The United States may have emerged from the Revolutionary War victorious but economically, it was in dire straits. The strain of a long and costly war had exhausted both state treasuries and private wealth. Both the new national government ($54 million) and the states ($21 million) were left with massive war debts, chiefly to foreign powers such as France. There was a shortage of specie or ‘hard currency’, mainly because the Currency Act of 1764 had depleted America’s reserves of gold and silver in the years before the revolution.

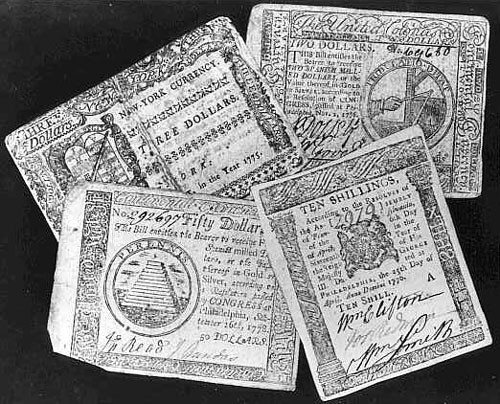

American governments had attempted to fund the war through excessive printing runs of paper money. The states had printed $209 million of notes, Congress $241 million, and these ‘bills of promise’ had begun to lose their value almost as soon as they hit the streets. By 1781, a paper Continental dollar was worth about five per cent of a silver dollar, giving rise to the idiom ‘not worth a Continental’. And America’s balance of trade was extremely negative, meaning she imported significantly more than she exported, exacerbating the problems mentioned above.

There was also a collapse in public credit, as ordinary Americans, often returned Continental soldiers who had been unpaid or underpaid, borrowed heavily from urban creditors to establish farms or homes – and were unable to meet repayments due to the slumping agricultural market of the mid-1780s.

Some state assemblies responded to this suffering, tension, unrest and (by 1786) uprisings by easing taxation and cancelling or reducing private debt. Private creditors saw their wealth evaporate thanks to irresponsible state government, fuelling demands for a reform of the Articles of Confederation.

“Surveying his native Virginia, James Madison observed in mid-1785 that ‘the trade of the country is in deplorable condition’ with prices for tobacco – a major export – slipping 50 per cent. Wholesale prices for farm products in Philadelphia in 1786 dropped by nearly two-thirds from 1784 levels… One recent estimate calculated the economy declined by 41 per cent between 1774 and 1790.”

Ballard C. Campbell, historian

Individuals and groups favouring strong national government and responsible economic management began to muster as America slipped into deep recession in 1784-5. Whether the Articles of Confederation actually caused this recession, or just made a political response more difficult than it should have been, is a point of some dispute amongst historians.

The consensus is that the Articles of Confederation failed and were not capable of providing effective government for the new nation. Some like H. A. Scott Trask, however, believe that the Articles are unfairly denigrated, and that the real economic culprits – debts, inflation, shortage of specie and imbalance of trade – were painful but temporary after-effects of a long war.

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History 2019. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.