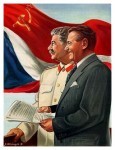

The Prague Spring describes attempts to reform communism in Czechoslovakia during the 1960s. Czechoslovakia was a relatively young nation, formed at the end of World War I. It was invaded by the Nazis at the start of World War II, then liberated by the Soviet Red Army in 1945. But as in other eastern European countries, the Soviet liberation twisted and transformed Czechoslovakia into a Soviet satellite state. By 1948, Czechoslovakia was a one-party state, ruled by a loyal Stalinist and subject to socialist economic policies. Initiated two decades later, the Prague Spring was an attempt to moderate and soften socialism, to bring an end to political oppression and economic austerity. Democracy appeared to take root and flourish behind the Iron Curtain as the government of Alexander Dubcek sought to create “socialism with a human face”. The experiment was short-lived, however, the Soviet Union leading a Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. When the Red Army rolled into Prague in August 1968, it encountered not violent opposition but a people united behind their government and against the iron fist of Soviet communism. Dubcek’s reforms were eventually quashed and his reformist government replaced – but for a short time, the Prague Spring captured the attention of the world.

Sandwiched between East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania, Czechoslovakia was another eastern European country swallowed by the Soviet bloc in the late 1940s. In 1946, the Communist Party took power in Czechoslovakia after an election where it won 38 percent of the votes and 31 percent of the parliamentary seats. Over the next two years, communist policies proved unpopular with many Czechoslovakians. Misuse of the police and armed forces, the nationalisation of industry, plans to collectivise farms and Soviet interference in Czechoslovakian domestic politics all eroded support for the local Communist Party. The communists were expected to lose power in elections scheduled for mid-1948 but these elections were never held. In 1948, with Soviet tanks massed threateningly on the border, Czechoslovakian communists seized complete control of the nation in a bloodless coup. Klement Gottwald, a former cabinet-maker who was loyal to Moscow and the policies of Stalin, became the new president. All other political parties were banned and censorship of the media was imposed. Fourteen former political leaders were given show trials and most of them executed.

As in other Soviet satellite states, the new regime was chiefly focused on industrialisation. By the early 1960s, however, Czechoslovakia’s economy had begun to stagnate. The country was reliant on food imports but its industrial sector was not able to match these with exports. The standard of living deteriorated for ordinary Czechoslovakians; food and consumer goods were both difficult to obtain and very expensive. Intellectuals criticised the centralised economic planning of the communist government – and, remarkably for a Soviet bloc state, the government began to listen. In 1965 it accepted a package of proposed reforms called the New Economic Model. This proposal recommended the adoption of capitalist features, like the removal of price and wage controls. Factory managers and bureaucrats were to be given greater freedom in decision-making so they could respond to resource availability and the needs of the market. This push for reform grew in the spring of 1968 when the local Communist Party issued another manifesto, the Action Plan, calling on Czechoslovakia to adopt its own form of socialism – dubbed “socialism with a human face” – instead of blindly following Soviet policies. Czechoslovakian socialism would be fundamentally democratic, tolerant of debate and different opinions; individual rights and freedoms, such as freedom of speech and the ability to travel abroad, would be protected by law.

The impact of the Czechoslovakian reforms rippled through the Soviet bloc but especially in Moscow. The Soviet Politburo held three days of meetings on August 15-17th to discuss the situation in Czechoslovakia. On the final day, the Politburo released a statement noting that “all political means of assistance” had been exhausted and that the Czechoslovak government was unable to “rebuff rightist and anti-socialist forces”. This document was a de facto ultimatum to Prague: wind back the reforms or a face military occupation. The Czechoslovakian government ignored the ultimatum, prompting a meeting of Warsaw Pact delegates to plan and legitimise a course of military action. They decided that Czechoslovakia was a rogue state and authorised an invasion. On August 21st 1968, around 200,000 Warsaw Pact troops rolled across the borders into Czechoslovakia. The government in Prague, led by Alexander Dubcek, decided not to resist the invasion, so Czechoslovak armed forces were ordered to remain in their barracks.

“Ironically, the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia stabilised the region where the Cold War had begun, and provided a solid basis for detente. After 1968, neither side seriously contemplated going to war in Europe, let alone nuclear war. During the Czechoslovak crisis both sides ‘showed a prudent disposition to underestimate their own strength and over-estimate the strength of the adversary’, concludes one scholar. [Lyndon] Johnson’s inaction and marked aloofness during the Prague Spring, and in response to the Warsaw Pact invasion, also spelled the beginning of the end of US hegemony in the global arena.”

Gunter Bischof, historian

The absence of military opposition surprised the invading Warsaw Pact troops, who had anticipated strong resistance. What alarmed them more was the response of Czechoslovakian citizens. The invading troops were met in the streets by civilians, armed not with weapons but with words, placards and protest. They tore down and replaced street signs so invading tanks could not locate important buildings. They gathered in throngs in main streets, outside public buildings and infrastructure, blocking the way and harassing the Warsaw Pact soldiers. Posters and graffiti reading “Russians go home!” were plastered all over Prague. Locals engaged the invaders in debates, asking why they had invaded Czechoslovakia and inviting them to join the uprising. A group of rebels barricaded themselves inside Prague’s main radio station, broadcasting inspiring messages and criticisms of the Soviet Union. More than 100,000 people filled the street outside the radio station, an attempt to protect it from troops sent to close it down. The radio station was eventually overrun and turned off – but the broadcasters went underground and kept transmitting from there.

Though there was little fighting and fewer than 80 people were killed, the Prague Spring was always destined to fail. Members of the Czechoslovakian government, including Dubcek, were located, arrested and removed to Moscow. Though they were not harmed, Dubcek and his supporters were subjected to intense pressure, intimidation and probably threats, before being returned to Prague a week later. Dubcek told his people that Moscow had authorised him to continue with a program of “moderate reforms” – but within months he had been replaced by Gustav Husak, a communist more loyal to Soviet policies. Between 1969 and 1971, Husak’s regime embarked on what it called ‘normalisation’: essentially a ‘winding back’ of the reforms begun by the Dubcek government. Reformist politicians, bureaucrats and academics were removed from positions of influence; police powers and censorship were reinstalled; centralised economic controls were restored. Husak would remain in power in Czechoslovakia for the duration of the Cold War.

Moscow’s incursion into Czechoslovakia drew widespread international criticism. In the United Nations, a number of countries voted for a resolution condemning the Soviet intervention, though the resolution failed because of the USSR’s veto. The American reaction was comparatively mild, chiefly because the US and its leadership were more focused on the worsening quagmire of the Vietnam War; US-Soviet relations had also been easing and president Lyndon Johnson did not want to antagonise Moscow. Europe’s non-Soviet communists condemned the invasion of Czechoslovakia as an act of imperialism. The leaders of Finland, Romania and Albania all criticised Moscow’s treatment of Prague. There was even a small but visible protest in Moscow itself, though this was quickly suppressed.

1. The Prague Spring was a peaceful but unsuccessful attempt to liberalise and reform socialism in Czechoslovakia. It was suppressed by a Soviet invasion in August 1968.

2. Czechoslovakia was liberated and occupied by Soviet troops after World War II. After a communist coup in 1948, it became a one-party socialist state under a Stalinist leader.

3. Like other Soviet bloc nations, Czechoslovakia adopted centralised economic policies focused on industrial growth. Its economy stagnated, however, leading to shortages and a reliance on imports.

4. In the early 1960s, public opinion and criticism of policy saw the Czech government adopt a series of reforms. Its declared aim was to adopt “socialism with a human face”.

5. Warsaw Pact nations responded with an ultimatum to wind back these reforms. When this ultimatum was ignored, Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia. There was little fighting or violence, however, reformist political leaders were replaced by Moscow and the Prague Spring reforms were wound back under a new pro-Soviet government.

Ludvik Vaculik: the ‘Two-thousand Words Manifesto’ (1968)

Six Soviet nations sign the Bratislava Declaration (1968)

The Soviet ultimatum to end the Prague Spring (1968)

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Prague Spring”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/prague-spring/.