Note: A more detailed account of this topic – along with primary sources, supporting material and online activities – can be found at Alpha History’s dedicated Vietnam War website.

As a 1953 armistice ended fighting in the Korean War, a similar Cold War crisis was unfolding further south in Vietnam. A narrow, mountainous coastal nation sandwiched between China, Laos and Cambodia, Vietnam had long been dominated by foreign imperialists. Medieval Vietnam was ruled by the Chinese, who swallowed it up as a southern province. The Vietnamese forced out the Chinese in the 10th century and secured their independence until French imperialists arrived in the mid-1800s. The French spent more than a half-century milking Vietnam of its natural resources, exploiting its people for cheap labour, repressing local culture and ruthlessly eliminating resistance. In 1940 Vietnam was invaded and occupied by Japanese troops. The French remained as puppet rulers, though their hold on power was weakened. When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, for a time it seemed the Vietnamese might govern their own country. In August that year, a group called the Viet Minh (short for the ‘League for Vietnamese Independence’) launched a bid for power. The following month their leader, Ho Chi Minh, proclaimed a new state: the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh was a Moscow-trained Marxist, however, and the Allies could not countenance him as the leader of an independent Vietnam.

Instead, the Allied powers encouraged the French to return to Vietnam and restore their colonial rule there. This led to confrontation and the outbreak of the First Indochina War (1946-54). With their superior weaponry and military experience, the French quickly drove the Viet Minh out of the cities. French forces surrounded a Viet Minh base north of Hanoi and engaged them in battle – but failed to wipe them out. As the conflict expanded into a full-scale war, France imported tanks, artillery, bombers and almost 200,000 troops. The Viet Minh, meanwhile, adopted guerrilla tactics to offset their lack of weaponry and equipment. Taking advantage of stealth, mobility and surprise, they described their struggle as a war between ‘elephant and tiger’: one combatant was capable of great destruction but large and cumbersome, the other was fast-moving, resourceful and deadly. In May 1954, Viet Minh forces surrounded and defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in northern Vietnam. The siege of Dien Bien Phu proved the decisive battle of the war. French commanders negotiated a surrender and Paris ordered a full-scale withdrawal from Vietnam.

The United States first became involved in Vietnam during World War II. During the war, American officers and agents had worked closely with Vietnamese nationalist groups like the Viet Minh, as both struggled against the Japanese. This co-operation gave Ho Chi Minh some hope the Americans might back the Viet Minh to lead an independent Vietnam after World War II. But intelligence reports hinted at close ties between the Viet Minh, Beijing and Moscow – and in the post-McCarthyist era, the US could not tolerate another Asian communist government. Its preference was for control of Vietnam to return to France, one of America’s Cold War allies. Washington provided military backing as the French struggled to maintain their grip on Vietnam. In the final years of the First Indochina War, the US provided the French with more than $US3 billion of aid and military equipment. The French surrender in 1954 forced the US to find another way to secure Vietnam from communism. At an international conference held in Geneva in mid-1954, it was decided to divide Vietnam at the 17th parallel, creating two transitional states for a temporary period of two years. Elections to reunify Vietnam and finalise its government were scheduled for July 1956.

As had happened in Korea, the two Vietnamese states took different political paths, making any form of peaceful reunification impossible. North Vietnam, under the control of Ho Chi Minh and the communist party Lao Dong, evolved into a one-party socialist state. Ho’s government embraced Chinese-style land reforms, increased food production and achieved considerable industrial growth – but it also engaged in the persecution of landlords, the execution of political opponents and the detention of thousands of Vietnamese in ‘re-education’ camps. Meanwhile, South Vietnam passed into the hands of Ngo Dinh Diem. Despite his lack of experience or prominence, Diem was thrust into the leadership by Washington; the Americans admired Diem’s nationalism, his Christianity and, above all, his hatred of communism. Diem, however, proved no more democratic than the communist regime in North Vietnam. While South Vietnam made some economic advances in the 1950s, it was also stricken by nepotism, corruption, inequality, rigged elections and political murders.

In the late 1950s, North Vietnamese leaders resolved to topple Ngo Dinh Diem and reunify Vietnam by force. They planned to achieve this by infiltrating the South and setting up local communist cells. These agents would act both as guerrilla soldiers and political agitators, conducting a campaign of terrorism against the Diem government and attempting to incite local rebellions. These southern communists became known as the National Liberation Front or NLF; the world knew them as the Viet Cong. The Viet Cong’s anti-government violence, assassinations and bombings steadily increased during the early 1960s. In most cases, the Viet Cong targeted government buildings and installations, South Vietnamese military facilities and businesses and hotels frequented by foreigners, especially Americans and French. Meanwhile, Diem’s political corruption and growing unpopularity were undermining his own regime. In 1963, Diem authorised a campaign against the nation’s majority Buddhist population, a move that placed South Vietnam under the world spotlight. Images of anti-Buddhist violence and Buddhist protestors setting themselves alight in the streets of Saigon led to Washington withdrawing its backing of Diem. In November 1963, he was overthrown and murdered in a military-led coup.

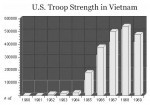

As the situation in South Vietnam become more unstable, the United States stepped up its involvement, sending more military advisors and resources. In August 1964 a skirmish between an American warship and North Vietnamese torpedo boats (the famous ‘Gulf of Tonkin incident‘) provided US president Lyndon Johnson with a pretext for direct military involvement. In early 1965 Johnson authorised an intensive aerial bombardment of North Vietnam, while ordering thousands of American combat troops into Vietnam. This marked the start of the Second Indochina War – known in the West as the Vietnam War. Washington would send more than a half-million troops into Vietnam, purportedly to eradicate the Viet Cong and secure South Vietnam from communism. Unlike the Americans, however, the Viet Cong were under no obligation to engage in major battles or to win the war quickly. For much of the next decade, the Viet Cong played an elusive cat-and-mouse game with the better-equipped, better-trained US troops. They inflicted casualties on American soldiers with ambushes, booby-traps and small-scale battles but, for the most part, avoided a major confrontation.

“Ten years after the end of the war in Vietnam I heard the results of an opinion poll in which people in the US were asked how much they could remember about the war. More than a third could not say which side America had supported, some believed that North Vietnam had been ‘our allies’. This historical amnesia is not accidental but demonstrates the insidious power of the propaganda of the war. The US government line was that the war was essentially a conflict of Vietnamese against Vietnamese, in which Americans became ‘involved’, mistakenly but honourably. This assumption permeated the media coverage during the war and has been the over-riding theme of numerous retrospectives since the war.”

John Pilger, journalist

The turning point in the Vietnam War came in early 1968 when the Viet Cong launched a major offensive in South Vietnam. They did this during Tet, a local holiday when American and South Vietnamese troops were off-guard. The American public, after being told the war was being won and the enemy was exhausted, saw the reality of the situation in Vietnam. The ripple effects of the Tet Offensive were momentous. It fuelled an increase in the US anti-war movement, which peaked in 1969. Many Western journalists declared the Vietnam War a lost cause and called for a peace agreement and American withdrawal. William Westmoreland, the US military commander in Vietnam, was replaced. In March 1968, Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election for the presidency in November. In October 1969, an estimated half-million Americans participated in the National Moratorium against the Vietnam War. The following month, news broke that American GIs had murdered between 350 and 500 civilians – most of them women, children and old men – at My Lai in central Vietnam.

Johnson’s replacement as president was Richard Nixon. Confronted by bad news and growing opposition to the war, Nixon clamoured for a face-saving exit strategy. In 1969 he announced a new policy called ‘Vietnamisation‘: US troops would be gradually withdrawn and replaced by trained South Vietnamese forces. Nixon also secretly ordered the sustained aerial bombing of North Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, an attempt to force Hanoi to the negotiating table. A peace agreement was forged in 1972 when North Vietnam agreed to recognise the South Vietnamese government – provided the US withdraw from the region. Once the Americans had left Vietnam, however, the door was open for the North to launch a full-scale invasion of the South. This came in early 1975, with North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces capturing Saigon in around two months. Abandoned by its American backers, the South Vietnamese government turned tail and fled. Vietnam was reunified under a communist flag and, in 1976, formally became a one-party socialist state.

The loss of Vietnam was a low point for the West generally and the United States specifically. More than 58,000 American servicemen died in Vietnam, along with more than three million Vietnamese. US president John F. Kennedy had promised the world that his country would “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty”. But domestic opposition and America’s withdrawal from Vietnam cast a shadow over this expansive promise. American involvement in Vietnam had been a litany of errors. Washington not only ignored the Geneva Accords, it worked to ensure they would fail. American politicians and propaganda had demonised Ho Chi Minh and eulogised Ngo Dinh Diem when both men deserved neither. American leaders overestimated the political and military capabilities of South Vietnam while underestimating the North Vietnamese. The White House sought military solutions to a political problem and perpetuated a war which, after 1968, was probably unwinnable.

1. Vietnam is a country in south-east Asia, bordering China, Laos and Cambodia. It was colonised by France in the 1800s and then invaded by the Japanese in 1941.

2. The end of World War II and the withdrawal of the Japanese left Vietnam leaderless. In August 1945 Ho Chi Minh and the communist-nationalist Viet Minh claimed power.

3. The US refused to support the Viet Minh and backed the restoration of French rule. Vietnam was temporarily divided in 1954 and evolved into two separate states.

4. South Vietnam was backed by the US but subject to guerrilla attacks from the NLF or Viet Cong. Their terrorism drew the US into landing troops in Vietnam.

5. The Vietnam War spanned a decade, involved more than a half-million US troops and produced a high number of casualties. Among the dead were 58,000 Americans and more than three million Vietnamese.

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018-23. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Vietnam War”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/vietnam-war/.