Cold War propaganda sought to promote the virtues and advantages of one political system while criticising or demonising the other. Political propaganda was prevalent throughout the Cold War but reached its heights in the 1950s and 1960s. During this period Pro-American values were promoted in film, television, music, literature and art. This was usually done openly and with little subtlety, particularly in material produced by governments. The 1948 animated feature Make Mine Freedom extolled the advantages and freedoms available to those who live in a capitalist society. Released the following year, Meet King Joe told American workers to be content with their lot, since they had it better than workers anywhere else in the world. As time progressed, the themes and methods in pro-Western propaganda became more subtle. Governments produced less of it themselves, instead relying on film and television studios to incorporate acceptable ideas and values into their product. Many of the radio series, dramas and sit-coms made in America during the 1950s celebrated the distinct advantages of living in a prosperous, capitalist nation. The benefits of things like the nuclear family, school, community, obedience to parents and loyalty to the nation were openly promoted.

In contrast, communism was condemned both as a political ideology and a social and economic system. Every medium, from motion pictures down to children’s comic books, was used to portray an America under the heel of a communist dictatorship. A classic example was the 1962 film Red Nightmare, first made as an instructional device for the armed forces but later released on television. Red Nightmare makes the outlandish claim that entire US cities had been reconstructed in Soviet territory, in order to train communist spies and infiltrators in methods of bringing down American government and society. In the comic book This Godless Communism, an American family finds the US has been taken over by communists, virtually overnight, and renamed the “United Soviet States of America”. As they attempt to find help, they find all their rights and freedoms have been abolished. The father is relocated to a distant lumber mill, the mother to an urban factory and the children to state-run schools and nurseries. In the 1950s the CIA commissioned an animated film version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm – an allegorical account of the Russian Revolution and Soviet government – to serve as propaganda.

Some other examples of Cold War propaganda include:

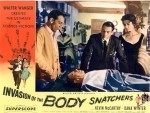

Movies. Motion pictures brought the battle between democracy and communism to the big screen. Many of these films were made in the wake of the HUAC-inspired blacklists, as movie studios and producers strived to appear patriotic and loyal. In Big Jim McLain, John Wayne stars as a House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigator who travels to Hawaii to stamp out communist activity there. Soviet and Western espionage was a common theme, depicted in movies such as The Third Man. Cold War hysteria seeped into the science-fiction genre, in movies such as Red Planet Mars, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Blob. All contained aliens who took the form of shadowy forces hell-bent on taking control of the world by stealth, an obvious metaphor for communist infiltration. Cold War themes were also revived in 1980s films such as Red Dawn (where the US is subject to a joint Soviet-Cuban invasion) and Rocky IV (where an American boxer does battle with a robotic Soviet fighter).

Television. Television was still in its infancy in the 1950s. Most television programs contained music, light entertainment and comedy, so anti-communist themes were represented with more subtlety. American television in the 1950s promoted conservative family values and the virtues of American society, particularly in its situation comedies. Situation comedies like Leave it to Beaver and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet emphasised the importance of education, work, obedience, respect for your parents and the stability and prosperity enjoyed by American families. Cold War espionage was explored in James Bond films and drama series like I Spy and The Man from UNCLE; it was also parodied in the Mel Brooks-created series Get Smart. Even the villains in children’s cartoons like Rocky and Bullwinkle (Boris and Natasha) and Roger Ramjet (Noodles Romanoff) were nothing more than stereotypical European communist agents. Television journalists occasionally influenced public attitudes, such as Edward R. Murrow’s 1954 criticism of Joseph McCarthy, or Walter Cronkite’s 1968 editorial suggesting that the US should look to withdraw from Vietnam.

“The United States and its allies tried to convince their citizens that they lived in the best possible society. It may not have been as free, democratic or egalitarian as the propaganda asserted, but it did boast free markets, limited government, the rule of law, individualism and human rights. A system of selling these beliefs domestically was successfully in place, despite the debunking efforts of its enemies at home and abroad. According to Frederick C. Barghoorn, the Soviet Union attempted to “sap the faith of Americans in their leaders and their institutions”, but failed.”

Daniel Leab, historian

Literature. George Orwell’s 1984 expanded on the Cold War by envisioning a world kept divided and obedient with fears of ‘perpetual war’. The ‘spy novel’ genre was by far the most prevalent in Cold War literature. Ian Fleming’s novels about a British spy, James Bond, were written in the 1950s and were motivated by tensions with the Soviet bloc. In The Spy who Loved Me, Bond does battle with SMERSH, a Soviet counter-espionage agency. John le Carre (a pen-name for David Cornwell, a former employee of British spy agency MI5) penned a number of novels such as The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, set in East Germany. The 1950s and 1960s also saw the production of hundreds of cheap pulp-fiction novels, often with lewd themes or excessive violence. Purgatory of the Conquered showed an America taken over by communist forces; Red Rape told of a Soviet-run operation to capture Western women for the purposes of sexual slavery.

The Arts. Cold War tensions fuelled competition and shaped the content of art forms as diverse as music and ballet. American and Soviet dance companies performed regularly around the world, attempting to demonstrate cultural superiority. This competition led to a dramatic rise in US government funding for the arts. A critical moment came in 1961 when Soviet dancer Rudolf Nureyev defected to the West to perform with Britain’s Royal Ballet; Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev later signed a death warrant for Nureyev, should he ever return to Russia. The US provided funds to allow several orchestras, jazz bands and solo musicians to tour the USSR, in an attempt to demonstrate the artistic advantages of capitalism. The superpowers also engaged in chess competitions to prove whose strategies were more effective.

Sport. Cold War rivalry also carried over into sporting events (see Sport in the Cold War). The 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne were held just days after Soviet forces had crushed a pro-democratic uprising in Hungary, prompting the withdrawal of Holland, Spain and Switzerland from the games. These tensions spilt over into a water polo match between Hungary and the Soviet Union, where players exchanged punches and one left the pool bleeding. The game was called off after the pro-Hungarian crowd threatened to riot. The 1972 Olympic gold medal basketball match between the US and USSR also ended in controversy, with the defeated Americans refusing to accept the silver medal. The 1980 Olympics were held in Moscow and were boycotted by the US, West Germany, Japan and several other nations. The Soviets reciprocated by refusing to attend the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Education. In both hemispheres, education was harnessed for Cold War purposes, to instil into children the political values of each system. Education systems in both the US and USSR received dramatic boosts in funding, particularly in the maths and sciences. Humanities subjects like History and English became steeped in patriotism and political values. In 1952 the American Pledge of Allegiance, widely chanted by schoolchildren, was altered to include the words “under God”. Many American students were also subject to ‘social hygiene’ or ‘mental health’ films in high school. These 10-20 minute single-reel movies focused on what might now be called ‘personal development’: hygiene, manners, respect for others, appropriate behaviour and sexual conduct. Many examples contained an obvious political message or subtext, such as one titled How to Spot a Communist. There were also the ubiquitous instructions and ‘duck and cover’ drills to show what to do in the event of a nuclear attack.

1. Cold War propaganda promoted the virtues and advantages of one system, while criticising or demonising the other. This propaganda was particularly intense during the 1950s and 1960s.

2. Early forms of propaganda, such as animations like Make Mine Freedom and short films like Red Nightmare, contained explicit political messages and warnings.

3. In time, these propaganda messages became more subtle and were integrated into popular culture. American television shows, for example, promoted family values, patriotism and obedience.

4. Cold War culture also focused on the continued activities of spies and secret agents like James Bond, who were well represented in film, television and literature.

5. Cold War propaganda also targeted school children. They were shown lecturing “social hygiene” films and subjected to duck-and-cover civil defence drills, adding to nuclear paranoia.

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Cold War propaganda”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/cold-war-propaganda/.