Information and resources on this page are © Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be copied, republished or redistributed without the express permission of Alpha History. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

Category Archives: French Revolution

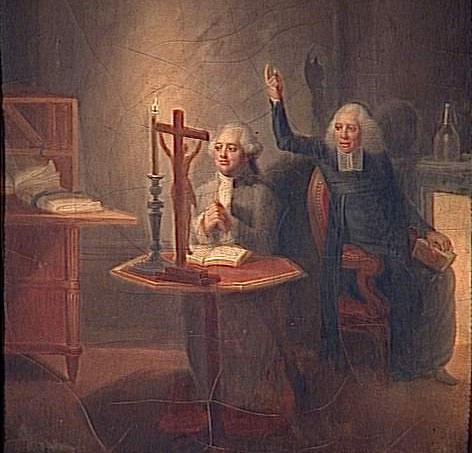

The Cult of the Supreme Being

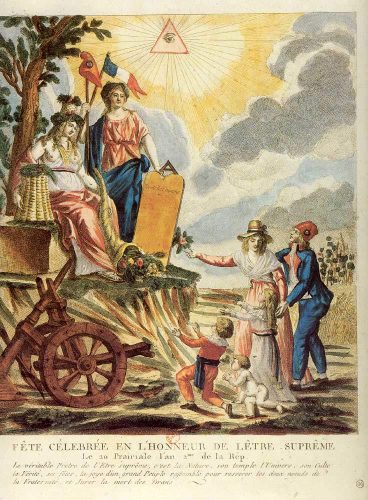

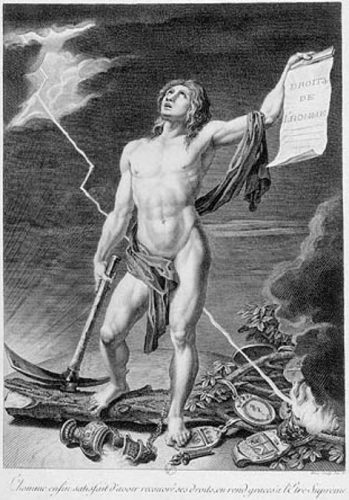

The Cult of the Supreme Being, created in May 1794, was an ambitious attempt to construct a national religion based on patriotism, republican values and deism (the Enlightenment theory that God existed but did not interfere in the affairs of men). For its creator, Maximilien Robespierre, the Supreme Being movement was intended to educate and enlighten the people about the fundamental connections between religion, morality, republican government and citizenship. Few came to share this enthusiasm and the Cult of the Supreme Being lasted only as long as its benefactor, dying with Robespierre in July 1794.

The Cult of Reason

The Supreme Being movement was not the revolution’s first attempt to replace Catholicism. In 1793, radical journalist Jacques Hébert and his followers founded the Cult of Reason, a group dedicated to celebrating liberty, rationalism, empirical truth and other Enlightenment values.

The Cult of Reason was, in essence, an atheist church. It embraced the trappings and practices of religion, such as congregational services, symbolism and worship – but its advocates denied the existence of any deity or supernatural forces. The Cult of Reason became popular among intellectuals and sans-culottes alike.

From mid-1793, the Jacobin-dominated Convention gave tacit approval to the Cult of Reason. The culmination of the movement was the Festival of Reason, held in the Notre Dame cathedral on November 10th 1793.

Formation

The Cult of Reason’s atheism outraged the French Revolution’s arch puritan, Maximilien Robespierre. Robespierre was greatly concerned about public morality. France could never have a virtuous and effective government, he claimed, until the people themselves were taught morality and virtue.

Robespierre believed the revolutionary government must lead this process by engaging “in the art of enlightening them [the people] and making them better”. This could not be achieved with atheism, he thought, only through an inclusive cult that combined worship of the divine creator with patriotic ceremonies.

On 18 Floreal (May 7th), Robespierre rose in the Convention and delivered one of his most famous orations, speaking of the revolution, its achievements and the pivotal connection between virtue and terror. At Robespierre’s behest, the Convention passed a Decree on the Supreme Being (1794). This decree acknowledged the existence of a Supreme Being and legislated for its worship:

“1. The French people recognise the existence of the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul.

2. They recognise that the worship worthy of the Supreme Being is the practice of the duties of man.

3. They place in the first rank of these duties [the obligation] to detest bad faith and tyranny, to punish tyrants and traitors, to rescue the unfortunate, to respect the weak, to defend the oppressed, [and] to do to others all the good that one can and not to be unjust toward anyone.

4. Festivals shall be established to remind man of the thought of the Divinity and of the dignity of his being.

5. They shall take their names from the glorious events of our revolution, from the virtues most dear and most useful to man and from the great benefactions of nature.

6. The French Republic shall celebrate every year the festivals of July 14th 1789, August 10th 1792, January 21st 1793, and May 31st 1793.

7. It shall celebrate on the days of decadi festivals to the Supreme Being and to nature, to the human race, to the French people, to the benefactors of humanity, to the martyrs of liberty, to liberty and equality, to the Republic….”

“A substantial section of the speech on 18 Floreal was devoted to a condemnation of atheism. This, Robespierre argued, dissolved the bonds of society. It led people to believe that the fate of all, good as well as wicked, was decided by blind chance. Society was left at the mercy of the strongest and the cleverest. By contrast, religion reinforced the social bonds by differentiating between the regenerate and the unregenerate. It is not altogether clear how Robespierre saw this working.”

Colin Haydon, historian

Robespierre’s motives

Many historians have pondered whether the Supreme Being was a genuine reflection of Robespierre’s personal religious beliefs, or a clever attempt to use religion to enhance his own power. It may have been both.

There is certainly evidence that Robespierre believed in God and the immortality of the soul. Like other Jacobins, he had been a barbed critic of the church, but his attacks were almost always confined to the higher clergy. Robespierre supported the Civil Constitution of the Clergy because it stripped the church of its economic privileges and removed prelates from political power but he had often defended parish priests and friars.

Robespierre’s Supreme Being was certainly not a direct replacement of the Catholic God. The Supreme Being was a deistic Enlightenment entity, a wise and rational God who had created the world and set it in motion according to natural laws. The best way to regenerate society and draw closer to this Supreme Being was to study, uphold and honour these natural laws.

Festival in Paris

The National Convention’s May decree specified 20 Prairial, Year II (June 8th 1794) as the first Festival of the Supreme Being. It ordered the artist Jacques-Louis David to oversee the organisation of this festival.

The result was a tightly coordinated and choreographed series of marches and ceremonies. According to contemporary reports, the Festival of the Supreme Being in Paris had all the micromanagement, discipline and emotional fanfare of a Nazi rally. It began with speeches and a symbolic ceremony in the Tuileries garden, where a statue representing atheism was set alight.

The participants and crowd then proceeded to the Champ de Mars. There they found an enormous mountain, skilfully constructed by David out of timber and plaster, bedecked with rocks, shrubs and flowers, and illuminated with lights and mirrors. The mountain itself was a symbol of collective strength, of natural power, of mankind’s ascendancy and elevation toward heaven – and, of course, the Montagnard faction of the Convention.

Robespierre, dressed in a grand blue coat and gold trousers, led the deputies of the Convention to the top of the artificial mountain while the crowd looked on from below. Overlooked by a statue of Hercules atop a Doric column, the deputies recited oaths and sang verses of Le Marseillaise and other revolutionary anthems.

Public responses

Robespierre’s critics watched the Festival scornfully, noting how the ‘Incorruptible’ had placed himself in positions of great prominence. Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, an ageing politician once allied with Georges Danton, was not impressed by Robespierre’s speeches and histrionics. “Look at the bugger,” said Thuriot. “It’s not enough for him to be in charge, he has to be God”.

Most ordinary Parisians, however, responded well to the Festival. By 1794 they had grown accustomed to revolutionary festivals. They enjoyed the pomp and pageantry of these events, the respite from daily work and political conflict, the opportunity to remember what had been gained rather than arguing over what had not been achieved.

Some observers believed the Festival of the Supreme Being was a grander, more significant celebration than its predecessors. Jacobin newspapers, like the Journal de la Montagne, gushed about it, saying “this day consecrated to the Supreme Being will be the finest day in the life of the virtuous man… a simple ceremony, majestic and truly worthy of the eternal author of Nature”. Some who attended the Festival believed it marked an end to the Reign of Terror and revolutionary violence – a flawed hope, as Huet explains:

“One observer reported: “After the ceremony [the people] went to their homes with the tranquility and the propriety of a nation truly free. Today they have rejoiced at the change of place of the guillotine. I have heard a great number of citizens say: ‘With this change, the sword of the law will lose none of its effect, and we can enjoy a promenade which will become the finest in Europe’. According to Michelet, other people believed that the new cult also signaled an end to the executions. But far from signifying [this] it preceded, by just a few hours, the onset of what has been called the Great Terror. Indeed, two days after the Festival of the Supreme Being, the Convention voted the Law of 22 Prairial, submitted by Couthon (and generally thought to have been inspired by Robespierre).”

Failure and demise

For all its hope and grandeur, the Cult of the Supreme Being lasted only as long as Robespierre – which, as it turned out, was just another six weeks.

The contrived religious movement failed to capture the public imagination or win any natural support. Its ideas about creation, worship, personal conduct and destiny were vague and poorly explained. The new religion needed a charismatic and convincing leader to attract supporters and articulate a vision, qualities that Robespierre did not possess.

More significantly, Robespierre’s decision to position himself at the head of the Supreme Being cult only hardened his opposition. Several deputies who attended the Festival believed Robespierre showed signs of delusions and megalomania. These concerns contributed to the push to dispose of Robespierre in late July. After his execution, the Thermidorian Convention distanced itself from the Supreme Being movement, which without its creator and sponsor soon died a natural death.

1. The Cult of the Supreme Being was an artificial religion, developed by Robespierre and given formal status by the National Convention in May 1794.

2. In Robespierre’s mind, the Supreme Being was a deist god who created the world according to natural laws. The purpose of the cult was to educate the people and teach them morality and virtue.

3. The high point of the Supreme Being movement was a Festival, held in Paris and other locations in early June. It was marked by symbolism, pageantry and speeches celebrating the Enlightenment and regeneration.

4. The Paris Festival featured a gigantic artificial mountain on the Champ de Mars and featured speeches and gestures from Robespierre, who at his insistence played a leading role.

5. The Festival itself was popular with the people, however, the Cult of the Supreme Being failed to take hold, and Robespierre’s central role only increased his unpopularity among other deputies of the Convention.

Decree establishing the Cult of the Supreme Being (1794)

Witnesses to the Festival of the Supreme Being (1794)

Robespierre pays homage to the Supreme Being (1794)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Cult of the Supreme Being’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/cult-of-the-supreme-being/

Date published: September 15, 2019

Date updated: November 11, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

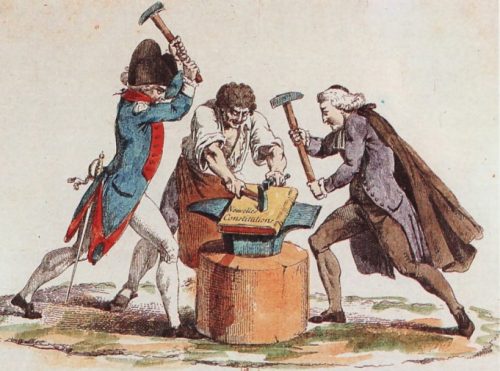

The Law of the Maximum

The Law of the Maximum, passed in September 1793, was an attempt by the National Convention to ease the food crisis by fixing a maximum limit for prices. This followed months of agitation and political unrest, culminating in the expulsion of the Girondins from the Convention. The Law of the Maximum was well received by the sans-culottes of Paris but it failed to improve their condition, and in some respects only worsened the problems of food production and distribution.

Background

By 1793, wages, food prices and living conditions in Paris had scarcely improved since the conditions that led to the insurrection of 1789France’s war with Europe had reduced imports and exports and disrupted internal trade. Mobilisation for war and events in the provinces had also disrupted agricultural production.

In the nation’s cities and towns, the introduction of paper assignats had caused severe inflation. The price of a four-pound bread loaf had fallen to eight sous in 1791 – but by 1793 it was up to back up to 12 sous. The cost of other foodstuffs, particularly wine and meat, had also increased markedly. Between 1791 and 1793, inflation pushed food prices up by 90 percent while wages increased by around 80 percent in the same period.

By early 1793 the sans-culottes of Paris were urging the National Convention to resolve food shortages and do something about exorbitant prices.

The Enragés

Leading this campaign were the Enragés (French for ‘enraged ones’). The Enragés were not a political club but a cluster of individuals who, as their name suggests, raged against anyone they believed was profiting from high food prices. The Enragés were, in essence, class levellers who wanted a society of economic equality, the French Revolution’s equivalent of Marxist socialists.

The most prominent member of the Enragés was Jacques Roux, a Catholic clergyman turned radical activist (he was later dubbed the ‘Red Priest’). Roux was politically active in the Paris Commune and the sections but he also worked tirelessly with the poor, trying to locate and distribute food.

Roux’s rousing speeches had little impact on a Convention now dominated by the Jacobins but they were well received on the streets of Paris. In February 1793, the capital was struck by a series of market riots. These riots were started almost exclusively by women protesting against the high price of bread, sugar, coffee, even soap. By late February the riots had been joined by men, threatening violence against bakers and grocers who refused to lower their prices.

Food shortages politicised

The food riots continued in early March when bread shortages began to ease. Between March and June 1793, the Convention was largely occupied by matters of war and a power struggle between the Girondin and Montagnard factions. Radical journalists aligned with the Jacobins began to shift the blame for high food prices to the Girondins. Public perception associated Girondinist deputies with the provinces, with business interests and the bourgeoisie – all this made them convenient scapegoats for the problems of food supply.

At the start of May 1793, the Jacobins in Paris began to side with the sans-culottes over food policy. It was a calculated shift, designed to gain public support and finish off the Girondins for good. Maximilien Robespierre, who had previously shown little sympathy for food rioters or hungry sans-culottes, began to thunder against grain hoarders, price speculators and profiteers.

On May 4th, the Convention took its first steps toward price controls, fixing the price of wheat and flour. Girondins opposed any price controls; they believed that food supplies would soon increase and prices would eventually fall. “These words ‘hoarders’ and ‘monopolies'”, the Girondin deputy Jacques Creuzé-Latouche told the Convention, “are only the dangerous visions of foolish persons and ignorant women”.

The Jacobins in charge

Politically, the leftward shift in Jacobin economic policy had the desired effect. The sans-culottes began to side with the Jacobins and the Montagnards, demanding the removal of the hated Girondins from the Convention. Public pressure continued to build through May 1793, eventually culminating in the journée of May 31st and the expulsion of Girondin deputies on June 2nd.

This was clearly a victory for the Jacobins and the Montagnards in the Convention – but now, they alone were responsible for economic conditions in Paris. There could be no scapegoats and no more blame-shifting.

On June 25th 1793 Jacques Roux delivered a rousing speech to the National Convention, later dubbed the ‘Manifesto of the Enragés‘. In this speech, Roux challenged the Montagnard deputies to take strong action against anyone who monopolised food sales and profited from high prices:

“One hundred times this hall has rung with the crimes of egoists and knaves. You have always promised to strike the bloodsuckers of the people. The constitutional act is going to be presented to the sovereign for sanction. Have you prohibited price speculation [in the new constitution]? No. Have you called for the death penalty against monopolists? No. Have you determined what freedom of commerce consists of? No. Have you forbidden the sale of minted money? No. Well then, we say to you that you haven’t done everything for the happiness of the people.”

Roux silenced

Inc

Rather than heeding Roux’s challenge, the Jacobin machine moved to silence him. In L’Ami du Peuple, Marat condemned Roux as a troublemaker and a “false prices”. Robespierre and his allies followed suit in the Convention. By late August, Roux was languishing in a prison cell on charges that were probably fabricated.

Roux’s disappearance from the political scene did not silence the sans-culottes, who continued to demand action from the Convention. “People are suffering”, said a petition to the Convention in September 1793. “Nobility is crushed but it breathes still in a new elite, merchants and food speculators (the two words are synonymous). Why should the sans-culottes give their blood for the fatherland while the rich get richer? Why should they not rise up and cut off the heads of the rich, as they have done to the courtiers of the king? This will happen unless you fix the maximum.”

Prices fixed

“This General Maximum set prices at the local levels of 1790 plus one third, but undervalued transport costs drastically, encouraging producers to bring their goods to the nearest rather than the neediest market… Across vast swathes of the country, food was unavailable at the Maximum price and required recourse to the black market or payment of a supplemental fee.”

David Andress, historian

On September 29th, just days after this petition, the Convention responded by passing the Law of the Maximum, also known as the General Maximum. This radical legislation imposed a maximum price on dozens of essential goods, mostly food items.

Among the commodities price-capped by the Maximum were “fresh meat, salt meat and bacon, butter, sweet oil, cattle, salt fish, wine, brandy, vinegar, cider, beer, firewood, charcoal, coal, candles, lamp oil, salt, soda, sugar, honey, white paper, hides, iron, cast iron, lead, steel, copper, hemp, linens, woollens, stuffs, canvases, the raw materials used for fabrics, wooden shoes, shoes, turnips and rapeseed, soap, potash and tobacco.”

Under the Maximum, merchants were required by law to display a full list of their maximum prices, posted in a window or outside their store. If any of these prices exceeded the legislated maximum, the general public could inform the city authorities. Merchants who breached the law were fined double the value of each overpriced item. Curiously, the fine was paid to the informer, not the state. The General Maximum also placed a cap on wages.

Economic effects

The move to fix prices and wages was based on good intentions but was economically disastrous, as artificial price controls tend to be.

The limitations imposed by the Maximum discouraged farmers and producers. They began producing less or hoarding what they did produce, rather than selling food below its real value. Less food made its way into the towns and cities, which only exacerbated the shortages there.

Caught in the middle were the urban retailers and petit bourgeoisie – shopkeepers, butchers, bakers and market stall holders – most of whom survived on the slimmest of margins. According to economist Henry Bourne, “the honest merchant who became the victim of the [maximum price] law”, while the disreputable and corrupt exploited it. “The butcher in weighing meats added more scraps than before… other shopkeepers sold second-rate goods at the maximum… The common people complained that they were buying pear juice for wine, the oil of poppies for olive oil, ashes for pepper, and starch for sugar.”

A thriving black market also emerged: many were prepared to risk their lives and freedom by trading illegally with those prepared to pay above the prescribed maximum.

1. The Law of the Maximum was an attempt by the National Convention to fix price levels, in order to appease the sans-culottes and their supporters in the Jacobin movement.

2. By early 1793 food prices had increased again, prompting a series of bread riots in Paris in February and March, and the emergence of economic radicals known as the Enragés.

3. The Jacobins, seeking the political upper hand over the Girondins, began to side with the sans-culottes. On May 4th 1793 the Convention imposed maximum prices on wheat and flour.

4. Continued pressure from Jacques Roux, the Jacobins and the sans-culottes led to the passing of the General Maximum in late September, which fixed wages and prices on a range of essential goods.

5. Rather than solving the problem of food availability and prices, the Maximum made it worse by discouraging farmers and reducing the amount of food coming into towns and cities.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Law of the Maximum’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/law-of-the-maximum/

Date published: September 30, 2019

Date updated: November 16, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

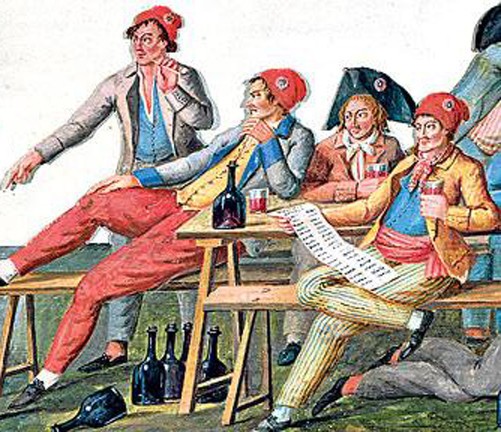

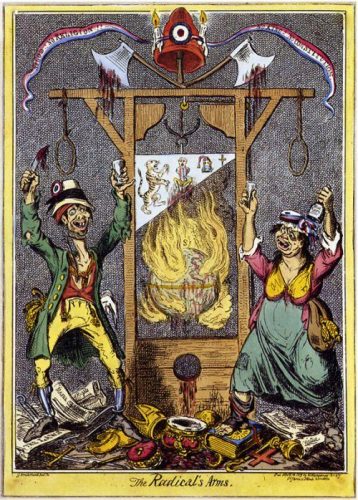

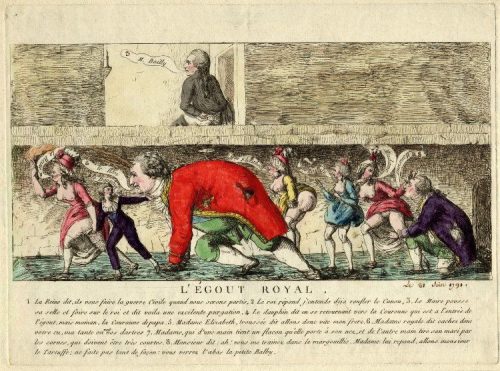

The sans-culottes

The sans-culottes is a term describing the working classes of Paris who participated in the great journées of the French Revolution. Identifiable by their clothing, their radical political views and their frequent use of violence and intimidation, the sans-culottes became the face of the radical revolution of the 1790s. There remains, however, considerable debate about who the sans-culottes actually were.

Who were the sans-culottes?

Chroniclers, novelists and historians have given us many depictions of the Parisian working class. Some have fallen into stereotype while other depictions remain hotly debated.

To some, the sans-culottes were an amorphous but brutal mob, seething with discontent, susceptible to rumour and gossip, hell-bent on achieving their aims with violence. Other historians, like George Rudé and Albert Soboul, have deconstructed the identities, motives and methods of the sans-culottes and found greater complexity.

Whatever the interpretation of the sans-culottes and their motives, their impact on the revolution, particularly between 1792 and 1794, is undeniable.

Etymology

The term sans-culottes is French for ‘without britches’. It was initially a humorous term, referring to a young man caught in an embarrassing situation with a woman.

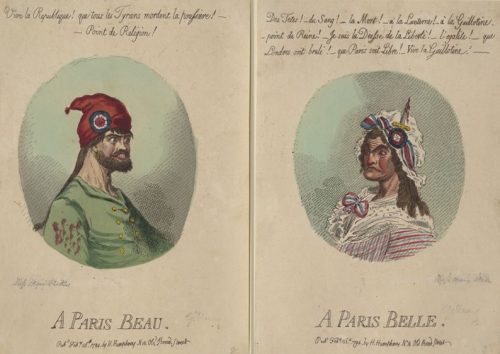

Sans-culottes first appeared in a political context in 1790, to describe townsmen who wore pantaloons (long trousers) instead of the knee-length britches favoured by the nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie. It was first used in royalist newspapers, to ridicule working class members of the Jacobin club.

Before long the phrase sans-culottes was in common use, describing urban workers, artisans or small businessmen, especially those who supported the revolution. Later, the popular perception of a sans-culotte was a political radical from the working classes and sections of Paris.

Composition

The sans-culottes were uniformly working-class: most either laboured for wages or ran their own small stores or businesses. They lived in the poorer suburbs of Paris, most notably Faubourg Saint-Antoine and Faubourg Saint-Michel in the city’s east.

A minority of sans-culottes were politically active, at least in an organised sense. They were most commonly found in the 48 sectional assemblies that made up the Paris Commune. Of the 1,361 deputies who sat in these assemblies in 1793-94, more than two-thirds were tradesmen or shopkeepers. Others attended the sectional assemblies as spectators or hecklers. Some also attended meetings of the political clubs – most notably the Society of Cordeliers, which was open to all, and later the Jacobins.

The majority of sans-culottes, however, remained outside organised politics. They obtained their political news from the inflammatory press and secondhand reports, which of course made them susceptible to rumour and conspiracy theories.

The sans-culottes could also be roused to action by orators and propagandists. An example of this was the journée of May 31st 1793, which culminated in the expulsion of Girondin deputies from the National Convention.

Intimidation and violence

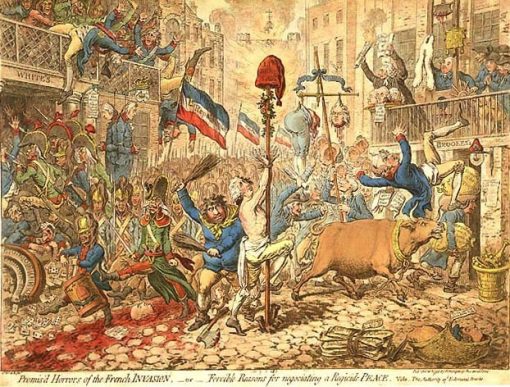

The hallmark of the sans-culottes was their capacity for forcing change with threats and violence. Working-class mobs were involved in just about every significant journée in revolutionary Paris. They laid siege to the house and factory of Réveillon in April 1789. Three months later they attacked the Bastille, butchered its governor and dismembered the royal minister Joseph-François Foullon.

In October 1789, the sans-culottes, many of them women, marched on Versailles, menaced the royal family and forced the king to return to Paris. They massed on the Champ de Mars in July 1791 to sign Republican petitions, dozens dying from the gunfire of the National Guard.

In August 1792, Parisian sans-culottes invaded the Tuileries palace alongside Republican troops and, once inside, participated in the slaughter of the Swiss garrison. On the same day, they surrounded the Legislative Assembly and coerced it into suspending the monarchy. The following month (September 1792), sans-culottes raided the prisons of Paris and ‘cleansed’ them of counter-revolutionaries and traitors, one of the bloodiest incidents of the entire revolution.

Political aims

What were the political aims of the sans-culottes? For the most part, they were democratic, egalitarian and wanted price controls on food and essential commodities. Beyond that, their aims are unclear and open to conjecture.

Some historians have categorised sans-culottism as a petit bourgeois movement, dominated by tradesmen and small business owners. Gwyn Williams researched 450 influential sans-culottes leaders and found that almost two-thirds were artisans and shopkeepers, while only one in ten was a wage earner. They were not anti-capitalist, Williams contends, nor were they opposed to wealth or private property, only its concentration in the hands of a privileged few.

In contrast, the socialist historian Albert Soboul sees the sans-culottes as class warriors. They were ‘Marxists before Marx’ who sought to destroy the aristocracy and remake the world along socialist lines. Revisionists like Alfred Cobban reject the suggestion that the sans-culottes were themselves a social class or even a homogenous group. There was too much diversity in their ranks, their motives were often unclear, and they usually responded to events rather than leading or creating them.

The sans-culotte cult grows

Whatever the realities of the sans-culottes movement, it was undoubtedly coloured by idealism and propaganda.

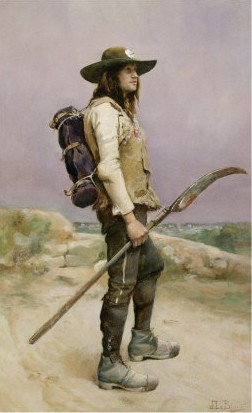

By the autumn of 1793, the Jacobins and their supporters were beginning to embrace a cult of democracy and egalitarianism. At the centre of this were the sans-culottes, who were celebrated as working-class heroes and the political vanguard of the revolution. Propagandists painted a stereotype of the typical sans-culotte: hardworking and humble, politically alert, watchful and prepared, always ready to take up arms to defend the revolution.

A well known epigram, published by Antoine-François Momoro in 1793, asked and answered the question “What is a sans-culotte?”:

“A sans-culotte, you rogues? He is someone who always goes about on foot. [He] has not got the millions you would all like to have… [He] has no chateaux, no valets to wait on him… He is useful because he knows how to till a field, to forge iron, to use a saw… and to spill his blood to the last drop for the safety of the Republic… In the evening he goes to the assembly of his Section, not powdered and perfumed and nattily booted, in the hope of being noticed by the female citizens in the galleries, but ready to support sound proposals with all his might, and ready to pulverise those which come from the despised faction of politicians. Finally, a sans-culotte always has his sabre well-sharpened, ready to cut off the ears of all opponents of the Revolution.”

The ‘purest revolutionary’

As this stereotype took hold, the sans-culotte was hailed as the backbone of the revolution and the purest type of revolutionary. Whether by choice or necessity for self-preservation, many in Paris began to actively mimic the sans-culottes.

Those who wished to demonstrate their support of the revolution, whatever their own class, began dress in the garb of the sans-culotte: long-legged trousers, a short-tailed carmagnole coat and the bonnet rouge or ‘liberty cap’. Formal modes of address like “Monsieur”, “Madame” and “Mademoiselle” were abandoned in favour of the more egalitarian and patriotic “Citoyen” and “Citoyenne”. Those who refused to embrace this adoration and mimicry were open to suspicion.

While perceptions of the sans-culottes shaped revolutionary culture, by late 1793, the political influence of the sans-culottes was beginning to wane. The National Convention was now dominated by Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins, who moved to centralise their power and unfurl the Reign of Terror. This involved some curtailment of sans-culotte political activity.

In September, the government limited sectional assemblies to a maximum of two five-hour meetings per week. The Convention also nobbled the autonomy of the Paris Commune, the other institutional beacon for Parisian radicals. There were attempts to mobilise the sans-culottes in 1794 and 1795 but these lacked the impact of earlier journées.

“The sans-culottes often estimated a person’s worth by appearance, deducing character from costume and political convictions from character; everything that jarred their sense of equality was suspect of being ‘aristocratic’. It was difficult, therefore, for any person of the old regime to find favour in their eyes, even when there was no specific charge against him. ‘For such men are incapable of bringing themselves to the heights of our revolution; their hearts are always full of pride and we shall never forget their former grandeur and their domination over us.”

Albert Soboul, historian

1. The sans-culottes were the working class people of Paris, so named because they wore long trousers (pantaloons) rather than the knee breeches favoured by the aristocracy.

2. The leaders of the Parisian sans-culottes were found in the sectional assemblies and the Commune, particularly after August 1792. Most sans-culottes themselves, however, were not involved in organised political groups.

3. Broadly speaking, the sans-culottes wanted a democratic government with universal suffrage, as well as price controls on food and other essential goods. Their aims beyond that are a matter of debate.

4. The sans-culottes are best known for their use of mob violence and intimidation to bring about political change. They were involved in almost all of the violent journées in Paris during the early 1790s.

5. During the radical period in 1793-94, propaganda and popular culture hailed the sans-culottes as the humble vanguard of the French Revolution. Their political impact, however, was negated by the growing centralisation of Jacobin power.

Citation information

Title: ‘Sans-culottes’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/sans-culottes/

Date published: September 24, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

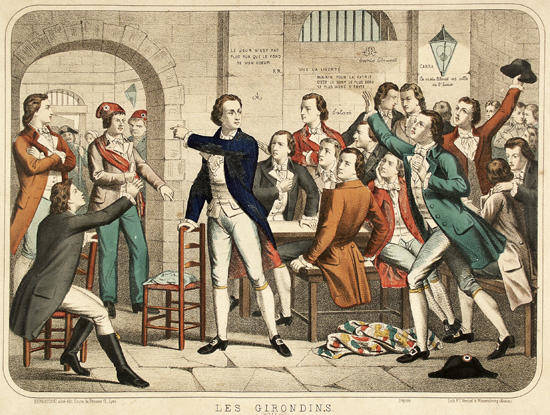

The Girondins and Montagnards

The Girondins and Montagnards were two powerful factions in the National Convention from its creation in September 1792 until the middle of the following year. These factions symbolised the competing perspectives of the French Revolution during this period. Girondin deputies were moderates with a national view while the Montagnards were radicals dominated by Parisian interests. Eventually, the tension between the two groups turned to conflict, leaving one victorious and the other expelled from the Convention.

Summary

Like politicians everywhere, France’s revolutionary legislators held different views on ideology, class, economics, provincial issues and other issues. This diversity was evident in the revolution’s first legislature, the National Constituent Assembly, where most radical deputies sat to the left of the president’s chair and moderate and conservative deputies sat to the right (a practice that gave rise to the modern terms “left-wing” and “right-wing”).

Similar alignments continued in the Legislative Assembly (October 1791-September 1792). Its replacement body, the National Convention, developed two distinct factions called the Girondins and the Montagnards. While these groups lacked the formal organisation and discipline of political parties, they were unified enough to vote in blocs and spend months disagreeing over policy.

This bickering came to a head in early June 1793 when the Montagnards, under pressure from the National Guard and the sans-culottes of Paris, expelled Girondin deputies from the Convention. Most Girondins were arrested or forced into exile. Of those who remained, few would survive the Reign of Terror.

Evolution of the Girdonins

The Girondinist faction took shape in the Legislative Assembly in the second half of 1791. It grew around the figure of Jacques-Pierre Brissot, a Republican lawyer and influential speaker in the Jacobin club. Brissot was a popular figure and a number of like-minded deputies gravitated toward him.

This faction became known as the Brissotins or Girondins, so named because many members were from Bordeaux in the Girdone département. Their numbers in the Assembly grew and their leaders and policies also came to attract many supporters outside it. High profile Girondins included economist and businessman Jean-Marie Roland and his salonnière wife Madame Roland, noted politician and philosopher the Marquis de Condorcet, future Paris mayor Jérôme Pétion, radical journalist Nicolas de Bonneville and the powerful orator Pierre Vergniaud.

Prominent Girondins not only shared the benches in the Legislative Assembly and National Convention, they also met regularly at Roland’s home and other residences to discuss events in the Convention, politics and strategy.

“In the [National] Constituent Assembly, Girondins and Montagnards were indistinguishable. The Legislative Assembly was a period of gestation. Embryos of the two ‘parties’ formed in late 1791 and early 1792, in debates over peace or war, and were born after painful labour during the seven weeks following August 10th 1792. It was then the Montagnards took control of the Paris Commune and Jacobins. The Montagnards also had the support of the Paris sections (electoral district assemblies) but their reliance on the sections meant they had to cosy up to radical agitators. Montagnards dominated the delegation elected by Paris to the Convention.”

Michael Kennedy, historian

Girondinist positions

At their peak, the Girondins had about 200 deputies in the National Convention. Leadership and policy-making were provided by a clique of prominent deputies dubbed the ‘inner sixty’. By late 1792, the Girondinist faction was most commonly perceived as being intellectual, measured, cautious and faithful to the revolution.

Politically, the Girondins were moderate Republicans. They initiated a revolutionary war in April 1792, hoping to pre-empt foreign aggression, win public support, militarise the revolution and export it beyond the walls of Paris. Their ideal society was free, capitalist and meritocratic with personal liberty protected by the rule of law.

Most significantly, the Girondins wanted a national government chosen by all citizens and representative of all citizens – not just the people of Paris. They distrusted the radicalism of Paris and believed the sections, the Commune and the <em>sans-culottes exerted too much political influence. According to Brissot, these groups were “disorganisers who want everything levelled”.

Le Montagne

The Montagnards were not clearly recognisable as a faction until the National Convention. The terms Montagnards (‘mountain people’) or La Montagne (‘The Mountain’) were first used during sessions of the Legislative Assembly but were not in common use until 1793.

The Montagnards referred to those who occupied the higher benches in both the Jacobin club and the national legislature. Those who sat on these high benches were generally more radical in their ideology and their policies, while those who sat further down were usually more moderate.

Unlike the Girondins, who enjoyed considerable support in the provinces, the Montagnards drew much of their support from Paris. Of the 24 Parisian deputies in the National Convention, 21 sat with the Montagnard faction.

The Plain

The National Convention also contained a third grouping. Known as Le Plaine (‘The Plain’) or Le Marais (‘The Marsh’ or ‘The Swamp’), this mass of deputies occupied the floor space and lower benches of the Convention.

The Plain enjoyed an absolute majority in the Convention, boasting 389 of its 749 deputies in 1792. Because of this, no legislation or resolution could pass the Convention without the support of their deputies. Unlike the Montagnards and Girondinists, however, the Plain was filled with shiftless and uncommitted voters. Its deputies were effectively swinging voters, not wedded to a particular ideology or outlook. The best way to win the support of the Plain was with convincing oratory. This made speech-making a critical skill in the National Convention.

The Plain was generally moderate in the first months of the Convention, siding with the Girondins on most issues. As the revolution progressed and radicalised in 1793, many Plain deputies began to vote with the Montagnards.

Conflict intensifies

The conflict between the Girondins and Montagnards came to a head in the spring of 1793. The catalyst for this was the trial and guillotining of Louis XVI.

In January 1793, the National Convention found the king guilty and voted for his execution. Many Girondin deputies, fearing the king had been judged by Paris rather than the nation as a whole, sought an appel au peuple (‘appeal to the people’) – in effect, a referendum on whether the king should die. This motion was defeated in the Convention, which helped undermine Girondin authority. Among the Montagnards and the Jacobins, the Girondin appel au peuple was denounced as a royalist plot to save the king’s life.

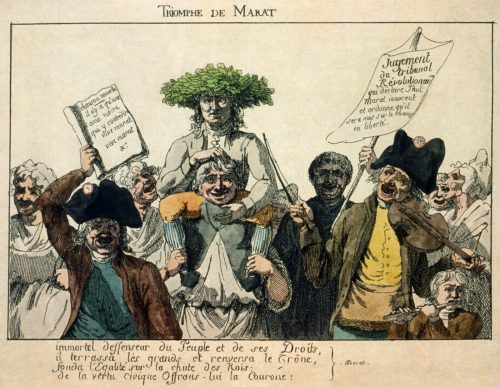

In April 1793, the Girondins fought back against Parisian radicalism, orchestrating the arrest of Jean-Paul Marat, a provocative street journalist turned Montagnard deputy. The following month they established the Commission of Twelve, a special committee tasked with investigating members of the Paris Commune and their alleged attempts to undermine the National Convention. After a brief investigation, the Commission ordered the arrest of several more radicals, including Jacques Hébert.

Calls for a Girondin purge

Having picked a fight with Parisian radicals, the Girondins now faced even greater opposition. The Commune, the Paris sections, the Jacobin club and the sans-culottes all denounced the Girondins as Royalists and Federalists (by this stage, both were anti-revolutionary slurs). Calls soon emerged to remove leading Girondins – or even all Girdondin deputies – from the National Convention.

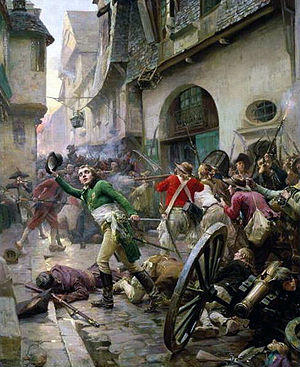

On May 28th, a gathering of around 500 Parisian officials received several petitions and speeches, calling for an insurrection until the National Convention was purged of Girondins. Three days later, on the afternoon of May 31st, a number of protesters entered the Convention building and made demands of a similar nature. This drew supportive speeches from Montagnard deputies but little else.

On June 2nd, around 20,000 Parisians and a contingent of radical National Guardsmen gathered outside the Convention and demanded the expulsion of its Girondinist members. When the Convention president sent a message of protest against this intimidation, National Guard commander François Hanriot replied “Tell your fucking president that he and his Convention can go fuck themselves. If within one hour the 22 [Girondinist deputies] are not delivered, we will blow them all up.”

The radicals triumph

Surrounded and intimidated, the Convention dithered about what to do. Then, Montagnard radicals began to mount the tribune to argue for the expulsion of the Girondin deputies.

Leading this chorus was the wheelchair-bound Georges Couthon, who urged the Convention to abide by the will of the people. The National Guard was not holding the assembly to ransom, Couthon argued; they were its friends and wanted the Convention to choose wisely.

Jean-Paul Marat called for the Girondins to be arrested and detained. Bertrand Barère asked the Girondin deputies to prevent trouble by voluntarily resigning. The prominent Girondin Maximin Isnard refused to do so, declaring that he represented the people of his département and would resign only on their instruction.

Finally, after a standoff and debates lasting several hours, the Convention voted to expel the Girondins. The Girondinist faction had led the revolution since late 1791 – now it had been declared an enemy of the revolution. Some of the Girondin deputies were detained under house arrest. Others fled Paris to the provinces, where they tried to mobilise opposition against the Montagnard-dominated Convention.

In late October 1793, Brissot and 21 of his Girondin followers were tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal and guillotined.

1. The Girondins and Montagnards were two political factions that emerged during the Legislative Assembly and later dominated the National Convention.

2. The Girondins began as followers of the Jacobin orator Jacques Brissot. They were moderate Republicans who supported a revolutionary war and believed the revolution should involve the whole nation, not just Paris.

3. The Montagnards, in contrast, were more influenced by the people of Paris, particularly the sections and the sans-culottes. Their leaders included radicals like Robespierre, Marat, Couthon and Barère.

4. The Girondins and Montagnards frequently differed and bickered over policy. By the spring of 1793, this had developed into a factional war, the Girondins initiating action against radical agitators in Paris.

5. In early June 1793, the Montagnards emerged victorious after the Convention, surrounded by hostile soldiers and sans-culottes, was intimidated into expelling its Girondinist deputies.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Girondins and Montagnards’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/girondins-and-montagnards/

Date published: September 14, 2019

Date updated: November 5, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

The Vendée uprising

The Vendée is a département in western France, located south of the Loire River and on the Atlantic coastline. The Vendée was the epicentre of the largest counter-revolutionary uprising of the French Revolution and its people would pay a heavy price for their resistance. The government’s response was swift and triggered an internecine war in the region. The fight for control of the Vendée lasted three years and produced violence and mass killing that left the Parisian Terror in its wake. Sorokin suggests a conservative death toll of 58,000 but the real loss of life in the Vendée in 1793-96 may well be closer to 200,000.

Reasons for rebellion

In March 1793 provincials in the Vendée, never much interested with the revolution in Paris or its ideas, mobilised and took up arms against the National Convention. There were many reasons for this uprising but chief among them were rising land taxes, the national government’s attacks on the church, the execution of Louis XVI, the expansion of the revolutionary war and the introduction of conscription.

Viewed retrospectively, the Vendée region had all the ingredients for counter-revolutionary sentiment. Located almost 300 miles from Paris, or several days’ travel in the 1700s, it was distant and disconnected from events in the capital. The Vendée was almost entirely rural, with just a few towns and no major cities.

The vast majority of Vendeans were relatively successful peasant farmers; their living conditions were better than those of their counterparts in northern France. The Vendée peasants were not as bitterly affected by the harvest failures and bitter winter of 1788-89. They also enjoyed a comparatively better relationship with the First Estate (unlike elsewhere in France, the noblemen of the Vendée remained on their estates and did not act as absentee landlords).

The citizens of the Vendée were also devoutly religious and dependent on their local parish and clergy.

Indifference to the revolution

The attitude of Vendeans to the French Revolution can be seen in their participation, or rather lack of it, during the Great Fear. The peasants of the Vendée expressed lukewarm support for feudal reform in the cahiers but did not mobilise during the panic of July-August 1789. There were few reports of unrest in the Vendée and no chateaux were burned.

The events of 1790 further alienated the Vendeans from the revolution. Food policies determined in Paris had a detrimental impact in rural areas, where market prices slumped. Yet taxes were not lowered and in some rural areas, they actually increased.

The more pressing issue in the Vendée was the National Constituent Assembly’s attacks on the church. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was widely resisted in the western provinces, where most of the priests refused to take the oath and were backed by their parishioners. The arrival of government officials and constitutional priests in the Vendée in 1791 and 1792 was often met with violent resistance, albeit on a small scale.

Violence breaks out

The Vendée uprising began with small steps but escalated quickly. The trigger points were the execution of Louis XVI (January 1793), then the following months’ National Convention’s Levee des 300,000 hommes, an order demanding 300,000 additional military recruits from the provinces.

This combination of regicide and forced conscription tipped the Vendée’s peasants from localised resistance into full-scale counter-revolution. As the winter snows thawed, small bands of peasants participated in minor but provocative attacks on symbols of the republican government. Département officials, juring priests and Republican sympathisers were insulted, beaten, driven out of the region or murdered.

In mid-March, a local hawker named Jacques Cathelineau organised a group of peasants and seized weapons in Jallais. Cathelineau’s men spent the next three months clearing the region of Republican soldiers and officials.

In Beaupréau, a local peasant militia elected a former cavalry officer, Louis d’Elbée, to lead them. Under his command they captured Chemillé in April. After this victory d’Elbée prevented the slaughter of several hundred Republican prisoners by reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Another significant leader was Jean-Nicolas Stofflet, a gamekeeper and former private in the Swiss Guard, who became a general in the Vendean army.

“From March to June 1793 the movement conquered all. At the outset, the rebels were organised by villages with modest people at their head. Stofflet, an ex-soldier, was a gamekeeper; Cathelineau was a carter. But once the fighting began, the squires of the region were sought to take up the leadership. The speed of events surprised the Convention and early replies were feeble… All of a sudden the Vendée revolt broke out of its isolated bocage landscape.”

Annie Moulin, historian

Early victories

In April 1793, counter-revolutionary forces in the Vendée united to form the Catholic and Royal Army. At its peak, this army would number 80,000. Most were farmers and labourers, some were boys as young as 12 or women disguised as men.

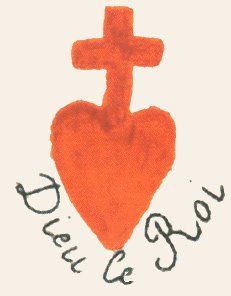

The counter-revolutionaries adopted Dieu et Roi (‘God and King’) as their motto. Their officers wore the white cockade of the Bourbon monarchy while the soldiers wore the Sacre Couer (‘Sacred Heart’). They had little or no training and were poorly equipped, many armed with scythes and pikes rather than muskets.

While the Vendeans lacked the training and discipline to stand against a professional army, the republican armies had themselves been left weakened and disorganised by four years of disruption and desertions. For three months, the royalists of the Vendée swept all before them, capturing significant towns including Beaupréau, Vihiers, Saumur, Angers and Chemillé. They also won control of the Vendée’s most important commercial town, Cholet, and its département capital, Fontenay-le-Comte.

The National Convention had a small number of troops garrisoned in the Vendée so could do little initially.

The tide turns

The tide turned in late June 1793 when the Catholic and Royal Army marched north and laid siege to Nantes, one of France’s largest cities. Their attack was poorly planned and coordinated, and failed after just two days. Jacques Cathelineau, one of the Vendeans’ more competent commanders, was killed during fighting on Bastille Day, 1793.

In October, a 40,000-strong Vendean force marched on a smaller republican army near Cholet but was outmanoeuvred and defeated. Changing tactics, they embarked on a ‘Virée de Galerne’ (‘northern spree’), an attempt to link up with counter-revolutionaries in Brittany and Normandy. In November, the Vendeans marched on the port city of Granville, where they hoped to align with a regiment of English marines. They laid siege to Granville but found no English, only Republicans, so were forced to scatter.

Their numbers now down to fewer than 8,000 men, the Catholic and Royal Army retreated south and captured the city of Savenay. A battle-hardened Republican force of 18,000 arrived the following day and the Vendeans were soon surrounded and defeated.

Retribution

It took several months but the National Convention eventually mobilise a strong military response to the rebellion. What followed in the Vendée was a campaign of recriminations that bordered on genocide.

Under the direction of représentants en mission from Paris, Republican forces began slaughtering Vendean royalists, irrespective of their age, gender or activities. The National Convention, having already sanctioned the Reign of Terror, authorised the formation of 12 army divisions called the Colonnes Infernales (‘Infernal Columns’).

Under the command of General Louis Marie Turreau, these columns swept through the Vendée in the first half of 1794. They crisscrossed the province, tearing down buildings, burning crops and leaving death and destruction in their wake.

The instruments of the Terror were then focussed on the Vendée, where more than 6,000 people – including 400 children – were executed. Some were guillotined but most were shot, stabbed, bayoneted or forcibly drowned. Farms, crops and forests were burned across the Vendée, affecting the innocent as well as the rebels. Action against the potentially rebellious Vendée would continue as late as 1796.

1. The Vendée was a rural province in south-western France. During the spring of 1793, it became the location of the largest counter-revolutionary uprising of the French Revolution.

2. The peasants of the Vendée enjoyed better living conditions, better relations with their nobles and were less troubled by harvest failures. They were also staunch Catholics.

3. Already lukewarm towards the revolution, Vendeans responded angrily to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and other perceived attacks on the church, resisting government officials.

4. The execution of Louis XVI and the introduction of conscription tipped the Vendée into counter-revolution. By April 1793 Vendeans had formed a “Catholic and Royal Army” of 80,000 men and boys.

5. It took the Republicans several months to mobilise but by late 1793 the Vendeans had been defeated. This was followed by a long period of brutality, terror and recriminations against the Vendée that lasted for several years.

The Levee des 300,000 hommes (1793)

Reports on rebels fighting in the Vendée uprising (1793)

Benaben describes recriminations taken against rebels in the Vendée (1793)

General Turreau’s tactics in the Vendée (1794)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Vendée uprising’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/vendee-uprising/

Date published: September 20, 2019

Date updated: November 6, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

Revolutionary war

In 1792, the Legislative Assembly declared revolutionary war against France’s neighbour, Austria. The French Revolutionary Wars would have a profound effect on the new society. They would shape the course of European history, these wars rolling one into the other and lasting a decade – or more than two decades, if one counts the Napoleonic Wars that followed. At various times, the French Revolutionary Wars would involve almost every significant European power. Inside France, the new regime came to be defined by war and the problems, pressures and paranoia that it created.

Reasons for war

The French Revolutionary Wars had many parents: anti-revolutionary paranoia in Europe, agitation and sabre-rattling by French émigrés, foreign concerns about the fate of Louis XVI, the king’s personal agenda, belligerent propaganda and the internal politics of the new regime.

When the French Revolution erupted in 1789, the crowned rulers of Europe watched it with a mixture of scorn, excitation and fear. Some considered the revolution nothing more than a localised insurrection, destined to eventually burn out. Others watched the uprising in France more cautiously, concerned that it might spark a similar uprising in other kingdoms.

The most pivotal figure outside France was Leopold II, brother of Marie Antoinette and newly crowned ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. More progressive than his fellow princes, Leopold admired the Enlightenment and its concepts of constitutional government and natural rights. He was initially sympathetic to the French Revolution, believing the formation of a constitutional monarchy in France might prolong his brother-in-law’s tenure on the throne.

Europe takes action

Leopold II spent his first months on the throne batting away the pleas of French émigrés and trying to avoid a military entanglement in France. He became more interested in France in the summer of 1791, after Louis XVI’s ill-fated attempt to flee Paris left the French king in a more precarious position.

In July 1791, Leopold instigated the Padua Circular, an open letter to the leaders of Prussia, England, Spain, Russia, Sweden and other nations. This circular called for a European military coalition to invade France, halt the revolution and reinstall the monarchy.

The Padua Circular was followed by the Declaration of Pillnitz (August 27th 1791), a joint statement by Leopold and Frederick William II, King of Prussia. The declaration was both a rallying cry to European princes and a warning to the French revolutionaries.

The Declaration of Pillnitz was more bluff than challenge, however, since Leopold still had no desire for war with France, and nor did his European allies. It did not garner much attention in France either, at least not until the rise of the pro-war Girondinist faction.

“According to convention, France went to war in 1792 in a bid to save the Revolution by exporting her principles to the rest of Europe. In reality, such an explanation is at the very least inadequate… nothing was easier for the Brissotins [Girondins] than to cultivate a war they believed would republicanise France, redoubled by the belief that the ancien regime’s armies would flee in terror, that war could be restricted to Austria alone, and that a war would ease France’s numerous economic problems.”

Charles J. Esdaile

The Girondin case for war

Historians have long debated why the Girondins wanted war in 1791-92. The consensus now is that they wanted to militarise the revolution, to provide it with direction and impetus, to distract from domestic economic problems and to consolidate their own power. A war with Austria would, they hoped, ignite French patriotism and reinvigorate revolutionary sentiment. It would also test the loyalty of the king.

Could France win such a war? The Girondin deputies certainly believed so. Austria was weak and her leader was new to the throne and reluctant to fight. Prussia was a rival of Austria, the Girondins assured the Legislative Assembly, so was therefore unlikely to join a coalition. Britain, Russia and Sweden had their own problems and would not entangle themselves in a war against France.

Some Girondins also believed that a revolutionary war would become a “crusade for universal liberty”, as Jacques Brissot put it. “Each soldier will say to his enemy: ‘Brother, I am not going to cut your throat. I am going to free you from the yoke under which you labour. I am going to show you the road to happiness’.”

War declared

These fine words won the day. In March 1792, Leopold II died suddenly and the Austrian throne passed to his 24-year-old son. Seizing the moment, the Girondin ministry began preparing and agitating for war.

On April 20th 1792, Louis XVI attended a session of the Legislative Assembly and sat through speeches calling for a preemptive war. The king then rose and formally declared war against Austria and Emperor Francis II, the nephew of his wife.

It is likely the king wanted war for his own reasons, perhaps hoping the combined might of Austria, Prussia and the émigré forces would drive the revolutionaries from power and restore him to the throne. The Marquis de Lafayette also wanted war; he believed it would correct the revolution, revive the monarchy and restore his own prestige.

Problems in the army

France’s plunge into war was initially disastrous, in part because the nation’s armed forces had been compromised and weakened by the revolution and its ideas. The events of 1789 had fostered poor discipline and insubordination in the ranks of the army. Enlisted soldiers established ‘political committees’ to protect their rights and some grew surly and defiant.

Experienced officers, many already frustrated by the events of the revolution, despised this breakdown of discipline in the ranks. Many officers fled France to become émigrés or simply abandoned the military altogether. Officers who stayed tried to restore discipline with harsh punishments, chiefly detention and floggings, which only made matters worse.

In the spring and summer of 1790, the royal army was beset by a series of mutinies. In August 1790, the garrison in Nancy mutinied, a protest against the National Constituent Assembly’s decision to prohibit political committees in the army. The government sent a 4,500-strong force to crush the mutiny and two dozen of its ringleaders were executed.

France faces invasion

By the time the Legislative Assembly declared war in April 1792, the national army was in a parlous state. France’s leading military commanders – including Lafayette, Count Rochambeau and Marshal Lucker – had little confidence in the army and its capacity for war.

Initial engagements seemed to confirm this. General Charles Dumouriez hastily organised an offensive against Austrian-controlled Belgium in late April. It ended in disaster, with French revolutionary troops fleeing the battlefield and murdering one of their own generals.

By the start of summer, a combined force of Austrians, Prussians, Hessian mercenaries and émigrés was gathering along the Rhine and preparing to invade France. On July 25th the Prussian commander, the Duke of Brunswick, issued his famously provocative manifesto, threatening Paris with destruction.

Four weeks later the Allies crossed the French border, overran Longwy and Verdun, and prepared to march on Paris. These events caused panic in the capital, contributing to the journée of August 10th and the massacre of prisoners in early September.

Fortunes change

Just as Paris and the revolution looked hopelessly lost, Dumouriez instigated a daring but effective manoeuvre to halt the advance. A series of flanking moves, followed by the formation of defensive lines, slowed the Allied progress.

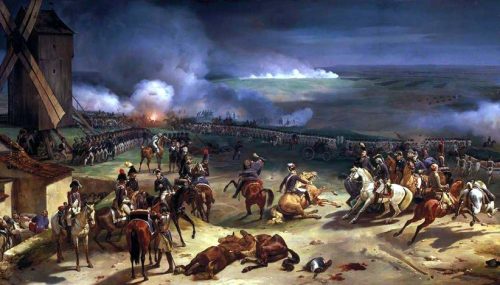

On September 20th 1792, a French force exceeding 30,000 men engaged the invaders at Valmy, halfway between Paris and the border. Amid drenching rain and thick mud, the French outmanoeuvred and outfought Brunswick’s coalition force, which by the following day was in retreat. Within two weeks, the Allied army had withdrawn from French territory and the revolution appeared to have been saved. Dumouriez was hailed as a hero and the new National Convention – which assumed the reins of government on September 20th, the day of the battle at Valmy – moved to abolish the monarchy.

Valmy marked a turning point in French military fortunes but the necessities and problems of war continued to shape both France’s relationships abroad and the course of the revolution at home.

1. War played a significant role in shaping the course of the French Revolution. War with Europe was declared in 1792 and continued for the rest of the revolution and beyond.

2. Within the Legislative Assembly, the Girondins agitated for war for several reasons. They hoped to militarise and energise the revolution, gain public support and consolidate their own power.

3. One of Revolutionary France’s adversaries was Austria. Its king, Leopold II, was initially sympathetic to the revolution and reluctant to initiate a long and costly war with France.

4. The Girondins eventually declared war in April 1792. The first months of the war were disastrous, due to poor discipline and unrest in the army, in part due to the revolution.

5. The French revolutionaries suffered some humiliating defeats but managed to stem the tide in September 1792, defeating the Austrians and Prussians at Valmy and forcing them to retreat from French territory.

Citation information

Title: ‘Revolutionary war’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/revolutionary-war/

Date published: September 24, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

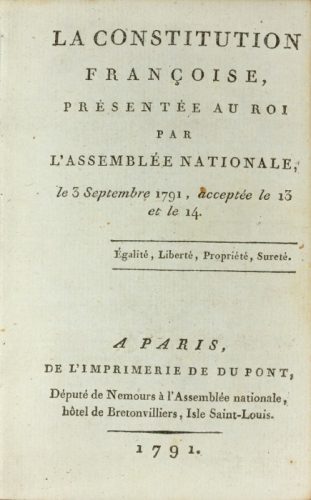

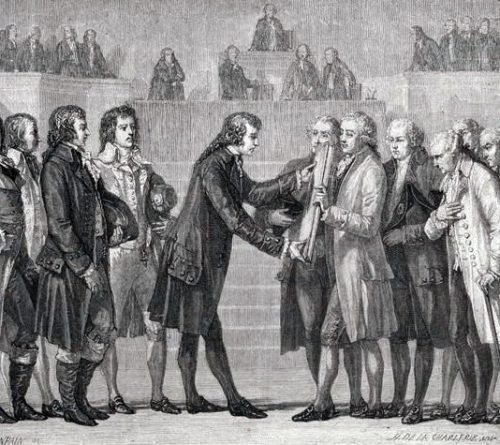

The Constitution of 1791

The Constitution of 1791 was the first of several attempts to create a written constitution for France. Inspired by Enlightenment theories and foreign political systems, it was drafted by a committee of the National Assembly, a group of moderates who hoped to create a better form of royal government rather than something radically new. By the time it was adopted in the autumn of 1791, however, the new constitution was already outdated, overtaken by events of the revolution and growing political radicalism.

Why a constitution?

On June 20th 1789, the newly formed National Assembly assembled in a Versailles tennis court and pledged not to disband until France had a working constitution.

The deputies of the Third Estate believed any reforms to the French state must be outlined in and guaranteed by a written constitution. Such a document would become the fundamental law of the nation, both defining and limiting the power of the government, and protecting the rights of citizens.

Fascination with constitutions and constitutional government was a creature of the Enlightenment. Before the 18th century, monarchical and absolutist governments had acted without any form of written constitution. The structures and power of government were shaped and limited by internal forces and events – if they were limited at all.

The British example

Political theorists looked at systems abroad for examples. Nearby Britain had no written constitution but the power of the British monarchy had been constrained by Britain’s nobility, its parliament, the Civil War (1642-51), the Glorious Revolution (1688) and other factors. Over time, the British system embraced a balance of power between the monarch, the parliament, the aristocracy and the judiciary.

The idea that political power would sort itself out over time was not acceptable to Enlightenment philosophers. Men like John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu and Thomas Paine believed that government must be founded on rational principles and organised in a way that best serves the people.

The best device for ensuring this was a written constitution: a foundational law that defines the structures and powers of government, as well as rules and instructions for its operation.

The American example

The French revolutionaries also had a recent working model of a national constitution. The United States Constitution had been drafted in 1787 and ratified by the American states the following year, in the wake of the American Revolution.

The American constitution embraced and codified several Enlightenment ideas, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau‘s popular sovereignty and Montesquieu’s separation of powers. As the French were deliberating on their own constitution, the Americans were also finalising the inclusion of a bill of rights into theirs.

There was one significant difference between the two systems, however: the American constitution established a republican political system with an elected president as its chief executive, rather than a monarch.

Challenges of a constitutional monarchy

In France, the National Constituent Assembly remained wedded to the idea of a constitutional monarchy. The Assembly wanted to retain the king but to ensure that his executive power was subordinate to both the law and the public good.

This presented the Assembly with two concerns. First, they had to find a constitutional role for the king and determine what political powers, if any, he should retain. Would he remain an active participant in the new system, with the power to appoint ministers, access spending and initiate or block laws? Or would the king simply be a figurehead?

Second, a constitutional monarchy would be entirely dependent on having a king loyal to the constitution. In the months that followed, the king’s lack of interest in constitutional government would cause problems for the new regime.

Drafting a constitution

Preparation and drafting of the constitution began on July 6th 1789, when the National Constituent Assembly appointed a preliminary constitutional committee. This committee was made permanent and expanded to 12 men on July 14th, the day of the Bastille raid, though the two events were unrelated.

Among the members of the constitutional committee were Charles de Talleyrand, Bishop of Autun; the radical Bretonist Isaac le Chapelier; the conservative lawyer Jean-Joseph Mounier; and Emmanuel Sieyès, author of What is the Third Estate?

Almost immediately, the constitutional committee cleaved into two factions. One faction favoured a bicameral (double chamber) legislature and the retention of strong executive powers for the king, including an absolute veto. This group, which included Mounier and the Marquis de Lafayette, was dubbed the Monarchiens or ‘English faction’.

A second group wanted a strong unicameral (single chamber) legislature and a monarchy with very limited power. This group, led by Sieyès and Talleyrand, won the day in the National Constituent Assembly.

The issue of voting rights

By October 1789, the committee was wrestling with questions of franchise: exactly who would have the right to vote to elect the government?

Eventually, the committee decided to separate the population into two classes: ‘active citizens’ (those entitled to vote and stand for office) and ‘passive citizens’ (those who were not). ‘Active citizens’ were males over the age of 25 who paid annual taxes equivalent to at least three days’ wages. This was, in effect, a property qualification on voting rights.

In today’s world, where universal suffrage is the norm, this seems grossly unfair – but property restrictions on voting were quite common in 18th-century Europe. Voting was not a natural right conferred on all: it was a privilege available to those who owned property and paid tax. By way of comparison, England in 1780 was a nation of around eight million people yet only 214,000 people were eligible to vote.

The National Constituent Assembly’s property qualifications were considerably more generous than that. They would have extended voting rights to around 4.3 million Frenchmen. Despite this, radicals in the political clubs and sections demanded that voting rights be granted to all men, regardless of earnings or property.

The king’s new powers

The other feature of the Constitution of 1791 was the revised role of the king. The constitution amended Louis XVI’s title from ‘King of France’ to ‘King of the French’. This implied that the king’s power emanated from the people and the law, not from divine right or national sovereignty. The king was granted a civil list (public finding) of 25 million livres, a reduction of around 20 million livres on his spending before the revolution.

In terms of executive power, the king retained the right to form a cabinet and to select and appoint ministers. A more pressing question was whether he would have the power to block laws passed by the legislature. Again, this was resolved with debate and compromise.

The Monarchiens, most notably Honore Mirabeau, argued for the king to be granted an absolute veto, the executive right to block any legislation. Democratic deputies argued for a more limited veto, and some for no veto at all.

It was eventually decided to give the king a suspensive veto. He could deny assent to bills and withhold this assent for up to five years. After this time, if assent had not been granted by the king, the Assembly could enact the bill without his approval.

“When the Constitution of 1791 was finally adopted, it embodied a fundamental contradiction and a recipe for constitutional impasse. To safeguard national sovereignty from the dangers of representation it permitted the monarch to veto legislative decrees – and hence paralyse the Assembly… As a result of the veto the Constitution of 1791, as Brissot remarked, could only function under a ‘revolutionary king’… Once it appeared, in the spring of 1792, that Louis XVI’s exercise of the veto was frustrating rather than upholding the will of the nation, the monarch and the Constitution itself were under siege.”

Keith M. Baker, historian

The constitution undermined

Even as the constitution was being finalised, any hopes for its success were being overtaken by other events. In June 1791, the king and his family stole away from the Tuileries and fled Paris. They were detained at Varennes the following morning.

The king’s attempt to escape Paris and the revolution brought anti-royalist and republican sentiment to the boil. The National Constituent Assembly tried riding out the storm by claiming the royal family had been abducted and reinstating the king – but the Cordeliers, the radical Jacobins and the sans-culottes of Paris were not buying it.

The Constitution of 1791 was passed in September but had already been fatally compromised by the king’s betrayal. France now had a constitutional monarchy but the monarch, by his actions, had shown no faith in the constitution.

In a conversation with the conservative politician Bertrand de Molleville, Louis XVI suggested that he would bring about change by making the new constitution unworkable:

“I am far from regarding the constitution as a masterpiece. I think it has a great many defects. If I had been permitted to make some observations, some useful changes might have been made. But it is too late for that now. I have sworn to maintain the constitution, wars and all, and I am determined to keep my oath. It is my opinion that that execution of the constitution is the best way of making the people see the changes that are necessary.”

1. The Constitution of 1791 was drafted by the National Constituent Assembly and passed in September 1791. It was France’s first attempt at a written national constitution.

2. The Assembly delegated the task of drafting the constitution to a special constitutional committee. It began in July 1789 by debating the structure the new political system should have.

3. The Assembly eventually concluded that France should be a constitutional monarchy with a unicameral (one house) legislature. Voting rights were restricted to ‘active citizens’, i.e. those who paid a minimum amount of taxation.

4. The constitution retitled Louis XVI as “King of the French”, granted him a reduced civil list, allowed him to select and appoint ministers and gave him a suspensive veto power.

5. The king’s flight to Varennes in June 1791 rendered the Constitution of 1791, and thus the constitutional monarchy, unworkable. It also fuelled a spike in Republican sentiment in Paris.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Constitution of 1791’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/constitution-of-1791/

Date published: September 16, 2019

Date updated: November 11, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

The flight to Varennes

The flight to Varennes is the name given to the royal family’s failed escape from Paris in June 1791. Dissatisfied with the course of the revolution, particularly its attacks on the Catholic church, King Louis XVI acceded to suggestions that it was time to flee the capital. Though well hatched, the plan failed and the royal family were arrested at Varennes, some 150 miles (240 kilometres) from Paris. Their capture was humiliating both for the king and the moderates who supported a constitutional monarchy, a system that now seemed unworkable.

Summary

By the spring of 1791, Louis XVI and his family had been under virtual house arrest at the Tuileries for more than 18 months. Appalled by the growing radicalism of the revolution, particularly its anti-clericalism, the king agreed to abscond from the city. The royal escape plan, hatched by Count Axel von Fersen and supported by Marie Antoinette, was to travel by coach to Montmedy, a fortress near the border with Germany that was garrisoned by royalist troops.

Despite a series of blunders, the royal entourage travelled to within 30 kilometres of its goal, before the king was recognised by a local postmaster. Louis and his family were promptly detained and hustled back to Paris under guard.

The flight to Varennes, though minor in itself, signed the death warrant for bourgeois dreams of a French constitutional monarchy. The king had attempted to flee the revolution and could no longer be trusted. His working alliance with the National Constituent Assembly and his acceptance of the Constitution of 1791 were exposed as fraudulent.

The role of Mirabeau

A number of factors caused Louis XVI to lose whatever faith he had in the revolution. One was the advice of Honore Mirabeau. At the Estates General two years earlier, Mirabeau had seemed an arch-radical, defiantly proclaiming that the National Assembly would only disperse at the point of bayonets.

Mirabeau’s own political vision for France, however, was fundamentally conservative. He favoured a strong monarchy with some of the king’s arbitrary powers checked by a constitution and a legislative assembly. If the monarchy fell, Mirabeau believed, the revolution would collapse into leaderless anarchy. Stripping the king of his powers would alienate him from the revolution and lead it to failure.

To avoid this, Mirabeau became a virtual double agent. In May 1790, he signed a secret deal with the crown, agreeing to work for the king’s benefit in the National Constituent Assembly. Mirabeau’s advisory notes to the king, discovered after his death in April 1791, paint a comprehensive picture of his actions.

By early 1791, Mirabeau was advising Louis to relocate to Rouen or some other provincial capital; once there he could rally support, appeal to the people and lead a national revolution, free of the dark influences in Paris. While he distrusted Mirabeau, the king seemed to accept his advice about retreating from Paris.

Religious motives

Another factor in Louis’ decision to flee Paris was his devout religious faith. The king was appalled by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and its implications for the church in France.