of Louis XVI.”

King Gustav of Sweden, 1789

Details of what transpired on the afternoon of July 14th are complex and confused. At first, the crowd seemed hopeful that De Launay, like the officers at the Invalides, would relent and simply grant them access to the Bastille’s stores. De Launay was not the compromising sort, however, and he had received official orders from the Hôtel de Ville to hold the Bastille at any cost.

Between late morning and mid-afternoon, the governor received deputations from the crowd. They pleaded with him to withdraw the fortress’s 18 cannons, pointed threateningly at the suburbs below, and to surrender the Bastille’s gunpowder to the people. De Launay agreed to the first but not the second.

At around 1.30PM a small group gained access to the Bastille courtyard through a half raised drawbridge. Fearing a full-scale attack, the governor ordered his soldiers to fire on the invaders. It was a fatal miscalculation that would cost De Launay his life.

The fortress falls

Hearing the garrison had opened fire on the people, crowds around the fortress swelled, and for three hours the Bastille came under siege. Two detachments of the French Guard defected and joined the people. The crowd was unable to operate the artillery pieces stolen from the Invalides so the involvement of mutinous soldiers was critical.

By late afternoon, the fortress was coming under cannon fire, much of it targeting the drawbridge. Convinced the situation was hopeless and fearing they would be slaughtered, De Launay’s officers urged him to surrender. He first tried bluff, threatening to ignite the gunpowder stores and blow much of eastern Paris into oblivion. When this did not work, De Launay surrendered the fortress at around five o’clock.

A large contingent then stormed the Bastille, arrested De Launay, fraternised with his soldiers and released the prisoners (there were seven in total, four of them counterfeiters). Those who entered the fortress, just under 1,000 in total, were later honoured with the title Vainqueurs de la Bastille (‘Vanquishers of the Bastille’).

Leaders ordered De Launay to be taken to the town hall to stand trial but on the way, he was seized by the crowd, choked and murdered. The cause of De Launay’s death is in dispute. A popular but unverified account suggests he was stabbed and beheaded by an unemployed baker wielding a small bread knife.

1. The Bastille was a large royal fortress located in the rowdy working-class neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Antoine, eastern Paris. It was erected in the 14th century to defend the city’s eastern approaches.

2. Later, the Bastille was used as a royal prison. It housed mainly political prisoners, libellistes and persons detained on royal lettres de cachet, rather than common criminals.

3. By the late 1780s, the Bastille had few prisoners, yet it stood as a symbol of royal absolutism. On July 14th the people of Paris ransacked the Invalides, stealing weapons, then marched on the Bastille to capture its supplies of gunpowder.

4. The Bastille’s governor, Marquis Bernard de Launay, received deputations from the crowd but refused to hand over the powder. On the afternoon of July 14th, the Bastille was stormed by the people and De Launay was arrested and eventually murdered.

5. Though the fall of the Bastille had few political ramifications, its loss represented a powerful narrative, a symbol of the ordinary people destroying an instrument of royal absolutism.

A Paris newspaper on the storming of the Bastille (1789)

An eyewitness account of the attack on the Bastille (1789)

A citizen recalls the taking of the Bastille (1789)

The British ambassador on the storming of the Bastille (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘The fall of the Bastille’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/fall-of-the-bastille/

Date published: October 2, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.