An émigré (French for ’emigrant’) was an individual who fled revolutionary France, either voluntarily or under threat of death or dispossession. The number of émigrés from the revolution is believed to have exceeded 100,000. These political refugees often set up and lived in expatriate communities abroad. Some cursed the revolution and worked to raise up armies to defeat it, though their efforts came to little. The new regime in France responded by seizing their wealth and promising arrest and execution should they ever return.

Who were the émigrés?

Contrary to popular opinion, not all émigrés were nobles – in fact, fewer than one in five possessed noble titles. More than half of all émigrés were members of the Third Estate, usually affluent bourgeoisie or those fleeing on religious grounds.

After fleeing, émigrés usually congregated in places beyond the reach of the revolutionaries, such as France’s outer provinces, other European kingdoms or across the channel in England. Most émigrés sought safety from the violence of the revolution but some also dreamed of organising an army to sweep into France, crush the revolution, liberate the king and restore the old order. Little came of their efforts and most counter-revolutionary émigrés were instead absorbed into foreign armies.

Within France, the new regime condemned émigrés as enemies of the revolution. Laws and ordinances were passed stripping these individuals and families of their titles, property and rights.

The first to flee

The first wave of emigrants left France as early as mid-1789. One of the earliest to leave was Charles Philippe, Count of Artois, a younger brother of the king. An arch-conservative who was considered “more Royalist than the king”, the Count of Artois was appalled by the events of the Estates General and the violence in Paris.

On July 17th, three days after the fall of the Bastille, Artois and a small group of courtiers left France for the Italian states. Some claimed he fled on advice from the king, who wanted to secure an alternative monarch, but the evidence for this is thin.

By September, the Count of Artois and his émigré cohort were based in Turin where they established a committee to organise and promote counter-revolution. Artois would spend the next two years trying to convince foreign governments to raise an army and intervene in France. He also planned to hire mercenaries to snatch the king and relocate him to a safer province, where Louis could re-form national government. Neither of these plans came to fruition.

Communities abroad

The flow of émigrés tended to accelerate after radical violence or some portentous development, such as the October Days in 1789 or the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790. By the summer of 1791, there were sizeable émigré communities in London, Vienna, Hamburg, Aix-la-Chapelle and Coblenz.

London was by far the largest of these, holding around 40,000 refugees from the revolution. Most of the London émigré community sought sanctuary and a return to high society; they attempted to recreate the salons and balls they attended back home. There were at least three French-language newspapers in London that catered for émigrés; the pages of these newspapers were filled with ridicule of the revolution and its leaders.

Many émigrés had a genuine sense of optimism about their situation. According to the radical Jacobin Choudieu, “emigration became a sort of fashion… Our women of fashion themselves encouraged this new sort of crusade and sent letters to those who were putting off going”. This optimism dwindled when the London émigré set, removed from their landed estates, businesses and income, began to run out of money.

Organising counter-revolution

Many émigrés on the continent were more interested in ending the revolution, in order to facilitate their return home and the reclamation of their wealth.

Young nobles and former military officers were at the forefront of counter-revolutionary émigré armies. One of the first significant forces was La Legion Noire (‘The Black Legion’), formed in late 1790 by André Riqueti, Viscount Mirabeau, younger brother of the National Assembly leader Honore Mirabeau. Riqueti was a bad-tempered drunk who, unlike his brother, was utterly opposed to the revolution. He managed to muster almost 1,000 men before selling the Black Legion to another émigré nobleman.

The German city of Coblenz became a gathering point for counter-revolutionary military activity, led by two of Louis XVI’s brothers, the Counts of Artois and Provence. These Bourbon royals wielded large sums of money furnished by other émigrés and the royal courts of Austria, Prussia and Spain – yet it was still not enough for the task at hand. They found recruiting large numbers of infantry soldiers difficult, not least because most émigrés expected to be officers rather than footsoldiers.

Once formed, émigré armies adopted an organisational structure that reflected the old society. Chateaubriand noted that one émigré army “was composed of nobles, grouped according to [their] province. At the very end of its days, the nobility was going back to its roots and to the roots of the monarchy, like an old man regressing to his childhood”.

“The French émigrés, led by Artois and Calonne, meant to use the Allies to recover their lost position in France, their manorial estates and their former perquisites of nobility. They cared little for Louis XVI, whom they regarded as a dupe of the Revolution… If they hoped to assure [his] personal safety and to uphold the dignity of royalty in general, they had no program for the internal rearrangement of France, and preferred if anything that the French monarchy should remain weakened by insoluble problems.”

Robert R. Palmer, historian

Problems and failures

Despite their determination, most of émigré armies were failures. They were costly to organise and supply, experienced problems with internal organisation and military discipline and were not well led.

The émigré armies reached their peak in mid-1792 when their numbers approached 25,000. In July 1792, émigré commanders persuaded the Duke of Brunswick to issue his famous manifesto, threatening the people of Paris with devastation if any harm came to the royal family.

The émigré armies were supremely confident of their ability but their first forays into battle proved disastrous. In late August 1792, a 16,000-strong émigré force laid siege to the French town of Thionville but failed to capture it, despite outnumbering the defenders four to one. At Longwy and Verdun, the émigrés achieved virtually nothing. At Valmy, they arrived after the battle had concluded.

Experienced Prussian and Austrian generals lost confidence in émigré battalions, finding the émigré leaders cocky and unbearable to work with.

The new regime responds

To add to these military failures, émigré leaders failed to understand the developments in France. The revolution, for all its faults, was unlikely to be crushed with by external force. As events in 1792 showed, external threats strengthened revolutionary nationalism and provoked radical violence.

The émigrés also believed that once their armies swept into France, the peasantry would welcome them with open arms and volunteer for military service. This was far from true. While many peasants in north-eastern France opposed the revolution, they had no desire to welcome back their former noble masters.

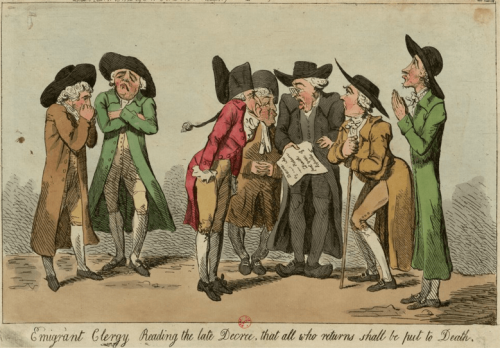

The capacity of the émigrés to threaten or undermine the new regime was negligible. This was not lost on the revolutionaries, who ridiculed the émigrés in both word and caricature (see picture above).

In Paris, the revolutionary government took action against the émigrés who threatened it. On November 9th 1791, the Legislative Assembly ordered all émigrés to return to France “on pain of death” (though this law was vetoed by Louis XVI three days later). On February 9th 1792 the Assembly passed another decree, declaring the property of émigrés to be bien nationaux (‘national goods’).

The sequestration of émigré property continued through the summer of 1792. On October 25th, the newly formed National Convention went further, banning all émigrés from France and promising them an immediate visit to the guillotine should they ever return.

1. The émigrés were those who fled the revolution, either for security, safety or to organise counter-revolution. There were more than 100,000 émigrés between 1789 and 1794.

2. Only a small proportion of émigrés were nobles, in fact, most belonged to the Third Estate. They went into exile in France’s outer provinces, other European kingdoms or across the channel in London.

3. London had the largest émigré population, housing around 40,000 refugees from revolutionary France. The émigrés there attempted to recreate the society and culture of the Ancien Régime.

4. Other émigrés, particularly those in Coblenz, attempted to organise counter-revolutionary armies. These armies were beset with problems, however, and their early military ventures ranged from ineffective to disastrous.

5. The new regime implemented harsh penalties against the émigrés, ordering the seizure and sale of their properties, banning them from re-entering France and promising the death penalty if they returned.

Citation information

Title: ‘The emigres’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/emigres/

Date published: September 14, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: April 18, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.