George Washington (1732-1799) was an American military commander, politician, statesman and the best known leader of the American Revolution. During his lifetime Washington served as an officer in the Virginian colonial militia, a member of the colonial gentry, a delegate to the Virginian House of Burgesses, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, chairman of the Philadelphia constitutional convention and the first president of the United States. It is not an exaggeration to suggest that without George Washington, the American Revolution may have taken an entirely different route. His contribution seems even more remarkable, given that as late as 1762 Washington was seeking a commission in the British regular army. Had London not rejected his overtures, Washington may well have ended up fighting against the Continental Army, rather than commanding it.

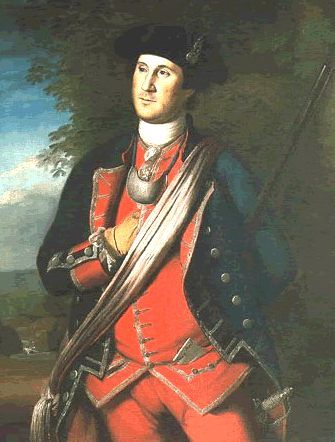

George Washington was born in Virginia in 1732, the third son of a prosperous tobacco planter. His two older brothers were educated in England, however the death of his father in 1743 meant Washington was denied this opportunity. He instead trained as a surveyor, marking the start of a lifelong interest in land and speculation. By adulthood Washington was a striking figure, possessed of a booming voice and imposing height (at six foot two inches or 188 centimetres he was significantly taller than most colonial American men). In 1753, with Anglo-French frontier tensions building, Washington was commissioned in the Virginian militia and sent to protect British wilderness settlements. Despite carrying instructions to avoid confrontation, Washington ambushed a French patrol and triggered a retaliatory attack against the British-held Fort Necessity. His men were surrounded and captured, forcing Washington to sign an embarrassing admission of liability. This early military escapade marked a flashpoint in the French and Indian War.

Washington served the duration of the war then returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon. There he became a successful tobacco planter, while experimenting with wheat, hemp and rye (he used the latter to produce and sell whiskey). Mount Vernon was tended by up to 300 African-American slaves, half of them owned by Washington. Contemporary accounts suggest Washington treated slaves better than other owners, though he had low regard for their intellectual capacity. In 1758 Washington was elected to the Virginia legislature and the following year married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow whose fortune passed to her new husband.

Like many of the colonial gentry, Washington had mixed feelings about England. He was proudly loyal to the king and parliament and a great admirer of British imperial, military and naval strength. But Washington was privately frustrated by his commercial dealings with English companies, which gave him poor prices for exports yet charged exorbitantly for manufactured goods. Washington also claimed substantial tracts of land in the western territories in 1763, only to see these claims thwarted by the royal proclamation later that year. Washington’s response to the 1765 Stamp Act was lukewarm. He said little about it in public or in the legislature; he chose not to attend the debates which led to the Virginia Resolves, claiming to have important planting at Mount Vernon. Privately Washington seemed to believe the Stamp Act was just a policy error that would be corrected in due course.

“In the sixteen years since Washington’s first election to the Burgesses [Virginia assembly] he had displayed anything but an overwhelming interest in the issues that concerned legislators. He was repeatedly re-elected, but his legislative performance was lackluster at best. In some years he had not bothered to attend even a single assembly session. His disinterest should not come as a surprise. He had commenced his legislative service without ever having enunciated his views on any public issue, save for those that affected him directly… What chiefly interested him was amassing and protecting his personal fortune.”

John E. Ferling, historian

Washington’s position was hardened by London’s continued attempts to extract revenue from her American colonies. The Townshend duties stirred the Virginian to greater action – not least because they affected his own business interests. In 1769 Washington sat on a committee that encouraged a continent-wide boycott of English imports; the committee’s objective was to deny trade to British companies “till ruin stares them in the face”. By now, Washington was openly describing British policies as a deliberate attempt to drive the colonies to subservience. “Our lordly masters in Great Britain”, Washington wrote in 1769, “will only be satisfied with the deprivation of American freedom.” Washington was one of the first to suggest the possibility of taking up arms, albeit as a last resort. Like most moderates Washington did not support the destruction of private property at the centre of the Boston Tea Party; he even suggested that Massachusetts should provide compensation. But he deplored the Coercive Acts, which he called “despotic measures”, an “invasion of our rights and privileges”, part of a “regular systematic plan [to] fix the shackles of slavery upon us”.

By the end of 1774, Washington the critic of British policy had become Washington the revolutionary. He led the passing of anti-British resolves in his native county of Fairfax, then won nomination to the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He took a back seat in the debates but supported the Congress’ motions for colonial association and non-importation. Washington’s moment came during the second Continental Congress, a month after the fighting at Lexington and Concord. Washington attended Congress in his Virginia colonel’s uniform, as if to signal his readiness for war and to remind other delegates of his military experience. Washington was appointed commander-in-chief of the newly-formed Continental Army. His appointment was partly political, a move to bind the populous and wealthy Virginia to the war.

After receiving his commission Washington joined the Continental Army outside Boston. His first inspection revealed the enormity of the challenge confronting him. Washington’s ‘army’ ranged from part time militiamen to angry farmers; they were eager to fight but lacked military discipline, training, understanding of command structures or procedures. Most Continental officers had been elected by the men and were poorly trained or unfit to lead. The Continentals lacked stores, weapons, munitions, tents, blankets and other necessities of war. It would take months for Washington to shape these men – whom he initially referred to as “dirty nasty people” – into anything resembling a professional military force. Assuming the duties of more junior officers, Washington implemented military routines, posted daily orders, organised drills, coached his officers and trained the men. An admirer of the British army and its discipline, Washington was not averse to using corporal punishment to impose order. He authorised his officers to employ flogging for a wide range of offences, ordering that afterwards the backs of flogged men be “well washed with salt and water”.

Washington was also a determined advocate for his men and conscious of their needs, particularly when dealing with the Continental Congress, state assemblies or wealthy donors. For much of the war Washington lobbied for more men with longer enlistments, more foreign volunteers and mercenaries, more weapons and munitions, more money, food, livestock, wagons, uniforms, boots and blankets. He hated this because it distracted him from the true business of military command, but he recognised its importance. These heavy burdens and frustrations, coupled with a string of military defeats in 1776, took a huge psychological toll on the general. Yet though Washington could be moody and short-tempered in private, he was careful to avoid displays of anger, emotion or exasperation, both in public and in correspondence, because he knew the eyes of America were upon him.

© Alpha History 2015. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Steve Thompson and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

S. Thompson & J. Llewellyn, “George Washington”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/americanrevolution/george-washington/.