‘Scar literature’ is a term for writing that appeared in China or from Chinese writers after the death of Mao Zedong. It usually consists of personal accounts that recall the pain and anguish of living in China during the Cultural Revolution. Though scar literature takes the form of personal memoirs rather than history, it still provides some insight into life in China and attitudes towards communism and Mao Zedong.

The ‘Beijing Spring’

The death of Mao Zedong in September 1976 produced public shows of grief and adulation. For many Chinese, however, Mao’s death lifted a great weight from their shoulders. For years, the true mood of the people had been suppressed; Mao’s demise and the rise of more moderate leaders created new opportunities for public expression.

The backlash against the Gang of Four was the first manifestation of the popular will – all four were placed on trial and given lengthy prison sentences. Though Deng Xiaoping refused to openly denounce Mao, as Khrushchev had done to Stalin in Russia, he allowed a period of political and cultural liberalisation, later termed the ‘Beijing Spring’ (1977-78).

During this period, writers, intellectuals and entertainers were permitted to criticise the government and its policies, particularly the Gang of Four and the Cultural Revolution. This sparked a wave of Chinese literature, full of painful accounts of life under Mao. Many of these short stories appeared in official government journals so were passed for publication by state officials.

Cartharsis with limits

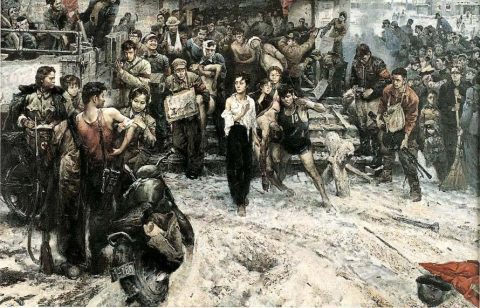

Scar literature was intended to be cathartic, an attempt to ‘cleanse the wounds’ suffered by the people during the 1960s. Many stories contained depressing or horrific accounts of life during the Cultural Revolution: authors told of the persecution, denunciation, beating and even the execution of family members and friends. There were also accounts of life during the Great Leap Forward, particularly the catastrophic famine of the ‘three bitter years’.

Despite the painful content of scar literature, most stories contained very few direct attacks on Mao Zedong or the government (there were still limits on what could be said or written). Nevertheless, many personal stories contained explicit or implied criticism of communist policies. The government began to wind down the publication of scar literature in 1979 but the movement continued abroad, this time in the hands of expatriate Chinese who emigrated or defected and wrote for Western publishers.

There are several examples of these personal memoirs, though some are only semi-autobiographical and tend to lapse into creative writing rather than history. Some examples of scar literature follow, along with a few quotations from each author.

Jung Chang, Wild Swans

Jung Chang was born in Sichuan province, central-western China, in 1952. Her parents were both Communist Party cadres, her father a prominent propagandist, but they lost faith in Mao Zedong after the failures of the Great Leap Forward.

As a teenager, Jung was herself swept up in the fervour of the Cultural Revolution, joining the Red Guards briefly in 1966. Like many party officials, her parents were denounced, publicly humiliated and driven from their comfortable home, while Jung was sent to the countryside to labour.

Jung lost faith in Mao and the CCP, and two years after Mao’s death she relocated to Britain. There she completed a doctorate and published a biography of Madame Sun Yixian. In 1991 Jung Chang published Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (Flamingo, 1991), a biography of her mother and grandmother, as well as a memoir of her own unhappy upbringing. Wild Swans became a bestseller in Western countries, probably the first example of scar literature to receive wide circulation outside China.

“Corruption was so widespread that Jiang Jieshi set up a special organisation to combat it. It was called the ‘Tiger-Beating Squad’ because people compared corrupt officials to fearsome tigers, and it invited citizens to send in their complaints.”

“My father loved Yanan. He found the people there full of enthusiasm, optimism, and purpose. The Party leaders lived simply, like everyone else, in striking contrast with Kuomintang officials. Yanan was no democracy, but compared with where he had come from it seemed to be a paradise of fairness.”

“It was Communist policy [during the Civil War] not to execute anyone who laid down their arms and to treat all prisoners well… The Communists did not run prison camps. They would hold ‘speak bitterness’ meetings for the soldiers, at which they were encouraged to speak up about their hard lives as landless peasants. The revolution, the Communists said, was all about giving them land.”

“The Communist used [the Five Antis] campaign to coax and (more often) cow the capitalists, but in such a way as to maximise their usefulness to the economy. Not many were imprisoned.”

“During this period she [Jung Chang’s mother] had to attend several mass rallies at which ‘enemy agents’ were paraded, denounced, sentenced, handcuffed, and led away to prison – amidst thunderous shouting of slogans and raising of fists by tens of thousands of people.”

“As the years went by [post 1955] and Mao launched one witch hunt after another, the number of victims snowballed, and each victim brought down many others, first and foremost, his or her immediate family.”

“He [Mao] was not worried about the workers or the peasants [during the Hundred Flowers campaign] as he was confident they were grateful to the Communists… He also had a fundamental contempt for them – he did not believe they had the mental capacity to challenge his rule.”

“The whole nation slid into doublespeak [during the Great Leap Forward]. Words became divorced from reality, responsibility and people’s real thoughts. Lies were told with ease because words had lost their meanings – and had ceased to be taken seriously by others.”

“I often had to visit the hospital for my teeth at that time. Whenever I went there I had an attack of nausea at the horrible sight of dozens of people with shiny, almost transparent swollen limbs, as big as barrels.”

“It turned out that the parents of the young girls were selling wind-dried meat. They had abducted and murdered a number of babies and sold them as rabbit meat at exorbitant prices.”

“The famine was worse than anything under the Kuomintang, but it looked different. In Kuomintang days, starvation took place alongside blatant unchecked extravagance.”

“Fear was never absent in the building up of Mao’s cult.”

“One day in 1965, we were suddenly told to go out and start removing all the grass from the lawns. Mao had instructed that grass, flowers, and pets were bourgeois habits and had to be eliminated.”

“To achieve this [loyalty and obedience] he [Mao] needed terror – an intense terror that would block all other considerations and crush all other fears.”

“They [the Red Guards] were also irresponsible, ignorant, and easy to manipulate – and prone to violence.”

“To arouse the young to controlled mob violence, victims were necessary. The most conspicuous targets in any school were the teachers… In practically every school in China, teachers were abused and beaten, sometimes fatally. Some schoolchildren set up prisons in which teachers were tortured.”

“[Families] were beaten with the brass buckles of the Red Guards’ leather belts. They were kicked around and one side of their head was shaved, a humiliating style called the ‘yin and yang head’… In the city centre, some theatre and cinemas were turned into torture chambers.”

“The whole of China [during the Cultural Revolution] was like a prison… By the end of 1968, all university students in China had been summarily ‘graduated’ en masse, without any exam, assigned jobs, and dispersed to every corner of the land [Down to the Countryside]… Mao intended me to spend the rest of my life as a peasant.”

“No matter how much I hated the Cultural Revolution, to doubt Mao still did not enter my mind.”

“The other hallmark of Maoism, it seemed to me, was the rein of ignorance… He [Mao] left behind not only a brutalised nation but also an ugly land with little of its past glory remaining or appreciated.”

Anchee Min, Red Azalea

Anchee Min is a Chinese-American writer and novelist. Born in Shanghai in 1957, Min was sent to work on a collective farm at age 17. After months of debilitating labour, Min was recruited by party officials to star in a propaganda film being produced by Jiang Qing. After Jiang’s arrest and downfall, Min herself endured punishments and demeaning work.

In 1984, Min fled China to the United States, despite speaking no English. Ten years later she published Red Azalea (Berkley Books, 1994), a three-part account of her upbringing in Shanghai, her work on collective farms and her training as an actress. Candid, dramatic and at times frightening, Red Azalea received critical praise and sold very well in Western countries.

“I was an adult since the age of five. That was nothing unusual. The kids I played with all carried their family’s little ones on their backs, tied with a piece of cloth. The little ones played with their own snot while we played hide-and-seek.”

“I led my schoolmates in collecting pennies. We wanted to donate the pennies to the starving children in America.”

“In those years, learning to be revolutionary was everything. The Red Guard showed us how to destroy, how to worship. They jumped off buildings to show their loyalty to Mao.”

“To disobey Mao’s teaching is a crime.”

“We often ran out of food by the end of the month. We would turn into starving animals.”

“In school Mao’s books were our texts.”

“How can I disappoint Chairman Mao, who put his trust in people like us, the working class, the class that was once even lower than the pigs and dogs before Liberation?”

“I want you to be aware of what you are creating, he [a teacher] continued. You are creating an image which will soon dominate China’s ideology. You are creating history, the proletarian’s history. We are giving history back its original face. In a few months, when the movie is all over the country, you will be the idol of revolutionary youths. I want you to memorise Chairman Mao’s teaching, “The power of a good example is infinite”.”

“I looked back when I stepped out of the Peace Park Gate. I saw patrols’ flashlights searching through the bushes. They shouted slogans as warnings: “Beware of reactionary activities!” “Let’s unite and get rid of bourgeois influences!” The park sunk back to the sound of death.”

“Then the news of the century came. It was September 9th 1976. The reddest sun had dropped from the sky of the Middle Kingdom. Mao had passed away. Overnight the country became an ocean of white paper flowers. Mourners beat their heads against the door, on grocery-store counters and on walls. Devastating grief. The official funeral music was broadcast day and night. It made the air sag.”

Li Cunxin, Mao’s Last Dancer

Mao’s Last Dancer (Viking, 2003) was written by Chinese-born Australian ballet dancer Li Cunxin. One of seven children, Li was born into abject poverty in Shandong province in 1961. As an 11-year-old, he was selected to undergo training at the prestigious Beijing Dance Academy.

Much of Mao’s Last Dancer tells of Li’s experiences at the academy, both the rigorous and physically painful ballet training but also the political indoctrination. Li became one of China’s leading dancers. During a visit to the United States in 1981, he defected, remaining there until his emigration to Australia in 1995.

“The commune allocated each family in the village a piece of land.one-twentieth was one-twentieth of an acre … it was so small that it could only be used to grow essential foods such as corn and yams.”

“By the time I was born there was deprivation and disease everywhere. Three years of Mao’s Great leap Forward and three years of bad weather had resulted in one of the greatest famines the world had ever seen. Nearly 30 million people died. And my parents, like everyone else, were desperately fighting for survival.”

“We had no money to take my niang to hospital, and the medicine from the barefoot doctor was cheap and ineffective.”

“About twenty families on their floor shared one bathroom for men and one for women.”

“They [Cunxin’s brothers] would tell me horror stories about the Red Guard, how they burnt and destroyed anything that had a western flavour: books, paintings, artwork – anything. They tore down temples and shrines. Mao wanted communism to have no competition from other religions.”

“The revolutionaries constantly pulled the counterrevolutionaries’ heads back up to humiliate them even more.”

“We all stood up, took our hats off, bowed to Mao’s picture and shouted, ‘Long, long live Chairman Mao! Vice-Chairman Lin, good health, forever good health.”

“Everyone of all ages in China was encouraged to learn from him. Everyone wanted to be a ‘Living Lei Feng’.”

“Throughout the 11 years of my childhood in Qingdao, I had always lived with the harsh reality of not having enough to food to fill our stomachs, of seeing my parents struggle, of witnessing people dying of starvation, of constantly being trapped in that same hopeless, vicious cycle as my forbears. I had been determined to get out of that deep, dark well.”

“The Gang of Four’s theory was that shit attracts flies and that Confucius was the shit and Lin Biao was the fly.”

“But this time, crying for Chairman Mao, it was like a religious experience mixed with a certain fear. I had worshipped Chairman Mao. His name was the first word I had learnt at school. The words of his famous Red Book were embedded in my brain. I would have died for him. And no he was gone.”

With the exception of quotations from other authors, all content on this page is © Alpha History 2018-23. It may not be republished or distributed without permission.

For more information about copyright and reuse, please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha, Jennifer Llewellyn, Sara Taylor and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha et al, “Scar literature“, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/scar-literature/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.