In June 1768, British authorities commandeered and took ownership of the Liberty, a ship owned by affluent Boston merchant John Hancock. This action followed allegations that Hancock’s ship was being used to smuggle wine. News of the seizure of Liberty sparked rioting by a local mob and some violence and intimidation of customs officials and local Loyalists. The incident not only inflamed tensions in Boston but led the deployment of British troops to the city, a decision that contributed to the Boston Massacre.

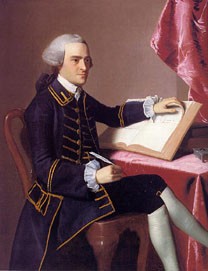

John Hancock

The figure at the centre of the incident was John Hancock. Born in Braintree, Massachusetts, Hancock had been raised by his uncle, Thomas, a successful importer of British goods. After completing a degree at Harvard in 1754, John returned to the family business, the House of Hancock, completing a two-year stint working in London. He inherited this business after his uncle’s death in 1764.

By the mid 1760s, John Hancock was a member of the Boston elite and one of the wealthiest men in British North America. Understanding the importance of political connections in a successful business, Hancock involved himself in public activities, and by 1765 was a selectman in Boston’s municipal government. Hancock was also known for his foppery and extravagance, constructing one of Boston’s grandest houses and wearing the finest imported clothes.

Hancock had no moral qualms about smuggling: he saw British customs duties simply as an obstacle to be avoided. It was a view he inherited from his uncle, whose company had made considerable amounts dodging the 1733 Molasses Act and selling cheap smuggled molasses to local rum distillers. John Hancock continued the tradition and was not deterred by either the Sugar Act or the Townshend laws.

Historian Stephan Thernstrom says of Hancock:

“Owing to the lightness of his character, excessive vanity and his love of popularity, unballasted by either moral depth or intellectual ability, Hancock’s motives for joining the patriot party are difficult to appraise correctly or even perhaps fairly. But there was no question of patriotism in much of his smuggling. That was for profit.”

A crackdown on smuggling

Hancock was certainly not the only merchant engaged in smuggling. The practice was rife in all colonial ports and continued up to the first shots of revolution. It has been estimated that before 1767, the British collected around £2,000 in duties each year, but the costs of collection were three or four times that figure.

The usual practice was for customs collectors was to ask the ship’s captain how much dutiable cargo he was carrying. Many captains would declare a small portion and unload the rest free from any duty. It was a blind-eye arrangement that suited everyone: the cargo importer avoided most of the duty while customs officials avoided difficulty and conflict. Some would receive a bribe in cash or goods that offset their meagre pay.

Before 1767, these collectors had been overseen by customs commissioners – usually poorly paid local agents who were themselves susceptible to intimidation or bribery. After the passing of the Townshend acts, a new body called the Board of Customs Commissioners was established in Boston and instead staffed with five career bureaucrats.

In the first months of 1768, the nature of customs collections changed markedly. The new Board of Commissioners would allow some of the older practices to continue and then, without warning, impose a rigorous crackdown. Without notice, vessels were halted, inspected and searched. Ships and cargoes found in breach of the law may be seized and sold off. This all-or-nothing approach proved far more lucrative than routinely scrounging for duties.

The Liberty affair

The Liberty was a sloop, or small cargo ship. It had just recently been acquired by Hancock’s business, which was using it to ship wine and smallgoods from Europe to Boston for resale.

On May 9th 1768, the Liberty docked in Boston Harbour loaded with more than 100 casks of Madeira wine. Soon after, it was visited by a customs official, who insisted on inspecting the vessel. Incensed, the ship’s captain seized the man and locked him in the brig until most of the cargo had been unloaded and moved on.

The following morning, the inspector was released while the ship’s captain logged a small amount of the wine with the customs house. The incident seemed to be at an end but within a month, the Board of Commissioners had learned of the Liberty, the actions of its crew and its undeclared cargo.

On June 10th, marines from HMS Romney, a 50-gun British warship tasked with policing the Navigation Acts in Boston Harbour, were sent to take possession of the Liberty. They rowed out to Hancock’s ship, expelled the crew and marked it as being the property of the King. They then set about roping it to the Romney to prevent its recovery.

The Boston mob responds

Tensions in Boston were already running high due to the zealous conduct of customers commissioners, their seizure of other ships and cargo, and the impressment of local men into naval service on the Romney. Word of the seizure of Liberty soon spread and it proved a tipping point.

An incensed mob of several hundred men soon appeared on the docks. There, two customs officials were beaten senseless and their boat was stolen and burned.

The crowd then moved on to the homes of other officials, who had windows broken and property destroyed. Over the next two days more than 60 customs officials and Loyalists, fearing for their lives, took refugee either in Castle William, the local fort, or on government ships moored in the harbour.

At this point, the commissioners sought to calm the situation by negotiating a compromise. Hancock offered to pay a suitable bond and submit to an investigation, provided the Liberty was returned. Boston’s radicals, most notably Samuel Adams, talked Hancock out of this deal, preferring to sustain local outrage over the incident.

The British kept Hancock’s ship, renamed it HMS Liberty and tasked it with locating smugglers in New England ports.

Aftermath

Following the Liberty incident, a meeting of local Sons of Liberty decided to lobby the Massachusetts governor, Francis Bernard, to request the withdrawal of HMS Romney and an end of British impressment in the city. Bernard promised to do what he could, though by now the situation was out of his control.

John Hancock later received several writs for costs and unpaid duties stemming from the Liberty affair. He was defended at trial by John Adams, who succeeded in having the charges dismissed. Hancock had been a critic of British revenue policies previously but the Liberty incident hardened his anti-British position. It also boosted his profile among Boston’s Sons of Liberty.

More significantly, the Liberty affair and the mob violence that followed suggested to British parliamentarians that Boston was an unruly, even lawless place, desperately in need of a stronger military presence. This led to an increase in British troops in the city that precipitated the Boston Massacre two years later.

1. The Liberty affair was an incident in Boston in May and June 1768. It involved a ship belonging to wealthy merchant John Hancock that had been engaged in smuggling.

2. The passing of the Townshend acts led to firmer policing and crackdowns on smuggling, with trading ships routinely boarded, searched and occasionally, seized.

3. When Hancock’s Liberty was suspected of smuggling large amounts of wine, a British naval vessel was ordered to seize and commandeer it.

4. This prompted an angry response from a local mob, who attacked and menaced officials and Loyalists. The British retained ownership of Liberty after Hancock refused a compromise deal.

5. The incident increased tensions in Boston, increased John Hancock’s profile the among revolutionaries, and led to Parliament increasing the number of British troops in the city.

Citation information

Title: ‘The seizure of Liberty‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/americanrevolution/seizure-of-liberty

Date published: July 16, 2019

Date updated: November 22, 2023

Date accessed: April 20, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.