At the outbreak of war with Britain, there were around 500,000 African Americans resident in the 13 colonies, and only about one-tenth were not enslaved. Most would be drawn into the conflict, directly or indirectly, though the reasons for this were diverse and complex.

In some cases, the participation of African Americans was voluntary. Some were inspired by the words of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and the grand talk of liberty, freely offering their services in the faint believe it might bring about their own liberation. Some were freed by their European masters on the proviso they would take up arms against the British (four of the militia at the Battle of Lexington were newly released black slaves). Some Africans were forced into enlistment by their masters, who had either enlisted themselves or offered to send a slave in their place.

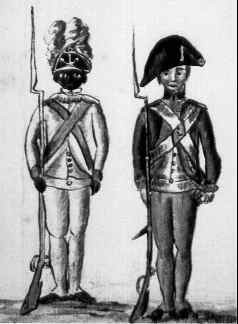

More than 5,000 African Americans would eventually join the Continental Army, some serving in blacks-only regiments but most fighting alongside white soldiers – the first racially integrated American army and the last until the Korean War. Since African Americans in the regular army and the civilian militias were promised their freedom, the war would dramatically increase the numbers of free blacks nationwide (from about 25,000 in 1775 to 60,000 in the 1780s) – though almost all of these were resident in the northern states.

“Although the reasons for using slaves as soldiers were compelling, their employment raised fundamental problems for the plantation system. The arming of slaves contradicted the alleged inferiority of blacks and undermined the racial myths that justified slavery. The American Revolution was, in many ways, an unpropitious [unfavourable] moment to consider arming slaves. The size of the slave population and the proportion of slaves in the larger colonial population was greater than at any time in the history of British America.”

Philip D. Morgan, historian

The role of native Americans during the war was less clear. As a general rule, most native groups supported the British because the Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 had offered them some semblance of native title. An American victory would mean westward expansion from the 13 colonies and further conflict.

This was not always the case. The Iroquois Confederacy, a league or alliance of six different native tribes, could not form a consensus on which side to support, causing a split. The Cherokee tribe also divided into pro- and anti-American factions. More than 2,000 Iroquois warriors fought eagerly with the British, conducting damaging raids on American settlements in the north-east. In 1779 Washington, unable to protect the frontier and fed up with the Iroquois, ordered a scorched earth policy against them, issuing the following orders to General John Sullivan:

“The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

The so-called Sullivan Expedition wiped out approximately 40 Iroquois villages, killing or driving off the population, destroying buildings, burning crops and orchards. The natives gave Washington the title ‘Caunotaucarius’, meaning ‘destroyer of towns’ – however the general himself considered the expedition to be unsuccessful and Sullivan later resigned his commission. The Iroquois did continue their raids on American positions, though they became less frequent.

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History 2019. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.